On the 2nd of August 1100, King William II of England, the second surviving son of William the Conqueror and his wife, Matilda of Flanders, passed away. Their two other surviving sons were Robert II Curthose, and Henry (the future King Henry I of England). William I was known as William Rufus, with Rufus meaning in Latin ‘the Red’, because of his ruddy appearance or his red flaming hair. He ruled England for only 13 years – from 1087 until 1100. Why was William’s reign rather short?

After the passing of William the Conqueror, Robert Curthose became Duke of Normandy, while England became the domain of William Rufus. After William II’s coronation on the 26th of September 1087, the new monarch faced a rebellion in favor of Robert, led by their uncle Odo, Earl of Kent and Bishop of Bayeux. The uprising was squashed largely thanks to the aid of English levies, and a grateful William promised them less taxation and milder forest laws, but the king did not keep his promises. Later, in 1091, William launched an attack on his elder brother’s holdings in Normandy, and it all ended with the Treaty of Rouen, according to which Robert allowed him to keep the conquered lands in exchange for help to regain the county of Maine. William, however, soon forgot about the treaty.

Lanfranc, who served as Archbishop of Canterbury following England’s Conquest by William the Conqueror, died in 1089. Lanfranc was loyal to the Conqueror and upon his death, secured the succession for William Rufus despite the displeasure of the Anglo-Norman baronage. William, who seemed to be either not pious or irreligious at all, was not in a hurry to ensure that the new Archbishop of Canterbury was appointed. As a result, the place was kept vacant, and the Church became leaderless, which was exploited by Ranulf Flambard, a Norman Bishop of Durham and a powerful minister. Ranulf administered a significant number of the vacant ecclesiastical offices, managed 16 bishoprics, and obtained the rich see of Durham for himself in 1099.

In 1093, William was so seriously ill that he thought he was dying. In fear, the king urgently selected Anselm, who was another Norman-Italian great theologian of the time, to be the Archbishop of Canterbury. However, the absence of the Church leader created animosity towards William from his barons. Another problem was that Anselm was a stronger supporter of the Gregorian reforms (a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the papal curia c. 1050–80) in the Church than Lanfranc. William and Anselm quarreled on a range of ecclesiastical issues and other religious issues, in the course of which the monarch chastised Anselm and is known to have said,

“Yesterday I hated him with great hatred, today I hate him with yet greater hatred and he can be certain that tomorrow and thereafter I shall hate him continually with ever fiercer and more bitter hatred.”

In 1095, William convened a Council at Rockingham to bring Anselm to heel. In October 1097, Anselm was exiled from England and went directly to the Pope, asking him for help. However, the new Pope Urban II had a serious disagreement with Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, who supported an antipope. In order not to create another enemy the Pope concluded a concordat with William II, in which the king recognized Urban as pope, while Urban sanctioned the Anglo-Norman ecclesiastical status quo. In Anselm’s absence, William collected the revenues of the archbishop of Canterbury until the end of his reign, which did not add popularity to Rufus.

Austin Lane Poole, a 19 and 20-th century British mediaevalist, wrote about William II:

“From a moral standpoint… probably the worst king that has occupied the throne of England.”

In 1096, Robert II Curthose decided to go on Crusade, but he did not have enough money to finance his expedition. Pious and zealous to participate in the fight in the Holy Land, Robert offered William to pledge his duchy in exchange for 100,000 marks. A joyful William eagerly consented and raised money in England, which allowed Robert to form a large and well-equipped army. After Robert had left on the First Crusade, William seized control of Normandy and restored order there, and from his new positions he attacked Maine and the French Vexin.

in a 19th-century painting by Henri Decaisne

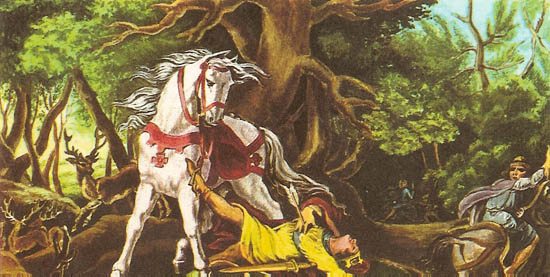

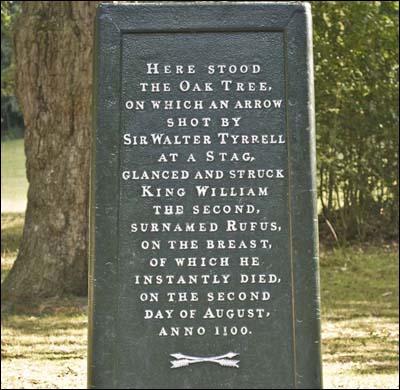

Many Crusaders had to act in this fashion in order to finance their Crusading activities. William even considered a similar bargain with the Duke of Aquitaine. On the 2nd of August 1100, William went hunting in the New Forest, probably near Brockenhurst, together with his younger brother Henry. Unexpectedly, the monarch was fatally wounded by an arrow that pierced him in the chest. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, William was “shot by an arrow by one of his own men.” The king’s killer was a nobleman Walter Tirel, who accompanied William among his men and while trying to shoot a stag instead killed his liege lord accidentally. A frightened murderer escaped. There are different descriptions of William’s death, and its later versions were modified and embellished.

William of Malmesbury, born in 1095, was a Benedictine monk from the Malmesbury Abbey. Interested in history and always searching for primary sources, he wrote the books ‘Deeds of the Kings of England’ (449 to 1127) and ‘Recent History’ (1128 to 1142). Although the murder of William Rufus happened when Malmsey was only 5, he described what happened during the hunt:

“The sun was now declining, when the king, drawing his bow and letting fly an arrow, slightly wounded a stag which passed before him… The stag was still running… The king, followed it a long time with his eyes, holding up his hand to keep off the power of the sun’s rays. At this instant Walter decided to kill another stag. Oh, gracious God! The arrow pierced the king’s breast. On receiving the wound the king uttered not a word; but breaking off the shaft of the arrow where it projected from his body… This accelerated his death. Walter immediately ran up, but as he found him senseless, he leapt upon his horse, and escaped with the utmost speed. Indeed there were none to pursue him: some helped his flight; others felt sorry for him.”

The dead monarch’s corpse was delivered to Winchester Cathedral and buried without ceremony there. William was not married and had no children because he was allegedly homosexual, which made him quite unpopular back then. Some historians think Walter Tirel could have acted upon the orders of William’s younger brother, and the tremendous speed with which Henry seized William’s treasures at Winchester and his throne indirectly prove that there could be some conspiracy against William. With the support of Gilbert and Roger de Clare, Henry declared himself King of England and was crowned only 3 days later on the 5th of August by Maurice, Bishop of London. Robert was away and could not seize the opportunity to become king.

For years, William Rufus’ reputation suffered because of his lack of piety and his lack of wife. However, we have to give a more or less fair estimate of William as a king: he was an intelligent and capable ruler, and his disputes with Anselm happened because he was claiming the same rights his father, the Conqueror, had exercised. History is always written by the winning party, and back then it was often written by churchmen, so everything about monarchs who were unorthodox in an age when their habits and inclinations were not considered normal should be taken with a pinch of salt.

After Robert Curthose’s return from the Holy Land, he threatened to invade England and fight for the throne. However, Henry agreed with his elder sibling that Robert acknowledged him as the sovereign of England in return for an annual payment of £2,000, and Robert accepted that. Tirel fled to France and never returned, but his son kept his estates in England, which again indirectly proves that Henry I could have been behind the plot against William II. The Clare family benefited from the death of William Rufus. Of course, the committed fratricide cannot be proved, but such suspicions exist.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville