Today is a day of mourning for historians and Tudor enthusiasts. On the early morning of the 17th of May 1536, several men, among them the queen’s own brother, were escorted out of the western entrance of the Tower under heavy guard. They were George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford, as well as Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, Sir William Brereton, and Mark Smeaton.

They must all have been fully resigned to their fates, waiting for death to be released from their sufferings, inflicted upon them by King Henry and Thomas Cromwell. Relief must have washed over them at the knowledge that their sentences had been commuted to beheading, for they could have been hanged, drawn, and quartered. Perhaps they were granted a more merciful death because Cromwell feared to enrage the crowds prior to the more important day – the execution of Anne Boleyn, for there was discontent among some Londoners because of these events.

Large crowds had assembled on Tower Green to watch the bloody spectacle – the execution of those men who had once been favored by His Majesty and held power at the royal court. Among them, there must have been many enemies of the Boleyns, who had come to gloat, some of them supporters of the bastardized princess, Mary Tudor, and of the late Queen Catherine of Aragon.

As the highest-ranked man among the condemned prisoners, George Boleyn was the first one to climb the scaffold and meet his maker. According to the Chronicles of Calais in the Reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII to the year 1540, George pronounced the following speech:

“Christian men, I am born under the law, and judged under the law, and die under the law, and the law hath condemned me. Masters all, I am not come hither for to preach, but for to die, for I have deserved to died if had 20 lives, more shamefully than can be devised, for I am a wretched sinner, and I have sinned shamefully.

I have known no man so evil, and to rehearse my sins openly it were no pleasure to you to hear them, nor yet for me to rehearse them, for God knoweth all. Therefore, masters all, I pray you take heed by me, and especially my lords and gentlemen of the court, the which I have been among, take heed by me and beware of such a fall. And I pray to God the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, three persons and one God, that my death may be an example to you all. And beware, trust not in the vanity of the world, and especially in the flattering of the court.

And I cry God mercy, and ask all the world forgiveness, as willingly as I would have forgiveness of God; and if I have offended any man that is not here how, either in thought, word or deed, and if you hear any such, I pray you heartily on my behalf, pray them to forgive me for God’s sake. And yet, my masters all, I have one thing for to say to you, men do come and say that I have been a setter forth of the word of God, and one that have favoured the Gospel of Christ; and because I would not that God’s word should be slandered by me, I say unto you all, that if I had followed God’s word in deed as I did read it and set it forth to my power, I had not come to this. I did read the Gospel of Christ, but I did not follow it; if I had, I had been a living man among you: therefore I pray you, masters all, for God’s sake stick to the truth and follow it, for one good follower is worth three readers, as God knoweth.”

George’s speech was both conventional and dramatic. He chose a form of speech traditional for executions: he acknowledged that he had been condemned by the law and, hence, merited death because he was a sinner. Well, all people are sinners in different ways, and this cannot be viewed as a hint at George’s homosexual nature, as it was shown in the Showtime’s ‘The Tudors’. This is not true: we do not know whether George loved his wife, Jane Boleyn, or not, but he was not a gay. His speech also contained a sermon to the crowd, warning them about sinning and urging them to learn from his mistakes and missteps. This was truly an emotionally gripping moment!

After the speech, George bravely knelt at the block. He was beheaded with one clean strike of the executioner’s axe. The young, talented man – a Tudor courtier, poet, and diplomat famous for his attractive appearance, intelligence, and his reformed religious views – was murdered.

Norris, Weston, Brereton, and Smeaton soon followed George. It is difficult to imagine what they must have been thinking and feeling, save their relief that their ordeals would be over. As George had been killed before them, the scaffold was bloodied, and the fear of the other men could have mounted to a significant degree. Were they still all loyal to the King of England? It is impossible to give the true answer, but they knew that they were innocent and were never Anne’s lovers, which must have shaken their fealty to their tyrannical and mercurial sovereign.

According to Thomas Wyatt, Sir Francis Weston declared at his execution:

“I had thought to have lived in abomination yet this twenty or thirty years and then to have made amends. I thought little it would come to this.”

Based on what Wyatt reported, Sir Henry Norris “sayed almost nothinge at all” and simply died, while and that Sir William Brereton communicated something like:

“I have deserved to die if it were a thousand deaths. But the cause whereof I die, judge not. But if ye judge, judge the best.”

Mark Smeaton was the final man to be killed. It must have been dreadful to stand on the scaffold littered with mutilated corpses of those whom he had once known and been friends with. Yet, he was fortunate: as a man of lower class than the others, he could have ended his life in a far more atrocious way by being hanged, drawn, and quartered, so to leave this world by beheading with the axe was preferable for him. Unfortunately, Smeaton did not retract the confession of his false adultery with Anne. Perhaps he deserved death, but definitely not for sleeping with the queen. I wonder whether Smeaton had qualms of conscience when he merely declared before dying:

“Masters, I pray you all pray for me for I have deserved death.”

