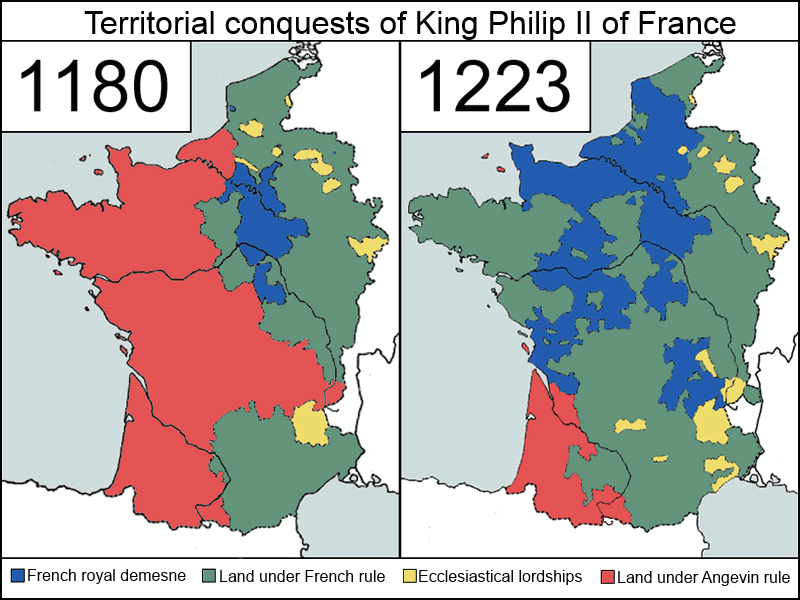

Born on the 21st of August 1165, King Philippe II of France died on the 14th of July 1223 in Mantes-la-Jolie en route to Paris at the age of 58. When his father, Louis VII of France, fell ill, he had his only son crowned at Reims in 1179, making Philippe his co-king. Crowning male heirs during the lifetime of their fathers was a common practice in the early Middle Ages. After Louis’ death in 1180, Philippe started ruling on his own. Originally nicknamed Dieudonné (God-given) because of him being a son born late in his father’s life, Philippe later earned the epithet ‘Augustus’ by the chronicler Rigord for expanding the lands of France tremendously.

After his father’s death, Philippe struggled with the Champagne faction that consisted of his uncles – Henry I, Count of Champagne, Archbishop Guillaume of Reims, and Thibaut V, Count of Blois and Chartres. Given Philippe’s youth, they hoped to control the King of France. In order to get rid of their influence, Philippe entered into matrimony with Isabella, daughter of Baldwin V of Hainaut and niece of Philippe of Alsace, Count of Flanders, who brought the county of Artois as her dowry. The marriage took place in April 1180, much to the unhappiness of the king’s mother, Adela of Champagne, and all of his three uncles because they lost a lot of power.

In 1187, Isabella of Hainaut birthed Philippe’s son, the future King Louis VIII of France. The queen was popular, although she had initially failed to win her husband’s affections due to the lack of her pregnancy during the first 7 years of their matrimony. Later Philippe warmed up to her, and when she passed away in 1190 because of her difficult second pregnancy with twins who also died after their birth, he was grief-stricken. In 3 years, Philippe married Ingeborg, daughter of King Valdemar I of Denmark, in 1193, but he repudiated her after the wedding night due to her supposedly bad breathe. When Ingeborg protested, Philippe had her confined to a convent and appealed to Pope Celestine III for an annulment on the grounds of non-consummation.

Despite my adoration for this highly capable monarch, Philippe’s treatment of Ingeborg was awful. Why did Philippe marry her? Most likely, he strove to obtain more allies against the Angevin dynasty and to get the right to any remaining claims Denmark had to the throne of England. The unfortunate woman insisted that she and Philippe had been intimate. To counter this, Philippe’s advisors created a faux ancestry tree to show that the king and his wife were related, implying that the union should be declared null and void because of consanguinity. However, the Franco-Danish churchman William of Paris defended Ingeborg and drew up a genealogy of the Danish kings, proving that they were not related. In spite of this, Philippe selected Margaret of Geneva (daughter of William I, Count of Geneva) as a new queen, but on the way to France his prospective bride was kidnapped by Count Thomas of Savoy, who married her himself.

Philippe finally married Agnes of Merania from Dalmatia in June 1196. Nevertheless, the new Pope Innocent III declared his union with Agnes invalid, ordering him to return to Ingeborg, but the monarch ignored it. Together Agnes and Philippe had two children – Marie and Philippe, Count of Clermont. The Pope placed France and her ruler under interdict in 1199, which continued until September 1200. Given the above and the pressure from the Danish monarchy, Philippe sent Agnes away and took Ingeborg back as his wife. However, Ingeborg was not treated as queen and lived in some convent, but in 1201, already after Agnes’ death, Philippe again asked the Pope to have his marriage annulled, this time claiming that Ingeborg bewitched him and by doing so, made him incapable to perform his conjugal duties. The Pope rejected his request again.

Philippe reconciled with Ingeborg in 1213 to press his claims to the throne of England through his ties to the Danish crown (the French invasion of England in 1214 didn’t happen). How did Philippe who had such marital problems looked like? There is only one description of him:

“A handsome, strapping fellow, bald but with a cheerful face of ruddy complexion, and a temperament much inclined towards good-living, wine, and women. He was generous to his friends, stingy towards those who displeased him, well-versed in the art of stratagem, orthodox in belief, prudent and stubborn in his resolves. He made judgements with great speed and exactitude. Fortune’s favorite, fearful for his life, easily excited and easily placated, he was very tough with powerful men who resisted him, and took pleasure in provoking discord among them. Never, however, did he cause an adversary to die in prison. He liked to employ humble men, to be the subduer of the proud, the defender of the Church, and feeder of the poor”.

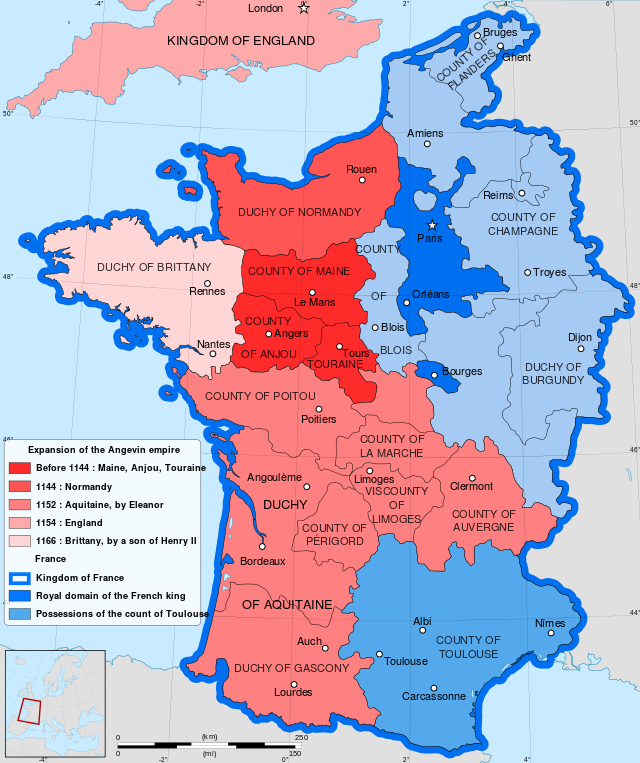

Not a good husband to Ingeborg while loving Merania, Philippe was a crafty and brilliant politician who possessed great skills of logical and strategic thinking. For him every move and decision in politics was like making a new move in the game of chess. From the very beginning, Philippe dreamed of diminishing the Angevin territorial presence on the continent, and to accomplish this objective, he gambled hard. King Henry II of England’s Angevin empire included Normandy, Maine, Anjou, and Touraine, with Aquitaine in the hands of his son, Richard, and Brittany ruled by his another son, Geoffrey, who died in 1186. Philippe considered his neighbors enemies, in addition to having old disputes with them over the counties of Vexin, Berry, and Auvergne.

Cleverly using the frictions between Henry and his sons, Philippe easily and often switched sides. When Henry arrived in Normandy in 1180 to ally with the House of Champagne, Philippe persuaded him to sign the Treaty of Gisors, politically isolating his uncles. When in later years the rift between Henry and Richard widened, Philippe exploited this and allied with Richard who voluntarily paid homage to him at Bonmoulins in 1188. After a short confrontation, the aging King of England was forced to renew his own homage in accordance with the Treaty of Azay-le-Rideau signed in July 1189, in which Henry consented to cede to France Issoudun and Graçay and to renounce his claims to Auvergne. Henry died 2 days later, and Richard succeeded him.

Richard and Philippe together proceeded to go on the Third Crusade against Sultan Saladin in the Holy Land. Arriving in Palestine, they cooperated against the Muslims during the siege of Acre, which was taken after a few years of unsuccessful attempts to conquer it thanks to Richard’s military genius. Philippe nevertheless fell ill, and using it as a pretext for returning to France, he soon sailed from Acre, leaving Richard with his gold and French knights. At the time, Philippe’s goals were to settle the succession to Flanders as Philippe of Alsace had just passed away on the Crusade, and to start his much-desired conquest of Normandy. By the end of 1191, Philippe was back in France that had been ruled by his mother, Adela, as his regent during his absence.

Philippe attacked Richard’s possessions in his absence. Fortunately for the King of France Richard was taken prisoner while on his way back by Duke Leopold V of Austria. During the English ruler’s captivity, Philippe did his best to prolong it and conspired with Richard’s younger brother – John, Count of Mortain. After Richard’s release in 1194, the Lionheart began waging war against Philippe and reconciled with his brother. Because of Richard’s military talents, the French troops were defeated in a series of campaigns between 1194 and 1198. Perhaps Philippe’s dream to dismantle the Angevin Empire would not have materialized, but fate intervened – the Lionheart was shot in the shoulder with a crossbow bolt while inspecting the besieged castle at Châlus-Chabrol and died due to his gangrenous wound on the 6th of April 1199.

King John of England was neither a formidable warrior and tactician nor a brilliant politician, so Philippe must have rejoiced in his ascension. At first, Philippe used the fact that John’s right to the throne could be contested by Arthur of Brittany, the son of John’s late elder brother Geoffrey. However, later it became more beneficial for France to come to terms with John by signing the Treaty of Le Goulet of 1200. Desperate to gain Philippe’s recognition of him as Richard’s heir, John ceded Évreux and Vexin to France, and he agreed that Issoudun and Graçay would be the dowry of his niece Blanche of Castile, who was to marry Philippe’s son Louis. John renounced any claim to Berry and Auvergne. It was Philippe’s victory!

When Philippe summoned John to pay homage to him in 1202, his English counterpart didn’t come, which allowed Philippe to resume his campaign against the Angevins. The French overran most of Normandy, while Arthur of Brittany battled against John’s supporters in Poitou. The Duke of Brittany besieged his own grandmother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, in Château de Mirebeau, forcing John to march on Mirebeau and, taking Arthur by surprise, defeat and capture the hotheaded youth in July 1202. Then Arthur was probably murdered sometime in 1203. Perhaps Philippe, who was quite a forward-looking man, predicted that in the struggle between John and young Arthur, John would eventually prevail, so he dropped his support for Arthur.

After his quick conquest of Normandy, Philippe subdued Maine, Touraine, Anjou, and most of Poitou between 1204 and 1205. The King of France prudently strove to secure his conquests in a legal way: the crafty Philippe demanded that John appear before the Court of the Peers of France to answer for the murder of Arthur of Brittany, but his English rival didn’t appear, fearing for his life and freedom. In response, Philippe officially dispossessed the English of all the continental lands. In 1206, John and his army disembarked in La Rochelle, but the French crushed the English. Later Philippe sought to secure his power in the conquered lands by lavishing privileges on the towns and on the religious houses, leaving all of the local lords in power.

Later, Philippe endeavored to exploit the dispute between John and Pope Innocent III who excommunicated the English ruler in 1209. Philippe and his son, Louis, began preparing for an invasion of England. Philippe had to drop these plans after John settled his dispute with the Pope in 1213. To avenge the losses of his ancestral lands and try to reclaim them, John formed a coalition against France: the Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV, Count Ferdinand of Flanders, and Renaud de Dammartin, Count of Boulogne. The allies invaded the new Capetian territory from the northeast, while John attacked from the west with the aid of his Poitevin barons.

Fate smiled upon Philippe: his troops utterly defeated the allied army, commanded by Otto IV, at the Battle of Bouvines on the 27th of July 1214. The King of France emerged triumphant from the main confrontation of his life, taking prisoner the Count of Flanders and the Count of Boulogne. The wounded Otto was carried away from the battlefield and later fled from France. At the same time, John retreated back to La Rochelle and soon returned to England. Philippe’s victory at Bouvines meant the collapse of the Anglo-Angevin power in France and marked the beginning of a new era for France that became one of the most powerful European countries.

Philippe’s main accomplishment is the unprecedented enlargement of his realm through his conquests. He then acquired Vermandois and Valois. The French invasion of England eventually happened in 1216 when the English rebellious barons invited Prince Louis to be their monarch, but Philippe’s son was excommunicated, and the operation was unsuccessful. Generous fate gave the King of France the former Angevin lands, while fairly keeping England independent from France. The annexation of eastern Languedoc happened after Philippe’s death.

Philippe handled the French nobility very successfully. He subdued all of his vassals and had excellent relations with the French clergy even when the king was excommunicated. He prudently left the canons of the cathedral chapters free to elect their bishops and supported the monastic orders. The monarch won the support of the towns, including those in the conquered domains, by granting privileges and liberties to merchants and aiding their struggles to liberate themselves from the nobles’ authority. In return, the towns were generous to the French Crown, supplying Philippe’s coffers with money and his armies with soldiers. The ruler maintained the balance of power between the Church and the powerful lords of his realm.

Philippe paid much attention to the capital of France. Paris was refortified with ramparts, the thoroughfares were paved, and the new walls were built around the city. The central market, Les Halles, was created, and the construction of Notre-Dame de Paris, which had begun during the reign of Louis VII, continued. The king constructed the Palais du Louvre as a fortress that would be rebuild several times in later centuries. Philippe contributed a lot to education: he gave a charter to the University of Paris in 1200 and conferred special privileges on students and teachers.

The French people, who loved Philippe II of France dearly, lamented when the news of his death broke out. On his deathbed, Philippe asked his son, Louis, to treat Ingeborg well, and she outlived him by 14 years. Despite his marital problems and the fact that he was not always honorable, Philippe deserves to be called ‘Augustus’, for he was one of the best French monarchs who loved his country, gained lots of new territories, and shaped modern France in many ways.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville