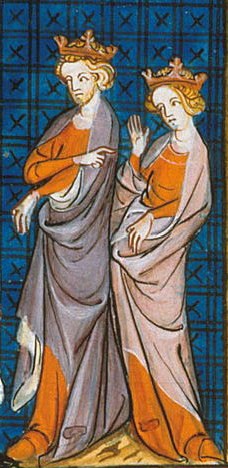

Today marks another anniversary of a royal marriage that helped create the vast and once very powerful Angevin Empire. On the 18th of May, 1152, Henry Plantagenet, also known as Henry Curtmantle and Henry FitzEmpress who would soon become King Henry II of England, married Eleanor (Aliénor) of Aquitaine in a private ceremony in Poitiers. Fate could not have connected two more strong, intelligent, attractive, and energetic people than Henry and Eleanor, despite their eleven-year age gap.

Eleanor’s biographer Marion Meade wrote of her personality:

“Although Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of France and later of England, lived at a time when women as individuals had few significant rights, she was nevertheless the key political figure of the twelfth century. At the age of

fifteen she inherited one-quarter of modern-day France, but since women were thought unfit to rule, her land as well as her person were delegated to the custody of men.”

In 1137, Eleanor, having inherited her father Duke William of Aquitaine’s enormous estates and wealth, had married King Louis VII of France in her teens in the Cathedral of Saint-André in Bordeaux. During their long marriage, the spouses were unhappy due to the substantial differences of their personalities. She had birthed Louis two daughters, had done on Crusade with him, and played a leading role in their relationship. However, Eleanor had failed in her main duty – she had not given Louis a male heir. It was the main reason why they had proceeded to an annulment.

In Eleanor’s lifetime, there had been a widespread opinion that Louis could have had repudiated her on the grounds of her adultery, but this cannot be proved. They had decided that the annulment would happen because of consanguity. On the 21st of March, 1152, Eleanor had arrived at the royal castle of Beaugency, located near Orléans. A large assembly had gathered there, and after confirmations of the clauses they had agreed upon, the witnesses had confirmed that the spouses were related within the prohibited degree. After Eleanor had been promised to obtain all of her lands back, the annulment was finally pronounced.

It seems that Eleanor and Louis parted on relatively cordial terms, and they would never see each other again. Eleanor and her escort rode away from Beaugency shortly afterwards. A new life was dawning upon her, and she was elated to leave the king who did not attract her as a man and a person. The annulment had given Eleanor back Aquitaine and Poitou. The news of her freedom had spread like wildfire, and people had lined up along the roads, smiling and waving at her.

Upon her arrival in the city of Blois, an exhilarated Eleanor had learned that Theobald of Blois, second son of Louis’ vassal and Count of Champagne, had plotted to abduct her. A scared Eleanor had been quickly escorted to Tourane, which belonged to Henry Plantagenet and where she could have been in more safety. Nearing the River Creuse, she had received more alarming news that Henry’s younger brother – Geoffrey, Count of Nantes, known as Geoffrey of Anjou and Geoffrey FitzEmpress – had organized an ambush at Port-de-Piles to entrap her. The hunt on the former Queen of France to marry her and claim her lands had been unprecedented.

Having altered her route, Eleanor had evaded all the traps and safely returned to her beloved Poitiers. Her emotions must have alternated between intense anger, visceral fright, and even some unusually pleasant sensations, despite the danger that these potential abductions posed to her. She was a divorced former queen, who was exceedingly rich and yet single, but the persistent rumor that the King of France had repudiated her because of her empty womb, had damaged her reputation. It had been both a little flattering and frightening that younger lords were interested in her.

After a series of lavish festivities in her favorite Maubergeonne Tower at her Palace of Poitiers, Eleanor had started her life afresh. On her orders, a new household had been assembled, and new clerks had been hired, who had sent many letters and charters to her vassals apprising them of her divorce and demanding that they perform acts of homage and swear fealty to Eleanor, some of them for a second time, as the Countess of Poitou and the Duchess of Aquitaine. At her behest, grants and privileges had been either renewed or withdrawn for abbots and abbesses. One of Eleanor’s main goals was to eliminate French influence from Aquitaine’s life.

During the early days spent home, Eleanor was involved in substantial administrative work. Nothing suggests that she had been preparing to enter into matrimony with Henry, and there is no information about any arrangements for their wedding. All their communications must have been secret, and the story of their romance is shrouded in mystery. Eleanor had invited Henry to Poitiers together with his retinue. In her capacity as Duchess of Aquitaine, she had been obligated to receive Louis’ approval of her new marriage, but she did not.

At the time of Eleanor’s wedding to Henry, only about a few weeks had elapsed since the annulment of her marriage to Louis. The celebration of their wedding was unusual: quiet, almost subdued, and not opulent in the slightest. No trumpets and cannons signaled the second marriage of the duchess, which had been witnessed only by close friends, family, and household members. Perhaps their caution is explained by the fact that Henry and Eleanor did not wish to give their enemies and Louis of France the chance to ruin their marriage plans.

The precautions were taken to ensure the validity of the union. Although her first marriage had been nullified on the ground of consanguity, in fact Eleanor was more closely related to Henry than Louis. She and Henry were half third cousins through their common ancestor Ermengarde of Anjou (wife of Robert I, Duke of Burgundy and Geoffrey, Count of Gâtinais). Moreover, the couple were both descendants of Robert II, Duke of Normandy. Thus, the local bishops swiftly issued the proper dispensations on the orders of the new duke and his duchess.

Not tall, but strongly built man of leonine appearance, Henry was attractive and somewhat freckled, his head full of red hair. He possessed ebullient energy, outspokenness, and an intemperate character, which matched Eleanor’s own energetic nature perfectly. Eleanor and Henry were both intelligent and superbly educated; Matilda and Geoffrey, Henry’s patents, had ensured that their eldest son had received a princely education. During the early days of their marriage, Eleanor concluded that Henry was a complex man with a multitude of contradictory qualities, but he was far more compatible with her than the weak-willed Louis, who was inclined to simple, almost monastic life.

Marion Meade assessed Eleanor’s first impression about her new husband:

“Although Henry thought troubadours and games of chivalry a waste of time, he was not, Eleanor discovered, without refined tastes. His mother had taught him how to behave like a gentleman, and he was capable of great gentleness, courtesy, and at times even delicacy.”

Despite their mutual attraction, Eleanor noticed that Henry was slightly bowlegged. He claimed that he had a natural predisposition to corpulence, so he was always dieting, fasting, or exercised a lot. As custom dictated, the spouses both attended Mass every day, but Henry did so more out of duty than real piety. From the start, Henry began showing his great abilities of an administrator as he gladly engaged in talks with his own advisors and his wife’s officials from Aquitaine. Henry often worked through the night, not wasting a minute, always busy.

Henry’s formidable temper was also apparent. To Eleanor, who was a refined woman with exceptionally courteous manners, hearing her husband rebuke his clerks and pages, and swearing his favorite oath “By the eyes of God!” was a signal that this nineteen-year-old man was not a boy to be trifled with. If she had wanted to marry a younger man to govern his life and dominate, she must have quickly realized her mistake. Furthermore, Henry’s behavior indicated that he had far bigger things on his mind, and that he was not head over heels in love with Eleanor.

Their marriage took the whole of Europe by surprise. It enraged Louis VII of France: neither party had asked his consent, which he would have refused to grant. There was gossip that Eleanor had known carnally the bridegroom’s late father, Geoffrey of Anjou, but this cannot be proved. Some of Henry’s contemporaries said that the Plantagenets were descended from the Devil, and the family members, including Henry, delighted to encourage this tale. Eleanor brought Aquitaine and Poitou to their new realm, and together the couple created a marital alliance with mighty and far-reaching consequences in many years to come.

By Olivia Longueville, copyright 2020

All images are in the public domain.