My dear friends and readers!

I’m pleased to inform you that I’m currently having a book tour, in which I’m visiting various blogs and discussing Anne Boleyn for my new book Between Two Kings. Today, my new article was published on Queenanneboleyn.com (you can find it here).

Anne Boleyn and King François I of France: a woman who was probably more French than English, and one of the most powerful men in Christendom during the Renaissance era. These intriguing and fascinating historical figures are the two main characters of my new novel Between Two Kings. Much of Anne’s life is connected with France, a country of culture and arts, with such instantly recognisable national icons as Château de Fontainebleau and Palais du Louvre.

When did Anne and François I meet for the first time? Did the King of France support or condemn Anne for taking Henry from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon? What was François’ reaction to Anne’s execution?

Anne spent many years in France, where she learnt courtly manners and received a stellar education, the best available for a noblewoman of non-royal birth in the Renaissance era. For a short time, she served Mary Tudor, who returned to England when she became a widow. However, Anne didn’t go back home and instead joined the household of fifteen-year-old Claude, probably because the new Queen of France took a liking to the young girl and maybe due to her fluency in both English and French. Anne stayed at the French court until she was called back to England in late 1521, and she had many chances to observe and probably interact with the young and flamboyant François.

I want to say a few words about François. He was the only son of Charles d’Orléans, Count d’Angoulême, and Louise de Savoie; he was a great-great-grandson of Charles V of France.

When François was born on 12th September 1494, he wasn’t an heir apparent to the throne, and he wasn’t first in the line of succession, because Charles VIII of France was still young and was expected to have sons with his wife, Anne of Brittany. A tragedy took the Valois family by surprise, coming like a thunderbolt from a clear sky: the young king struck his head on the lintel of a door and died shortly thereafter, which resulted in the accession of Louis XII of France, who didn’t have any surviving male issue. Due to the Salic law, Louis XII’s daughters, Claude and Renée, couldn’t rule, and François became an heir presumptive at the age of four.

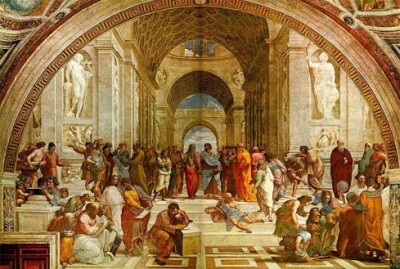

François I was an intelligent and impeccably educated man, influenced by the new progressive ideas of his time which originated in Italy. He is rightfully considered the first Renaissance King of France. During his reign, François oversaw France’s profound advancement from medieval culture to enlightenment by patronizing many great artists of his time, including Andrea del Sarto and Leonardo da Vinci, and promoting the spreading of new thinking in art, architecture, politics, science, and literature.

A tall and handsome man, the king had a weakness: he loved women, and they all adored and loved him back, even those whom he left behind. He is often labelled as one of the most notorious womanizers among the Valois kings, although many of his rumoured sexual exploits are embellished and exaggerated. For example, there was a tale that he had a mistress at the age of ten, and I cannot believe that it is true; another tale is that he built Château de Chambord to stay close to one of his numerous mistresses.

Anne may have seen François on 9th October 1514, the day of Mary Tudor’s marriage to Louis XII at Abbeville. François surely attended the wedding ceremony and lavish festivities, but there is no contemporary information about Anne’s presence there. We do know that Thomas Boleyn wrote a letter to Archduchess Margaret, asking her to release his youngest daughter from her duties so that she could accompany Mary Tudor on her journey to France. Anne could have joined the princess’s party on the way to Paris, or she could have arrived there later.

Anne may have personally witnessed many events unfolding in France at the beginning of François I’s long reign. As her real age and the early years of her life are all wrapped in a fog of enchanting mystery, we can only imagine and visualize what Anne might have done and seen in France.

If we take 1501 as the year of her birth, she could have accompanied Queen Claude and François’ mother, Louise de Savoy, on their journey to Marseilles in October 1515 to welcome the king back after his triumph at Marignano. Regardless of her age, as one of the queen’s maids-of-honour, Anne would have participated in Claude’s coronation at the Basilica of St Denis on 10th May 1517 and in her grand entry into Paris.

Anne must have attended the Field of Cloth of Gold, the infamous meeting of King Henry VIII and King François I in June 1520, just outside Calais. According to Eric Ives, Queen Claude and her ladies were an impressive sight and took the two kings and the audience by storm when they appeared at the joust; that encounter might have been Anne’s first meeting with her future husband – Henry VIII.

On these and some other occasions, Anne definitely saw François, who might have taken notice of Anne, although he might have considered her too young to become his mistress. She surely met him in private as well, when he came to Claude’s quarters and Anne served them.

Her enemies claimed that Anne became a woman of loose morals in France. Yet, Claude’s life was a continuous succession of frequent pregnancies, and she spent much time in confinement, preferring to live in the Loire Valley, in Château d’Amboise and Château de Blois. As her lady, Anne would have been with the queen, where she couldn’t have been influenced by the French frivolities. Moreover, the existing descriptions of Claude of France show her strong devotion to God, her strict moral code, and her appreciation of modesty and humility in her ladies.

That dispels the myth of Anne’s immoral life at the French court and indirectly confirms that, most likely, she was a virgin when she returned to England. If Anne had behaved promiscuously and become a fallen woman, Claude would have dismissed her from the royal household. Instead, the French queen liked Anne and was frustrated when her young maid was ordered to return to England. The years spent in Claude’s household had an enormous influence on Anne, and later, when she became Queen of England, her court would bear a likeness to Claude’s in her insistent encouragement of her ladies-in-waiting to be pious and to read the Bible regularly.

After Anne’s return to England and her involvement with Henry, Anne didn’t see François again until she visited Calais with Henry in October 1532.

Henry had been fighting to rid himself of Catherine for more than six years, and this conflict had effectively split his kingdom into those who defended Catherine and those who supported the Boleyn-Howard faction. Henry was prepared to go to any lengths to secure the legitimacy of his marriage to Anne, including obtaining the King of France’s support. Another purpose of the meeting was to introduce Anne in Calais as England’s future queen consort, effectively flaunting his relationship with a woman who was queen in every way but name.

Not surprisingly, Henry encountered a few hindrances to the successful completion of his plan. His romance with Anne was an outrageous scandal throughout Christendom, and Catholics branded her as a whore and a vile, heartless usurper, who pushed a saintly and pious rightful queen off of her throne. François was in a tricky situation: receiving Anne and Henry with honour and friendship could have earned him the disapproval of other Catholic kingdoms and even the pope. At the same time, France needed England as an ally against Spain. Eleanor of Austria, François’ second wife and Emperor Charles V’s sister, categorically refused to greet the indecent Boleyn woman, and even Marguerite d’Angoulême (François’ elder sister) remonstrated against meeting Anne.

Ultimately, the political aspect outweighed all of François’ doubts, and the meeting proceeded as planned, but without his wife and his sister. After Marguerite’s demurral, François suggested that the Duchess of Vendome would greet Anne in Calais, which might have injured Anne’s pride because the Duchess was known for her notoriety in France.

Anne spent ten days with Henry, living like a queen, sparing no expense on opulent celebrations, and being escorted everywhere by her royal “fiancé”. Then she remained in Calais where she was entertained by the people while Henry travelled to the French court in Boulogne to spend four days with his rival, François. The two kings had what Ives described as a “stag party” – ‘the great cheer that was there, no man can express it.’

After Henry’s return, on 27th October 1532, Anne made her triumphal entry in the middle of the grand banquet in François’s honour, walking proudly and with the purpose to impress and tempt a little bit; she was followed by a masque of ladies. Well-curved women in magnificent, eccentric attire, the glitter of gold, satin, and brocade, and the splendour of the banqueting chamber shining in torchlight: what a grand spectacle it must have been!

