Giovanni Boccaccio! He is inextricably connected with the Renaissance, just as Petrarch is. Boccaccio was a man of the Renaissance in almost every sense.

Born to a Tuscan merchant Boccaccio di Chellino, Giovanni came into the world in the summer of 1313. The exact date and place of Giovanni’s birth are unknown, but, according to some contemporary sources, his date of birth might be the 16th of June 1313. His mother is unknown; she was probably French and not married to his father. He seems to have been born in Certaldo or in Florence, where he grew up in the home of his father and his stepmother.

In early childhood, Boccaccio felt that his destiny was to compose verses. However, the older Boccaccio was not well disposed towards his son’s literary desires, so he sent his teenaged son to the Kingdom of Naples to work in an office of the Bardi bankers, to whom the local royal court owed a lot of money. Hard work and talent are like teenage siblings, and even though Giovanni had a talent in writing, he must have worked a great deal to develop his talent and style.

Boccaccio wrote of his childhood and of his early years in Naples:

“I remember that, before having completed my seventh year, a desire was born in me to compose verse, and I wrote certain poetic fancies… It happened that I am not a merchant, I have not turned out to be a canonist, and have not become a distinguished poet.”

As he disliked his occupation, Boccaccio convinced his father to let him study law at the Studium (now it is the University of Naples), where he studied canon law for the next several years. Boccaccio gained access to the aristocratic society through his parent’s contacts. At the court of King Robert of Anjou who ruled Naples at the time, the young man engaged in captivating discussions with philosophers, scientists, men of letters, and artists. It was when he learned mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy, as well as mythology. Although Giovanni had studied Latin in childhood, only during his life in Naples he commenced learning the Greek language and history of ancient Greece. In Naples, the adult Boccaccio morphed into a true writer.

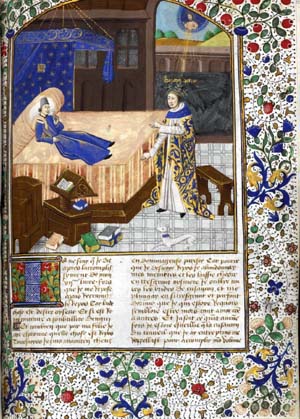

A Vision of Fiammetta by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1878

Cupid’s dart struck the young man in Naples and altered the fabrics of his creative life. In 1336, Boccaccio fell in ardent love with the young noblewoman who was called Fiammetta in his works. According to some sources, his muse was Maria d’Aquino, the illegitimate daughter of King Robert and the Count of Aquino’s wife, but this cannot be proved. For a while, Fiammetta seems to have reciprocated Boccaccio’s affections: he was so smitten with her that she was his inspiration for all his youthful literary creations in Italian, including his Il filocolo (c. 1336, “The Love Afflicted”).

Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta

After the bankruptcy of the Bardi, Boccaccio’s father became poor and recalled his son from Naples in 1340. Giovanni was unhappy with his return to Florence, and little is known about this period of his life. He wrote L’Ameto (c. 1341 or 1342), which is a pastoral romance in prose and terza rima (a rhyming verse stanza form that consists of an interlocking three-

In 1348, Boccaccio was in Florence, which was severely hit by the Black Death (it peaked in Europe from 1347 to 1351). As a witness of how the pestilence destroyed about three-quarters of the city’s population, he described that in the Decameron, which he completed by 1353.

The book was structured as a frame story containing 100 tales told by a group of 7 women and 3 men, sheltering in a secluded villa outside Florence to avoid the plague. To pass the evenings, each of them tells a story each night, except for one day per week for chores, and the holy days. Tragic and comic views of life alternate with tales of short-lived happiness, erotic affairs, and tragic love. The sharp contrast to the moral and social chaos of plague-ravaged Florence is the liveliness of the moments spent by the characters entirely engaged in witty conversations. Some tales are of how women play tricks on men and of how people play them on each other. Rightly regarded as Boccaccio’s great masterpiece, the Decameron was the perfect example of Italian classical prose, and its influence on Renaissance literature was colossal.

A tale from The Decameron, by John William Waterhouse

But although the Decameron is the finest example of early Renaissance prose, its author firmly believed in the ideas of the Middle Ages. For example, in this work, Boccaccio claimed that to be truly noble, man must accept life as it is, without embroidering it with fantasy and harboring bitterness or malice. It was implied that people had to accept their social status and exist within their own class, whether one was a peasant, a serf, a noble, a lord, a knight, or a king. These are traditional beliefs of a medieval person, which were cultivated by the Church.

This work was Boccaccio’s final effort in literature and one of his last works in the Italian language. In his later years, his mindset and works were highly influenced by his friendship with Francesco Petrarca (commonly anglicized as Petrarch), with whom he had first met in Florence in 1350; later he met with Petrarch in Venice in 1365 and in Padua in 1368. These two illustrious men maintained constant correspondence. Boccaccio’s relationship with Petrarch brought about a dramatic change in his literary activity, and he began interacting with various humanists.

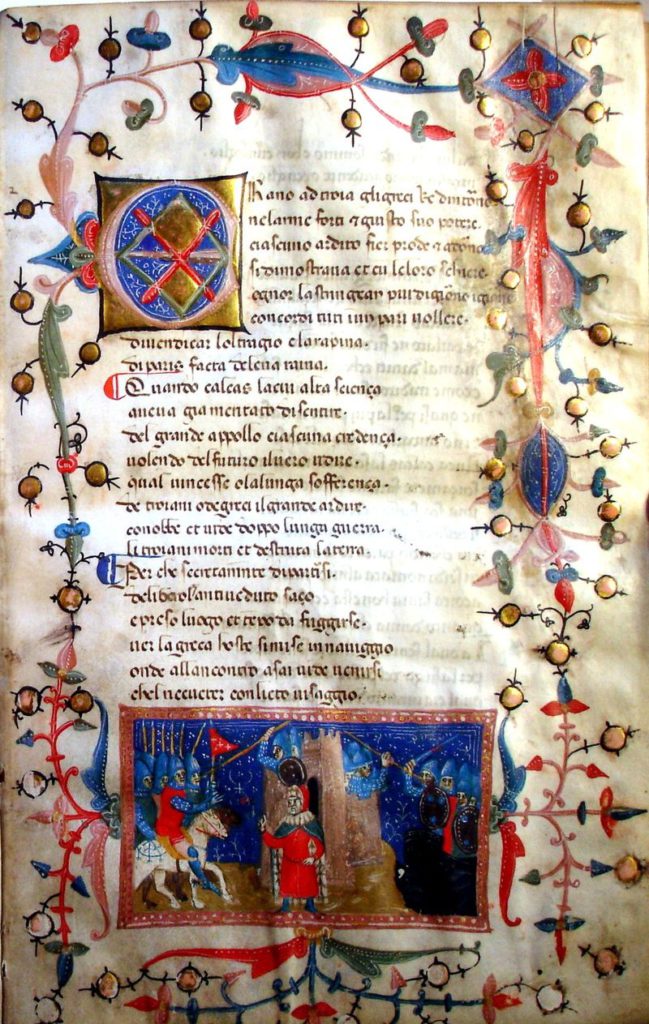

A page with miniature of Boccaccio’s vision of Petrarch

From 1360 to 1362, Leonzio Pilato (a scholar who promoted Greek studies in Europe) stayed at Boccaccio’s home in Florence. It is through this connection with Petrarch and Boccaccio that the previously unknown Greek culture became a focus of studies for many European humanists in centuries to come. Pilato produced for Boccaccio the rough Latin translation of Homer’s works, which was subsequently sent to Petrarch.

Giovanni was fervently interested in the recovery of important Latin classical texts such as Petronius, Varro, Seneca, Ovid, and, above all, Tacitus. In Boccacio’s Genealogia deorum gentilium (c. 1360, “On the Genealogy of the Gods of the Gentiles”), which was an excellent work on the pantheons of ancient Greece and Rome and was written in Latin prose, Boccaccio claimed that he had reconstituted the linguistic unity of the Greco-Roman antiquity.

Despite his interest in humanism, Boccaccio did not neglect Italian poetry. He was fond of Dante and wrote in Dante’s memory and honor the famous His Vita di Dante Alighieri (c. 1357, “Little Tractate in Praise of Dante”). His late sensual poetry was no longer full of chivalry and idealization of love, and some of his verses may be considered bitterly misogynistic such as Corbaccio (c. 1355, “The Crow”), which was caused by his unfortunate personal life. The older Boccaccio wrote both poetry and prose, but they all were darker than his early works.

For the rest of his life, Giovanni struggled to maintain financial stability. While his health was rapidly deteriorating, Boccaccio was forced to live almost in destitution. His lifestyle was also becoming increasingly austere, and perhaps he was totally devastated psychologically when one day, he resolved to have his magnificent library burned. Fortunately, Petrarch dissuaded him from doing so, and upon Boccaccio’s death on the 21th of December 1375, his whole collection was given to the monastery of Santo Spirito in Florence, where it still resides.

The life of Boccaccio was a fabulous, yet sad, path of a God-gifted man. Giovanni’s art was characterized by the culture of two ages – the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, just as Petrarch’s was. Boccaccio was both an admirer of the classics and an accomplished writer, who, nevertheless, remained a medieval man in his philosophical and theological views.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2019 Olivia Longueville