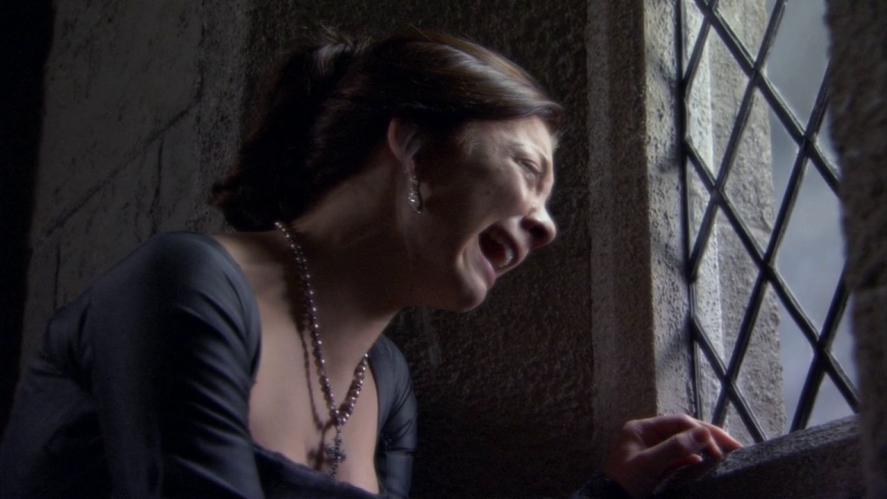

At the same time, inside the Tower, Anne’s soul was writhing in the throes of mental agony, knowing that her brother was dying. Her consolation must have been that their sentences had been commuted to beheading, which had given them quicker deaths. This is a tragic legend or belief that Anne could have witnessed the execution of George and the others from the window of her cell. In the Showtime’s ‘The Tudors’ (2007-2010) the audience may watch the dramatic scene of a heartbroken Anne witnessing the gruesome executions, and I like this episode a lot, for it is a heart-wrenching and yet beautiful in its tragedy scene from Anne’s last days.

Nonetheless, Anne was incarcerated in the Queen’s Lodgings in the south-east corner of the Tower – the same rooms where she had spent the night before her coronation. To make it possible for her to watch these executions, she must have been moved to some room located on the north or west side of the Tower. Did the Tower officials have any reason to alter Anne’s location? It is highly unlikely that they would have done so. At the same time, there is tradition that Thomas Wyatt, a famous poet, could have watched the executions from his prison in the Bell Tower, which sounds more realistic given the location of his cell where he was detained in May 1536.

Having met their gruesome deaths with dignity, the men’s corpses were taken away from the scaffold. As Henry Norris, Mark Smeaton, William Brereton, and Francis Weston were commoners, they were buried in the churchyard of the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. On this occasion, George was more fortunate: as he was a nobleman, his head and his other remains were taken inside the Chapel, and interred in the chancel area before the high altar.

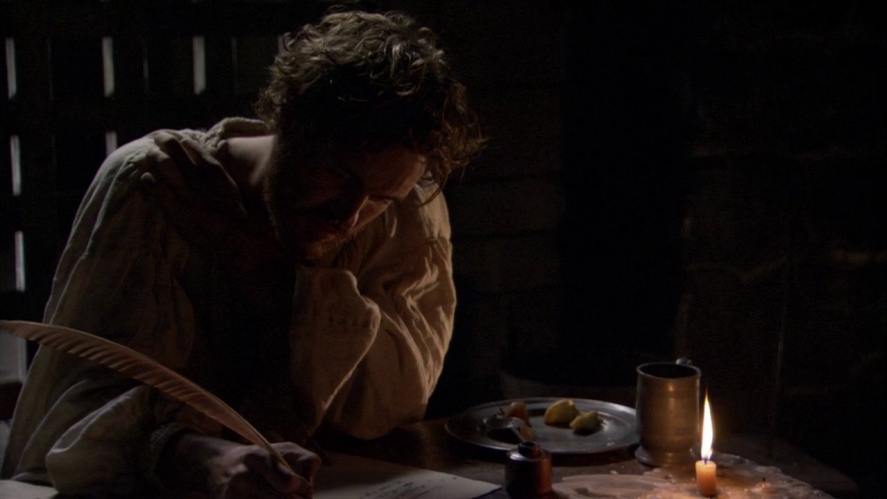

Thomas Wyatt could have seen the executions from his cell in the Bell Tower. Deeply affected by the royal injustice and the committed cruelties, the poet later composed his famous poem called in Latin ‘Circumdederunt me intimici me’ (‘My enemies have surrounded me’):

Who list his wealth and ease retain,

Himself let him unknown contain.

Press not too fast in at that gate

Where the return stands by disdain,

For sure, circa Regna tonat.

The high mountains are blasted oft

When the low valley is mild and soft.

Fortune with Health stands at debate;

The fall is grievous from aloft,

And sure, circa Regna tonat.

These bloody days have broken my heart.

My lust, my youth did them depart,

And blind desire of estate.

Who hastes to climb seeks to revert.

Of truth, circa Regna tonat.

The Bell Tower showed me such sight

That in my head sticks day and night.

There did I lean out of a grate,

For all favour, glory, or might,

That yet circa Regna tonat.

By proof, I say, there did I learn:

Wit helpeth not defence too yern [eager],

Of innocency to plead or prate.

Bear low, therefore, give God the stern,

For sure, circa Regna tonat.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville