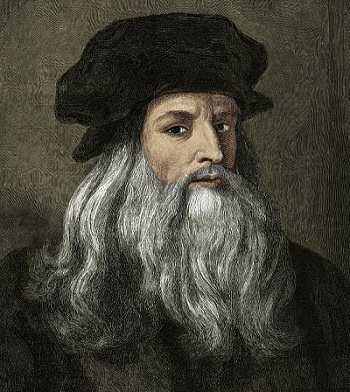

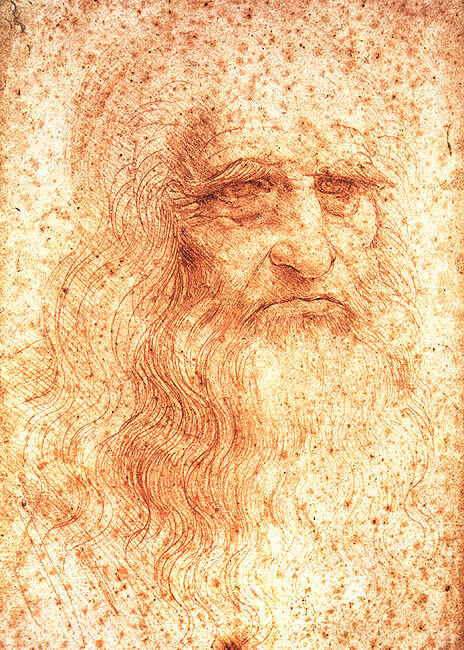

Leonardo Da Vinci was born on the 14 or 15th of April 1452 in the Tuscan town of Vinci, in the Republic of Florence. He was undoubtedly the quintessential Renaissance man, one who spent most of his life in Italy and his last years in France. Leonardo’s areas of interest were immensely diverse, ranging from the arts, including drawing, music, painting, literature, sculpture, and architecture, to sciences such as anatomy, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, geology, paleontology, cartography, botany, and even paleontology.

His career started as a garzone, or a studio boy, in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of the era, one patronized by Lorenzo de’ Medici known as Il Magnifico. It was where Leonardo met with Verrocchio’s apprentices who worked in the workshop: future famous painters such as Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and a few others. At the age of 20, Leonardo became a master in the Guild of Saint Luke (the Guild of artists and doctors of medicine).

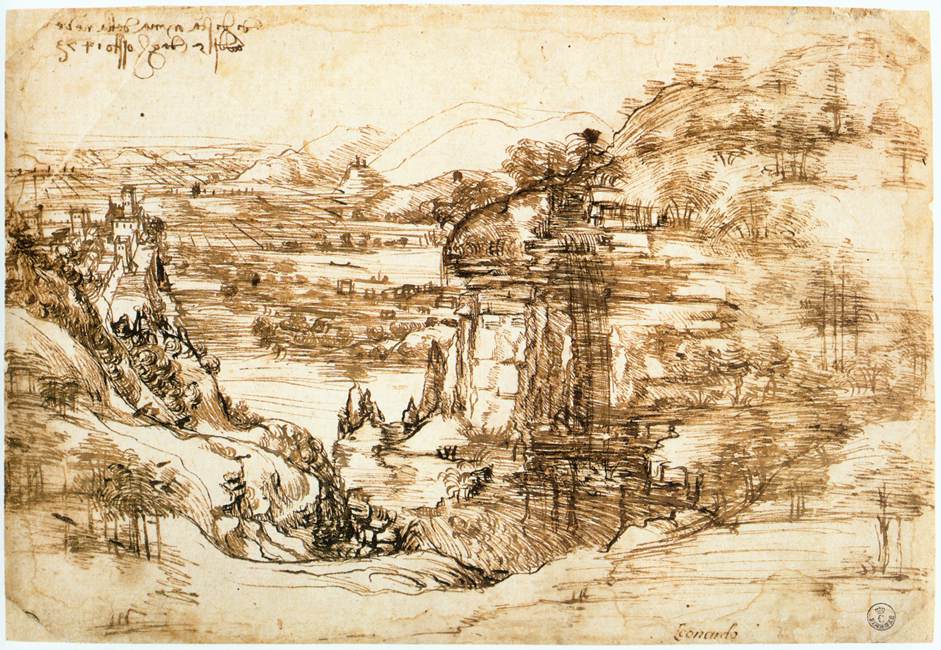

Leonardo’s earliest known work is the pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno Valley dated 1473. According to Giorgio Vasari, young Leonardo was the first to suggest making the Arno River a navigable channel between Florence and Pisa. Soon, in 1478, Leonardo received his first commission to create an altarpiece for the Chapel of St. Bernard in the Palazzo Vecchio (the town hall of Florence). According to other contemporary sources, Leonardo lived with the Medici family for some time and frequently worked in the garden of the Piazza San Marco, where Lorenzo’s Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets, and philosophers gathered on a regular basis.

Nevertheless, Leonardo’s restless heart hungry for knowledge didn’t let him spend his whole life in Florence. In 1482, the artist journeyed to Milan and worked with dedication for Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan also known as Ludovico Il Moro. During his Milanese sojourn, Leonardo created the illustrious painting ‘the Virgin of the Rocks’ for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, the famous ‘The Last Supper’ for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, and others. Leonardo also executed many other projects for Sforza, for example the creation of floats and pageants, and a huge equestrian monument to Ludovico’s predecessor Francesco Sforza.

After Sforza’s deposition in 1499, Leonardo escaped to Venice. For a short while, he served as a military architect and engineer for the Dodge of Venice, having devised peculiar methods to defend the city from naval attacks. Later the artist returned to Florence, which was free from the Medici rule at the time after the exile of the Medici family in 1494, for a short period. Interestingly, Cesare Borgia, the son of the controversial Pope Alexander VI, patronized Leonardo starting from 1502, having used his talent as a military architect, engineer, and cartographer.

Leonardo did not dedicate the rest of his life to Cesare’s service. In approximately a year, they parted their ways, and Leonardo returned to Florence. In October 1503, the artist commenced working on what would later become his most famous project – a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model for the Mona Lisa. He would work on the Mona Lisa until his twilight years. Leonardo also designed and painted a mural of ‘The Battle of Anghiari’ for the Florentine Signoria, which nowadays is often called ‘The Lost Leonardo’, for it is widely believed that this artwork was immured beneath the other frescoes created in later centuries in the Palazzo Vecchio.

In 1506, Leonardo was invited back to Milan by Charles d’Amboise, the French governor of the city and viceroy for Lombardy. Having returned there, Leonardo befriended Charles, but the Republican Government of Florence implored the governor to allow the Maestro to come and finish his earlier works. King Louis XII of France permitted him to leave, but afterwards Leonardo traveled between Florence and Milan for a few years. Leonardo’s famed pupils from the Milanese School of art include Bernardino Luini, Marco d’Oggiono, and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio.

When in the spring of 1513 Giovanni, the late Lorenzo de’ Medici’s second son, was elected the Pope, having assumed the name Leo X, Leonardo was summoned to Rome. From 1513 to 1516, Leonardo lived in the Apostolic Palace at the papal court, where he collaborated with the famed Michelangelo and Raphael. At his advancing age, Leonardo decorated a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver. Soon the artist became feeling rather unwell, perhaps having experienced multiple strokes. In Rome, the already sick Leonardo devoted much of his time to botany as he practiced it in the Vatican Gardens. Yet, for some reason Leonardo lost the Pope’s favor.

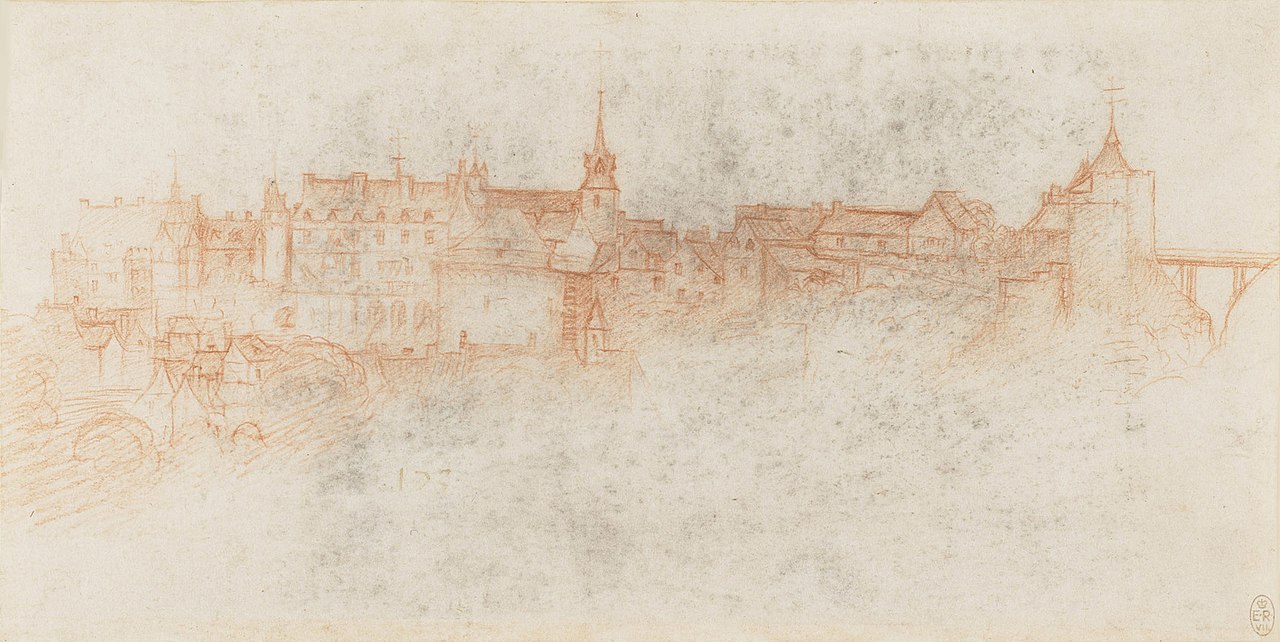

The next proposal from the art-loving King François came to Leonardo in time. He must have felt that his time in Rome was no longer productive, and there was little probability that the Pope would grant him a commission for some serious work. Perhaps it happened when Leonardo was present at the meeting of King François I and Pope Leo X in Bologna. Leonardo left Rome and, armed with his sketchbooks and drawings, journeyed to France, taking with him some of his pupils such as Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, known as Salai, and Francesco Melzi.

King François appointed the artist, whom he admired wholeheartedly, “Premier peinctre et ingenieur et architecte du Roy”, or “The King’s First Painter, Engineer, and Architect.” Most likely, Leonardo was flattered, exhilarated, and honored, for he had never before been elevated so highly in his artistic life, not even when he worked for Sforza in Milan. As young François loved his magnificent palaces in the Loire Valley, at the age of 64 Leonardo moved to Amboise to the grand Château du Clos Lucé, where his bedroom overlooked Château d’Amboise.

Having left Italy, Leonardo deprived his native people of the beauty of his three celebrated works – ‘the Mona Lisa’ (La Gioconda in Italian, La Joconde in French), ‘The Virgin and Child with St. Anne’, and ‘St. John the Baptist.’ Unfortunately, due to his health issues, Leonardo could no longer paint with his former masterful finesse, but he could work in other areas – in science, in particular in engineering and architecture. At the time, François desired to have a new residence constructed at Romorantin, so Leonardo drew up designs for the castle boasting the large gardens with fountains and a network of intricate canals. This palace was not built, but some elements of the artist’s design were present in other châteaux such as Chambord and Blois.

The ailing Leonardo developed a close and affable relationship with the King of France. The Château du Clos Lucé was connected by an underground passageway with the royal Château d’Amboise, for the distance between the palaces was only five hundred meters. François, who was educated in the best traditions of Renaissance humanism and had an innate propensity for the arts, dreaming to make France a great cultural European center, frequently visited Leonardo through this tunnel, having spent hours with the Maestro engaged in intellectual discourses.

The Valois monarch could spend a great deal of time talking with Maestro Da Vinci about the arts and basic principles of sciences. Despite his stellar education and his nature of a true erudite, François was a humanist and an art-loving soul, and, hence, it must have been somewhat difficult for him to understand things from mechanics and engineering. According to the memoirs kept by descendants of some noble who watched François and Leonardo together, most of their conversations were centered on the arts and Leonardo’s technique in painting called ‘Sfumato’ (a technique that produces soft, imperceptible transitions between colors and tones), which is shown exceptionally well in the face of Mona Lisa, particularly in the shading around her eyes.

Although Maestro Da Vinci is rarely thought of as a philosopher now, his contemporaries viewed him in this light. Leonardo adored the world and human beings as deeply as he studied them, and so most of his works now symbolize this philosophy. He and François were both passionate about the Renaissance and everything progressive, artistic, scientific, and philosophical. Even if François did not understand some principles, fundamentals, or inventions of the artist’s creative science, which Leonardo explained to him, they still had many topics for discussion. In several private conversations, some of which were witnessed by others, François called Leonardo ‘his father’ in the sense that the artist shaped the king’s artistic universe in many ways.

The Florentine goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, who also worked at the French court for a long time, recounted in his autobiography that King François referred to Leonardo Da Vinci as a ‘very great philosopher’. Cellini said of both François and Da Vinci:

“King François, who was so taken by his {Leonardo’s} great qualities, loved to listen to him talk and was to hardly be ever found apart from him {Leonardo}”.

Leonardo and the King of France discussed the monarch’s ambitious plans to construct new Renaissance châteaux in France in order to display the might and magnificence of the nation, his court, and the Valois ruling dynasty. As an architect, Leonardo invented captivating sites and things in the Loire Valley, one of them being his architectural design of the double helix staircase in Château de Chambord, built on François’ orders, although this cannot be confirmed.

François entrusted Leonardo with organizing the royal celebrations. To entertain his royal friend, Leonardo created the large mechanical lion on occasion. When the ruler struck the lion’s body, it released lilies and other flowers falling in a waterfall of color to his feet. François must have been elated and laughed merrily and cordially, having commended the Maestro. Leonardo was not only an artist and a scientist ahead of his time, but also a man whom we would now call a fabulous stage director who knew how to please an audience. Da Vinci’s original automaton is lost, but the animal was recreated at Château du Clos Luce and is now on display there.

As his health continued declining steadily, Leonardo made his will in April 1519, wishing to be buried in France in the Church of St Florentine at Amboise. He bequeathed most of his possessions to his servants and his pupils, who lived with him in France. Leonardo passed away on the 2nd of May 1519 at the age of 67, presumably of heart stroke. Francesco Melzi received his books, sketches, painting supplies, and paintings, while Salai inherited half of his garden with a home in Milan. Yet, according to records of 1525, Salai possessed some of Leonardo’s paintings, including the Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist. King François purchased the Mona Lisa from Salai and kept it at his favorite Château de Fontainebleau, until much later King Louis XIV took it to Versailles. Nowadays, this legendary artwork is in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

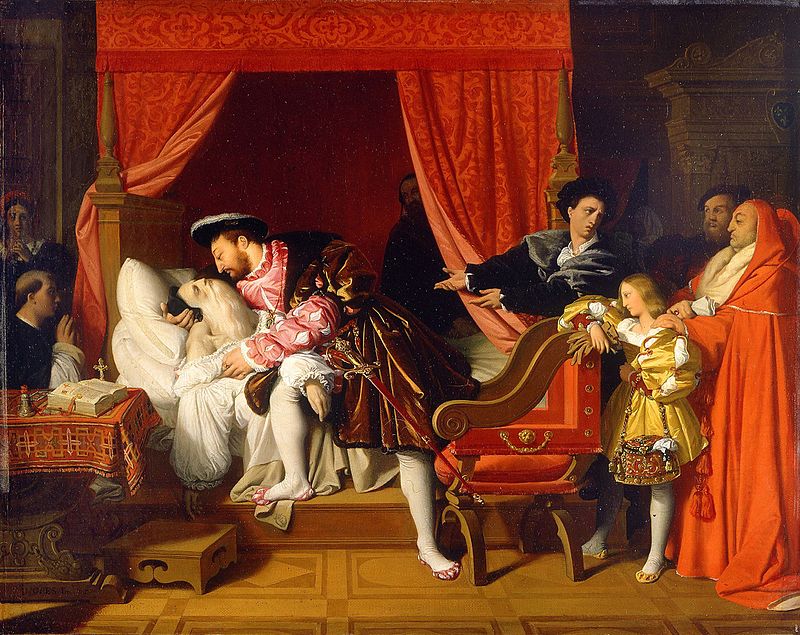

There is a popular and sweet legend that Leonardo Da Vinci died in the arms of François I. According to this legend, when the monarch once visited his favorite artist, he found Leonardo bedridden and dying. A distraught François settled himself on the edge of the bed and wrapped his arm about Leonardo, who said something to him and then died peacefully. Nevertheless, it seems to be only a legend based on the fact of friendship between the Maestro and the king. It is documented that François openly wept upon hearing of Leonardo’s death.

His last wish granted, Leonardo Da Vinci was interred in the Church of St Florentin in Amboise on the 12th of August 1519. Nonetheless, centuries later, the church was demolished during the French Revolution in the late 18th century. In 1863, the alleged bones of the Maestro Da Vinci were discovered, and then they were moved to the Chapel of Saint-Hubert located in the gardens of Château d’Amboise. At present, Leonardo’s tomb is situated on the left side of the chapel: it is a simple granite grave with a bronze medallion that represents the scientist’s profile, and there are two epitaphs on the wall, in French and in Italian, describing his birth, death, and how the Florentine genius came to rest in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert.

In French, this epitaph sounds like this:

“Leonardo da Vinci, who was born in Vinci the 14th of April 1452, spent the last 3 years of his life in Amboise, in the castle of Clos-Lucé, invited by King François I. Leonardo died here the 2nd of May 1519. He was buried, as he asked, in the St Florentin church, which was destroyed in 1807. His remains, which were found during the excavations in 1863, were transferred to this chapel.”

Leonardo’s last years were quiet and yet satisfactory ones in France, where he lived in luxury thanks to the benevolence and generosity of King François I of France. Despite his relatively short stay in France (only three years), Maestro Da Vinci had a profound influence upon the culture of the realm and left Frenchmen invaluable masterpieces such as ‘the Mona Lisa’, ‘The Virgin and Child with St. Anne’, and ‘St. John the Baptist.’

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville