Anne Boleyn emerged from the Tower of London at 5pm on Saturday the 31st of May 1533. She had spent the previous several days in the queen’s chambers in the Tower. According to contemporary sources, the last day of spring was sunny, bright, and warm, and the sky was an unbroken azure, spreading out above Anne in a serene canopy. It must have seemed to her that nature itself foreshadowed her success as the soon to be Queen of England and Henry VIII’s wife.

Tower. According to contemporary sources, the last day of spring was sunny, bright, and warm, and the sky was an unbroken azure, spreading out above Anne in a serene canopy. It must have seemed to her that nature itself foreshadowed her success as the soon to be Queen of England and Henry VIII’s wife.

Anne was dressed in the French fashion. The coronation procession from the Tower was en-route for Westminster. It was headed by twelve servants of the new French ambassador to England – Jean de Dinteville, who was King François I’s maître d’hôtel. This illustrates Anne’s pro-French preferences, which her numerous foes considered unpatriotic, calling her a Frenchwoman. This, nevertheless, was true in many aspects because Anne loved France, French culture and fashions.

Then appeared the gentlemen of the royal household, who were by tradition the eyes and ears of the reigning monarch whom they served. Next came the nine judges clad in their scarlet gowns and hoods, followed by the Knights of the Bath. Then moved the state council, the ecclesiastical magnates, and the peers of the realm. At last, behind them emerged the queen’s fabulous litter.

Eric Ives describes Anne’s appearance and her attire:

“She {Anne} was dressed in filmy white, with a coronet of gold. The litter was of white satin, with ‘white cloth of gold’ inside and out, and its two palfreys were clothed to the ground in white damask. In ravishing contrast was the queen’s dark hair, flowing loose, down to her waist. Over her was a canopy of cloth of gold held up by the barons of the Cinque Ports. Then came her own palfrey, also trapped in white. Twelve ladies in crimson velvet rode behind.”

Several more riders and carriages, as well as thirty gentlewomen on horseback, each of them richly attired, were followed by the king’s guard in two files, one on both sides of the street. All of the servants in the livery of their masters or mistresses were at the end of the long procession. Most definitely, many of them did not support Anne and viewed her as the usurper of Catherine’s place in the king’s affections, but they participated in the coronation out of duty and fear, for they would find themselves on the receiving end of the king’s wrath. And Anne was truly magnificent!

Observers reported that some notable people were missing in the cortege. Neither the king’s sister, Princess Mary Tudor, nor her daughter, Frances, was present, nor Lady Elizabeth Stafford, Duchess of Norfolk. Anne’s step-grandmother – Agnes Howard née Tilney, Dowager Duchess of Norfolk – rode in one of the carriages, along with either Anne’s mother, Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire, or Margaret Wotton, Dowager Marchioness of Dorset. However, the absences of the king’s sister and her daughter, Frances, can be easily discounted: Princess Mary Tudor had suffered from consumption for months and was very ill at the time of the coronation, while her daughter was barely out of childhood. The Duchess of Norfolk could have chosen to stay away from her ruthless husband, from whom she had separated in 1534 after their notorious quarrel. Thomas More, another doubter, was also missing, as he deliberately refused to attend.

For the inhabitants of London, this was their first glimpse of the scandalous, extraordinary woman who had changed the life of the country. For Anne, the coronation procession was her first chance to see the reaction of the English people to her new station. Hostile accounts disparaged everything: according to a report that reached the Imperial court in Brussels, the crowds did not cheer and take their hats and toques off when Anne passed. Some say that later, Anne complained to Henry about the cold reception with gloomy throngs on the streets. At the same time, Eric Ives thinks that spectators were ‘more curious than either welcoming or hostile’, so perhaps the most negative things from the coronation reports should be given little credit to.

Disappointed by their reaction, Anne must have felt a blend of dejection, anxiety, pride, and triumph. Regardless of their opinion of her, her beloved Hal chose her to be his queen, and soon she would give the country a long-awaited male heir. Anne was heavily pregnant at the time of the coronation, and I can imagine her placing a hand on her swollen stomach, hidden by her gown, as she thought of a Tudor prince she presumably carried. Defiance was one of her most controversial qualities, and she had committed her first act of defiance of social norms years ago, when she had accepted the monarch’s marriage proposal while Henry was still married to Catherine of Aragon. As she contemplated the sullen people who did not want her to be their queen, she probably decided that if defiance was her destiny, she would be defiant again against all the rules if necessary.

What shall this day bring to me, June?

A brilliance with every summer hue:

The cloud-white dream of happiness,

Shot with the primrose sunshine through…

Or shall my coronation bring me pain,

People do not want me, their stillness say it,

The day will see me crowned despite them,

Yet, making ancient rhyme of lovers sore,

As if my joy is dead, my sadness lingers yet.

Oh, Henry! They love you, their dear prince,

Will you work to make them favor me too?

Some say your love is like a flight of doves –

With wanton wings, with promises and ways,

But flashing white against the sky only to die.

You may love, and sigh, and soon forget?!

I do not believe! You are my Hal forever!

A thousand roses will blossom red for us,

And a thousand hearts will be gay, I pray,

For the summer of love lingers just ahead,

And our boy is on his way to a Golden age,

Fate will have him born in autumn for us.

The moon and the stars will weave new spells

Of love – for my Hal, for me, and for our boy,

The music of marriage bells will sound to us.

Oh, sadness – stay behind and die in May!

I’ve started writing a lot of poetry as of late, and I cannot explain why I need it. Now I can write both prose and poetry, and it is not difficult for me at all. In this poem, which I composed to describe Anne’s feelings during her coronation procession, I strove to stress her strong faith in Henry’s love and in her happiness with him, and to remind of their expectation that the child in her belly was a boy. The reference to England’s Golden Age foreshadows Elizabeth I’s glorious reign, but at that time, Anne and Henry could not know about it. I hope you like this poem.

Soon the coronation party made its grand entrée into the City of London. During the reign of Henry VIII, this historical place was mostly confined to that small area with a population of about 100,000 people. The City was the center of business and finance, where trade guilds and livery companies elected the Lord Mayor every year. Since the days of William the Conqueror, the City has retained its independence from royal interference. Thus, Anne’s coronation procession was a significant event aimed at showing the king’s second spouse to the population of London.

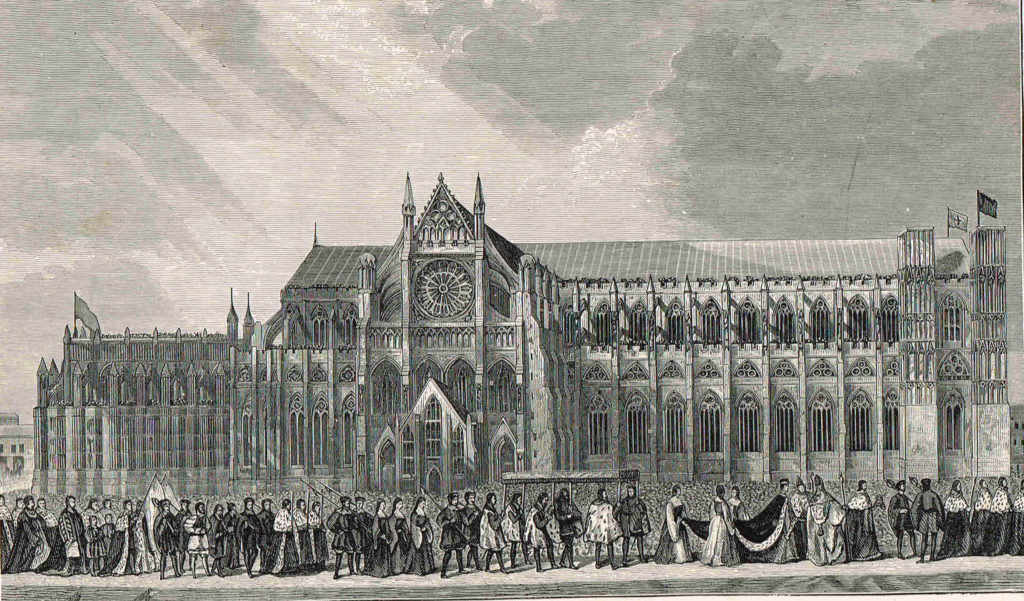

There were 6 traditional points for pageants through the city and additional 3 locations, each of them opulently decorated for Anne as a sign of King Henry’s undying devotion to her. On the 1st June of 1533 after what must have seemed an eternity of waiting, the coronation procession entered Westminster. The witnesses began assembling in Westminster Hall from 7am, but it was just minutes before 9pm that Henry’s wife appeared there.

Anne must have breathed out a sigh of relief as they approached Westminster Abbey, where she would finally be crowned; she was in a family way, so she must have been tired, in spite of her exhilaration. Climbing down from her litter, she and her ladies set out along a route carpeted with cloth of blue ray all along the several hundred yards between the dais of the hall and the high altar of the abbey. Anne was watched by all the peers of the realm and foreign ambassadors, aldermen and judges in scarlet, the monks of Westminster and the staff of the Chapel Royal, all in their sumptuous copes, as well as four bishops, two archbishops and twelve mitred abbots in full pontificals. The abbot of Westminster had his complete regalia.

Ives describes Anne’s appearance in Westminster in these moments:

“Anne was resplendent in coronation robes of purple velvet, furred with ermine, with the gold coronet on her head which she had worn the day before, though it is not clear that she followed tradition by walking barefoot. Over her was carried the gold canopy of the Cinque Ports, and she was preceded by the sceptre of gold and the rod of ivory topped with the dove, and by the lord great chamberlain, the earl of Oxford, bearing the crown of St Edward…”

On the way to the high alter, Anne was supported, according to custom, by the bishops of London and Winchester. The Dowager Duchess of Norfolk carried her long train, and a myriad of her ladies and gentlewomen, each of them accoutered in scarlet with appropriate distinctions of rank. Perhaps having an enigmatic expression on her face, Anne seated herself into St Edward’s Chair, draped in cloth of gold.  The grand chair was situated on a tapestry-draped dais two steps high, which was itself set on a raised platform carpeted in red. For a few moments, Anne sat there before she stood up, and the official ceremony of her coronation started.

The grand chair was situated on a tapestry-draped dais two steps high, which was itself set on a raised platform carpeted in red. For a few moments, Anne sat there before she stood up, and the official ceremony of her coronation started.

A solemn mass was performed by the bishop of Westminster. Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, who supported and adored Anne, prayed over her as the royal wife prostrated herself before the altar, despite her pregnancy. She was anointed by Cranmer before she walked back to St Edward’s Chair, where the archbishop crowned her and handed to her the sceptre and the rod of ivory. It is remarkable that Anne was the first female monarch who was crowned with the crown of St Edward, which was previously used to crown only a reigning ruler. This was King Henry’s obvious attempt to make others see the significance of his marriage to Anne.

A bit later, the heavy crown of St Edward was replaced with a lighter one, of course for the queen’s convenience. The service continued: Anne took the sacrament and made the offering at the shrine of the saint. As his beloved cemented her place in history as the new Queen of England, King Henry watched the ceremony from the special stand from behind a latticework, which had been erected in the abbey so that the sovereign could see everything incognito.

This mystique of monarchy belonged to Queen Anne Boleyn. At that time, she could not predict that in about three years, she would die on her husband’s orders for crimes she did not commit. Her emotions must have alternated between celestial delight, unutterable joy, and a feeling of unprecedented triumph. It seemed to Anne that a golden future stretched before her, a future composed of nothing but hope, new victories, and contentment.

The sun has shone upon all of me and fed

My heart and soul’s rhythms with light,

Raised me from dust to a rose, big and red,

Now I’m Henry’s queen, my life is bright!

A white star-flower of joy I will encounter

As sweet darkness envelops the earth

This night – no, not my wedding night,

But the first night of me being a queen.

In the dark, my Hal is still my sun of life,

He will guard my body and sleep tonight,

Holding all the starts in the sky true to us,

Reassuring me that we will defeat any foe.

In the morning, as I will open my eyes again,

From heaven, Hal’s sun will stoop to breathe

A flower of our love into the air in our room.

Surely, my life is now not beneath my Hal’s,

For I became his true queen in Westminster,

Beloved forever and feeling his kindness,

His care for our son growing inside me.

All make me believe it will last forever.

So, from the ashes of my odd sadness,

That lingers in my bosom like a dirge,

Will beauty and hopes grow in my life.

I’ve also written the poem describing Anne’s feelings after her coronation. I may be wrong, but I do not think she had any fears about her future at that time. I believe that Anne loved Henry, perhaps not from the very beginning of their romance, but she fell in love with him somewhere along the way. The long way to their wedding and Anne’s coronation. Nonetheless, the mentioned “odd sadness” foreshadows that Anne’s happiness with Henry would not last long. The “odd sadness” lingers “like a dirge”, which foreshadows her tragic death after an awful lot of unhappiness Anne would experience in her marriage to the king after his passion for her cooled off.

And so far, the nobility of England saw Anne being crowned and accepted or were forced to accept her as queen in the sight of God. Whatever Anne’s fate would be, the mystique of a queen was unbreakable even after her death.

William Shakespeare would declare a generation later:

“Not all the water in the rough rude sea

Can wash the balm from an anointed king.”

“Two poems were written by Olivia Longueville

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2019 Olivia Longueville

Beautiful poems you describe with beauty and pass Anne’s feelings on her triumph as an anointed queen with great perfection

Thank you so much!