On the 12th of October 1537, Queen Jane Seymour gave birth to the future King Edward VI at Hampton Court Palace. The ordeal was a horrendous one, for the birth had taken two days and three nights. Nevertheless, she must have been in an elated frame of mind because she fulfilled her husband’s most cherished dream. Jane triumphed over her predecessors – Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn. She could not know that her victory would be short-lived.

Portrait by Hans Holbein, Kunsthistorisches Museum

In the days which followed Edward’s birth, lavish celebrations and festivities took place at Hampton Court Palace. Henry VIII, who was obsessed with male heirs and had disposed of two wives in his quest for a healthy son, was overwhelmed with happiness and pride. A two-thousand gun salute was fired from the Tower of London, and a fierce sense of joy swept through the entire country. At last, for the first time in many years, England had her Prince of Wales.

The experience of even royal childbirth in Tudor period was risky at best. Nonetheless, at first Jane felt better and was expected to fully recover. Henry lavished his consort and her family with affections and rewards, and without a shadow of a doubt, he interpreted his son’s birth as a God’s sign that his marriage to Jane was blessed by the Almighty. He must have been absolutely confident that Jane was his only “true” wife, unlike Catherine and Anne. The king proclaimed Edward Prince of Wales, and he also elevated Edward Seymour to Earl of Hertford.

Trouble stalked Jane like an invisible lethal enemy: soon she contracted childbed fever, or puerperal fever. In spite of the royal physician’s efforts to at least stabilize her condition, the ailing queen had no strength to fight the sickness, and her health was worsening day by day. Everyone at Hampton Court prayed for the queen, and on the 17th of October, her condition improved a little. However, by the 24th of October, her fever intensified, but she was still alive. Physicians said that if she had survived the night, she could win her fight with death.

Sir John Russell wrote to Thomas Cromwell on that day:

“The king was determined, as this day, to have removed to Esher, and, because the queen was very sick this night, and this day, he tarried; but tomorrow, God willing, he intendeth to be there. If she amends he will go and if she amend not, he told me, this day, he could not find it in his heart to tarry; for, I assure you, she hath been in great danger yesternight and this day; thanked be God, she is somewhat amended, and if she ’scape this night, the fyshisiouns [physicians] be in good hope that she be past danger.”

Queen Jane Seymour and Prince Edward n the ShowTime Series The Tudors

Once puerperal fever was the dreaded infection that killed many women. Centuries earlier, medics lacked scientific knowledge: there was no understanding of microbial infection, and no effective treatment for it. It was described in primitive terms as a “desecration”, perceived by doctors and females as an aspect of the natural world that felt too evil because women died within mere days after the first symptoms had appeared. They had no idea that the dirty cloths and hands during and after the labor would be a cause of infection. In fact, the remedies doctors used in the attempts to save women’s lives, often made it worse, only accelerating their deaths.

Their hopes were illusive, and Jane passed away on the 24th of October 1537. In a way, she was another victim of Henry’s obsession to have a son, just as Anne and Catherine had been. Most likely, the monarch viewed her death as her greatest sacrifice for him and for England. By dying before she could become an undereducated burden for her spouse, before he could get bored with her, Jane immortalized her name in Henry’s eyes for the sole reason of giving him little Edward. The disconsolate monarch was unable to stay at Hampton Court, so he hastily left for Westminster, where he shut himself away from the world and his sorrows.

Death of Jane Seymour (1847) by the French painter Eugène Devéria

Jane’s body remained in the chapel at Hampton Court for twelve days. Meanwhile, the final preparations for her burial were made. On the 12th of November, a grand ceremony was held in London in commemoration of the deceased queen. Jane’s stepdaughter, Lady Mary Tudor, acted as a chief mourner; she was truly grief-stricken, for she liked and respected Jane in life.

Wriothesley’s Chronicle sheds light on Jane’s funeral procession from Hampton to Windsor:

“There was a solemn herse made at Powles in London, and a solemne dirige done there by Powles queere, the Mayor of London beinge there present with the aldermen and sheriffs, and all the mayors officers and the sheriffe’s sergeants, mourninge all in blacke gownes, and all the craftes of the cittie of London in their liveries; also there was a knyll [knell] rongen in everie parishe churche in London, from 12 of the clocke at noone tyll six of the clocke at night, with all the bells ringing in everye parishe churche solemne peales, from 3 of the clocke tyll the knylls ceased; and also a solempne dirige songen in everye parishe churche in London, and in everie churche of freeres [friars], monkes, and chanons, about London.”

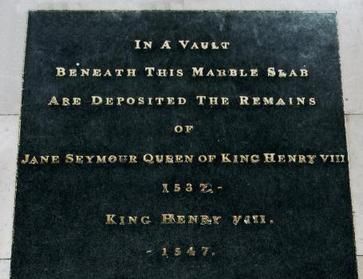

Queen Jane was interred in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle. During the next few years, Henry mourned for her, and, remarkably, it was the only mourning he had ever had for any of his six wives. He requested to be buried in the vault in the same chapel next to his “true and loving Wife, Queen Jane”. But in the era of a high infant mortality rate, having one prince was deemed not enough for the young Tudor dynasty, so Henry remarried Anne of Cleves in 1540.

I believe that Henry did not really love Jane Seymour. In his son-obsessed mind that was perhaps severely affected by the head injury he had received during the 1536 jousting accident, the title of ‘his favorite wife’ would automatically have gone to a wife who managed to provide him with what he most desired. Jane did not fail him, and that is why he worshiped her in death. If she had died giving birth to a daughter, or if she had produced a stillborn son, Henry would not have mourned for her, and would never have called her the love of his life. In this situation, he would have declared their union null and void, and would have forgotten about her quickly.

The following inscription was above Jane’s grave for a time:

Here lieth a Phoenix, by whose death

Another Phoenix life gave breath:

It is to be lamented much

The world at once ne’er knew two such.

Henry VIII did not suspect that Edward would die a childless teenager, just in several years after the king himself had breathed his last in 1547. His union with Anne Boleyn literally brought him the greatest fruit on the Tudor royal family tree. Fate has a bizarre sense of humor: the little Elizabeth, whose conception Henry considered the biggest flaw in his otherwise glorious life, would create her unparalleled legacy of forever being present in the annals of English and World History as England’s most extraordinary, powerful, intelligent, and illustrious Queen Regnant.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2019 Olivia Longueville