The Tudor Chronicler Edward Hall describes Anne’s entrance to the banquet:

“After supper came in the Marchiones of Penbroke, with. vii. ladies in Maskyng apparel, of straunge fashion, made of clothe of gold, compassed with Crimosyn Tinsell Satin, owned with Clothe of Siluer, liyng lose[loose] and knit with laces of Gold: these ladies were brought into the chamber, with foure damoselles appareled in Crimosin satlyn[satin], with Tabardes of fine Cipres[cypress lawn]: the lady Marques tooke the Frenche Kyng, and the Countes of Darby, toke the Kyng of Nauerr, and euery Lady toke a lorde, and in daunsyng[dancing] the kyng of Englande, toke awaie the ladies visers, so that there the ladies beauties were shewed.”

François was invited to dance by one of the masked women, not knowing that she was Anne Boleyn. Anne’s reputation as a dancer of divine talent would lead us to believe that François must have admired her dancing skills as she moved across the chamber with lightness and astonishing, catlike grace. Soon Henry fell into a deep, childlike excitement and commanded that everyone remove their masks in order to contemplate the beauty of the women. François might have been surprised at the realization that his partner had been Henry’s mistress, Anne Boleyn.

We can speculate that Anne and François might have had a private talk, where he could express his support for her matrimonial plans, regardless of whether he actually favoured her upcoming nuptials with Henry. Kings often play games with foreign monarchs and their consorts, and they also often change their plans and alter their political strategies to make them fit their country’s interests.

In reality, François, a Catholic king, couldn’t proclaim his support for Anne and Henry’s marriage, but he could still make promises, even if he didn’t follow through with them. After news of the scandalous wedding ceremony spread throughout Europe, he never acknowledged Anne as Queen of England, and she must have felt betrayed. In addition, François didn’t permit a betrothal of Anne’s daughter, Elizabeth, to Charles de Valois, Duke d’Orléans, François’ third son with Claude of France, to proceed.

Anne had another important link to François I. William Camden, a chronicler writing during Elizabeth I’s reign, wrote that Anne had served not only Queen Claude but also Marguerite d’Angoulême, an outstanding intellectual figure of the French Renaissance. Many historians make a connection between Anne’s interest in the Reformation and Marguerite’s support of religious reform to prove that Anne spent at least some time in Marguerite’s household. However, Eric Ives notes that this is highly unlikely, saying:

“When reporting Francis I’s complaint in January 1522 about Anne leaving France, the imperial ambassadors described her quite unequivocally as one of his wife’s ladies, just as she had been in 1515.”

I tend to believe that Anne was close to Marguerite but didn’t serve in her household. We have two letters from Anne to Marguerite, and in one of these letters, she wrote that “The Queen [Anne Boleyn] said that her greatest wish, next to having a son, is to see you again”. Ives stated that there were certain parallels between “Anne expressing her faith in fine illuminated manuscripts and Marguerite doing the same”. There was some kind of relationship between the two women, who shared interests in new religious ideas; perhaps Anne gained her evangelism in France.

The meeting in Calais was the last encounter between Anne Boleyn and François I. When Anne was apprehended, François didn’t make any public pronouncements: neither a shocked protest of her arrest nor any kind of disparagement of Anne for her alleged crimes was voiced by him. The King of France was more interested in preserving his alliance with England than the fate any particular person.

Although he had known Anne personally since her early youth, I don’t believe that he experienced either heartbreak over her death or outrage at the ruthless treatment of her by Henry. However, François wasn’t a cold-blooded tyrant like Henry, so I want to hope that he regretted Anne’s death in the depths of his heart, which is how I portrayed him in my novel, Between Two Kings.

Anne and François had much in common: they were eccentric and extravagant, as well as generous and protective of their friends while being pitiless and cruel to their enemies; they both were impeccably educated, and they “radiated” Renaissance; and in these respects, they could be seen as well-matched equals.

In Between Two Kings, Anne marries François I, and they join forces to devise a plan of revenge against Henry and those who had grievously wronged Anne in England. Maybe they will find happiness, and Anne will fall in love with François, but you will have to read the book to know the outcome.