A Boy King

Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547, leaving his son, Edward Tudor, to inherit the English throne.

At first, Henry’s death was a secret even to his only surviving legitimate son, Edward Tudor. His uncle – Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford – and Sir Anthony Browne escorted Edward to Enfield Manor in Middlesex. Then Hertford announced the tragic news to his nephew.

Now Hertford had to put the boy king on the throne and to secure his own dominance in the government. Hertford’s plan was to take Edward to London and to arrive at the Tower of London on the 31st of January, 1547.

As the young Edward VI and his closest entourage were setting off from Enfield, the proclamation of his accession to the English throne was being read in Westminster Hall.

Few inhabitants of England remembered the last time a monarch was proclaimed to his people. It had last happened in 1509, when the young Henry VIII, two months away from his eighteenth birthday, had been the great hope for a glorious and prosperous future for England after Henry VII’s death.

A few days after the late king’s death, the council of sixteen executors (Council of Regency), appointed by Henry VIII, met together at the Tower of London. The late king had made a final revision to his last will and testament on the 30th of December, 1546. This document confirmed the line of succession: Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth, and, following them, the Grey and Suffolk families. The councilors proclaimed their loyalty to Henry’s last will and testament.

The Council of Regency chose to give the Earl of Hertford almost regal power, making him ‘the Protector of the king’s realms and dominions and Governor of his most royal person’. The ambitious Hertford must have done a deal with some of the executors, including with William Paget, private secretary to Henry VIII, and with Sir Anthony Browne, Master of the Horse.

The following day, all of these councilors met again in the Tower to hear Henry’s will read out from beginning to end. Then they all visited Edward V and took their oaths of fealty to their new sovereign. They also secured Edward’s consent to their election of Hertford as Lord Protector and Governor.

Edward was surrounded by his father’s executors and the members of the English nobility, who all treated him as their new king. He must have been overwhelmed with awe, as he watched the theater of monarchy where he himself was the chief actor.

The Council of Regency planned down to the last word and gesture the form of Edward’s coronation in Westminster Abbey. In spite of being very young, Edward must have understood that his father’s death changed his life, and he became a king who had many subjects. Yet, the boy king wasn’t able to comprehend the tough world of Tudor court politics and the intricacies of state affairs. Edward was a boy king, who flourished in a lively court life, but who could not rule for himself.

On the 14th of February, 1546, Elizabeth Tudor, Edward’s sister, made clear her loyalty:

“May God long keep your majesty safe and further advance (as He has begun to do) your growing virtues to the utmost. From Enfield the 14th of February.

Your Majesty’s most humble servant and sister, Elizabeth.”

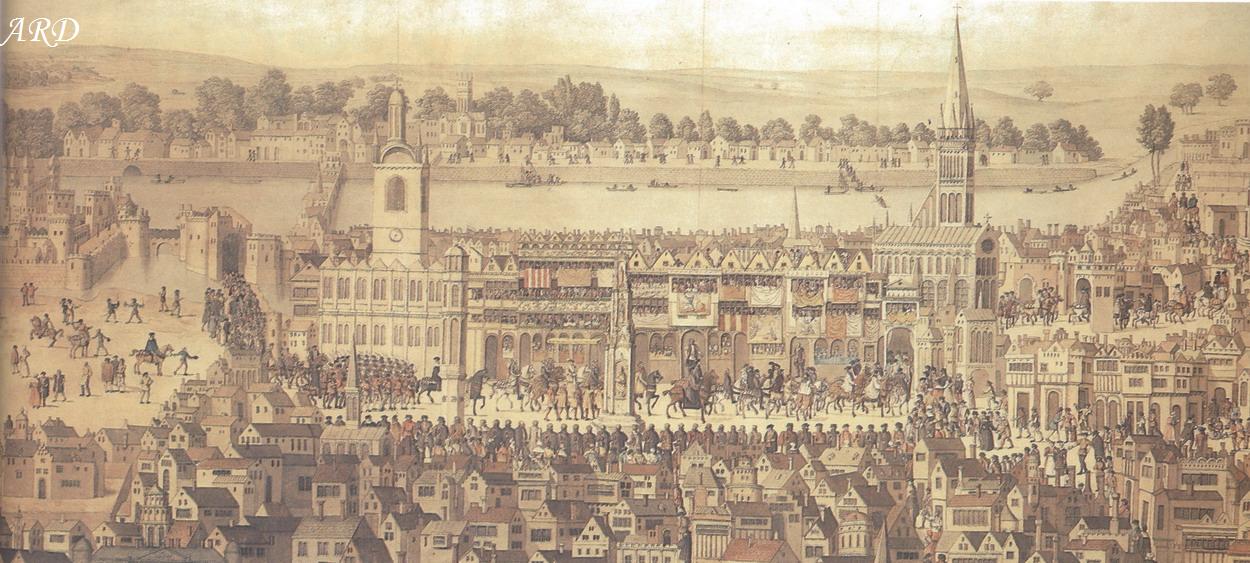

On the 20th of February, 1547, the lavish coronation ceremony of Edward VI took place in Westminster Abbey. Actually, the pre-ceremonies actually began the day before the official event. In the afternoon of the 19th of February, the boy king left the Tower of London and processed through the streets of London. The boy king was richly attired in dazzling white velvet, embroidered in silver thread and decorated with lovers’ knots made from pearls, diamonds, and rubies. The royal messengers, gentlemen, trumpeters, chaplains, and esquires were all walking; they were followed by the nobles and foreign ambassadors on horseback.

Coronation of King Edward VI

On the way to Westminster Abbey, King Edward VI walked under a canopy, carried by the barons of the Cinque Ports. The king’s uncle, Edward Seymour, who was the Lord Protector of the English realm, stalked ahead of his nephew, carrying the crown. The Duke of Suffolk carried “the ball of golde, with the crosse”, while the Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset, carried the scepter. Edward was flanked by the Earl of Shrewsbury and the Bishop of Durham, followed by John Dudley, Thomas Seymour, and William Parr, Marquess of Northampton, who all bore the boy king’s train.

Chronicler Charles Wriothesley wrote of this event:

“The twentith daie of Februarie, being the Soundaie Quinquagesima, the Kinges Majestie Edward the Sixth, of the age of nyne yeares and three monthes, was crowned King of this realme of Englande, France, and Irelande, within the church of Westminster, with great honor and solemnitie, and a great feast keept that daie in Westminster Hall which was rychlie hanged, his Majestie sitting all dynner with his crowne on his head; and, after the second course served, Sir Edward Dymmocke, knight, came ridinge into the hall in clene white complete harneis, rychlie gilded, and his horse rychlie trapped, and cast his gauntlett to wage battell against all men that wold not take him for right King of this realme, and then the King dranke to him and gave him a cupp of golde; and after dynner the King made many knightes, and then he changed his apparell, and so rode from thence to Westminster Place.”

Due to Edward’s youth, the traditional coronation ceremony, used since 1375 and described in the Liber Regalis, had been altered. It had been shortened because of his young age: it took only seven hours instead

of the standard twelve hours.’ The length of the coronation banquet had been cut as well.

One of the most notable changes was that the role of churchmen, who were traditionally the intermediaries between God and the monarch, was significantly reduced. According to Chris Skidmore’s book “Edward VI: The Lost King of England”, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, had also modified the coronation oath so that “Reformation of the Church could now be enabled by royal prerogative, the king as a lawmaker”.

Sitting on his throne, Edward VI was then anointed and crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury with three crowns: the St Edward’s crown, the imperial crown, and a custom-made lighter crown.

Trumpets blew between each crowning, and the choir then sang a Te Deum, which was the traditional accompaniment to this part of the ceremony. A ring of gold was set on Edward’s finger; then Edward Seymour, the Lord Protector, and other nobles approached their king and kissed his left cheek.

From the very beginning of Edward VI’s reign, the government was ruled by Edward Seymour, the king’s uncle. Driven by ambition and greed, Hertford created for himself a portfolio of lofty titles and offices by March 1547: he was Duke of Somerset, Earl of Hertford, Viscount Beauchamp, Lord Seymour, Governor of the king, Protector of his people, realms and dominions, Lieutenant General of his Majesty’s land and sea armies, Treasurer, Marshal of England, and Knight of the Garter. Although at first, he had to act upon the advice and consent of Henry VIII’s executors, soon Edward Seymour began to govern like an absolute monarch.

The story of Edward Seymour and his brother, Thomas Seymour, will be covered in other articles.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2018 Olivia Longueville