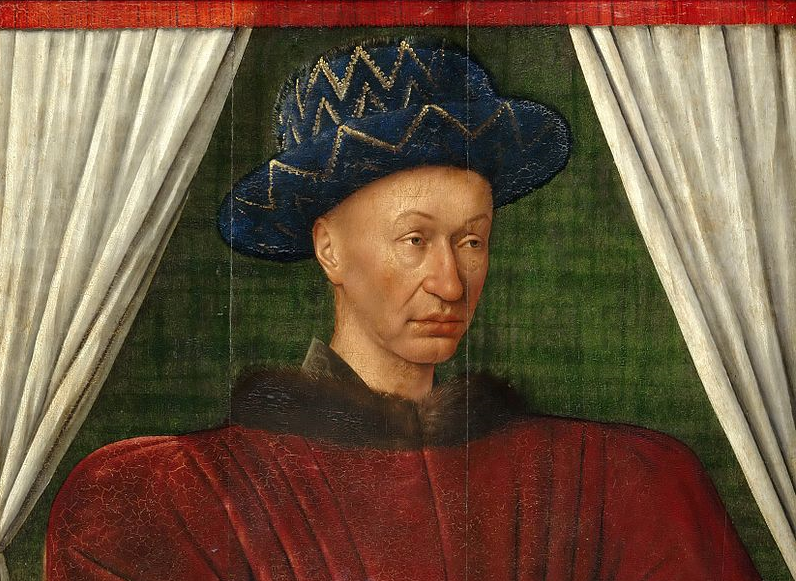

King Charles VII of France, known as the Victorious (le Victorieux), died on the 22nd of July, 1461 at Mehun-sur-Yèvre at the age of 58. His main legacy is the freedom of the French and the end of the Hundred Years’ War. Nonetheless, Charles VII’s reign started in the atmosphere of utter hopelessness and despair. According to the Treaty of Troyes of 1420 signed in 5 years after the Battle of Agincourt that almost crippled France, the mentally ill King Charles VI consented that the English monarch Henry V was recognized as his heir to the French throne and married Charles VI’s daughter, Catherine de Valois, as well as act as France’s regent.

Charles was born at the Hôtel Saint-Pol, the royal residence in Paris, on the 22nd of February 1403. His parents were King Charles VI of France, known as the Mad, and his highly controversial wife, Isabeau of Bavaria. Charles VI, known as the Beloved or the Mad, lost his touch with reality to such a huge extent that he believed he was made of glass and needed protection from breaking. Charles, a prince back then, was their eleventh child and their fifth son! As no one expected him to succeed his father, he received the title of Count de Ponthieu at his birth. However, the wheel of fate turned in his favor: all of his elder brothers predeceased him childless, and suddenly Charles became the Dauphin of France in 1417. Thus, he inherited all of their titles.

Inspired by his new position, Charles decided to try himself in war. He attacked the English with his armies and besieged Chartres, showcasing his flamboyant commanding style. However, upon learning that Henry V of England intended to launch a counterattack with a much stronger army, Charles fled to the Loire Valley in fear of being defeated. Even in youth, Charles was a clever politician: knowing that Yolande of Aragon, a daughter of John I of Aragon, supported the French in the war, he fled to her protection and married Yolande’s daughter and his cousin – Marie of Anjou – in April 1422. Actually, Charles was betrothed to Marie since 1413 and knew Yolande even before his flight, and now it was high time to reap the benefits of this marital union.

Yolande of Aragon was more a mother to young Charles than his own mother, Isabeau. In early adolescence, when he had already been engaged to Marie, Yolande had taken Charles from his parents’ court and protected him from all perils, while Isabeau worked against his claims to the French throne and supported France’s “alliance” with England. After the marriage of Charles and Marie had been sanctified, Yolande became strategically and emotionally invested in the fight of the House of Valois for the throne of France. After the arrival of a teenaged girl named Jeanne d’Arc at Chinon, it was Yolande who convinced Charles to allow the girl to join the French army. During the Loire Campaign, Yolanda provided the French armies with support of all kinds.

Half of the country was occupied by the English. Charles was sarcastically called ‘King of Bourges’ because he lived south of the Loire River, where he still had authority and traveled with his court between various castles in the area. Jeanne and other charismatic figures, such as French generals Étienne de Vignolles and Jean Poton de Xaintrailles, led their troops to Orléans and lifted the siege of the city. After the Battle of Patay when the English were crushed, the inhabitants of Reims, who had previously sworn their fealty to the English, switched it to France, and the road to the city was safe to travel for Charles who was then crowned at Reims Cathedral.

Of course, Jeanne’s appearance at Chinon was a turning point for Charles, but Jeanne acted more as a spiritual leader for the French generals, the soldiers whose morale had plummeted since the devastating Battle of Agincourt, and the population of France. At the same time, Yolande had Charles surrounded with competent advisers and servants associated with the House of Anjou. Thanks to Yolande’s political talents, Duke John VI of Brittany broke his alliance with England and shifted his allegiances to France. Jeanne’s grandiose involvement, in the first place spiritual one as she became a vivid symbol of hope for everyone, and Yolande’s political and financial aid, coupled with the efforts of the French commanders, turned a tide of war for Charles.

It was a turbulent time for Charles VII when he learned a lot in both politics and military affairs. Although Charles is often blamed for the afflictions of Jeanne d’Arc whom he supposedly could help after her capture by the Burgundian armies under John of Luxembourg at the siege of Compiègne in 1430, his accomplishments are too remarkable to be underestimated. Moreover, it is controversial whether he could really help Jeanne or not, and even if he had really abandoned the girl to her fate, his achievements overshadow even the poor Jeanne’s martyrdom.

In several years, already after Jeanne’s death, Charles broke the English-Burgundian alliance that had allowed the English to have advantage over the French for a long time, signing the Treaty of Arras in 1435, which established peace between Burgundy and France. This ensured that no prince of the blood acknowledged the English Henry VI as King of France. After the recovery of the city of Paris in 1436, Charles focused on creating a well-organized professional army – the first standing army since ancient Roman times, advancing the artillery and cavalry, as well as siege machines. This allowed the French to conduct the steady reconquest of Normandy in the 1440s.

Most importantly, Charles accomplished what seemed to be the most incredible thing to his contemporaries – he won freedom for his people. During the last 8 years of his life, Charles ruled as a sovereign of France independent from England: after the Battle of Castillon of 1453, the English were expelled from the continent, save Calais. All would have been well if not for Charles’ difficult relationship with the rebellious Dauphin Louis (the future Louis XI) who was at first sent to live in the Dauphiné in southern-eastern France, then ignored all of his father’s summons back to court, and finally escaped to the court of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1456.

Charles VII and his wife, Marie of Aragon, had 14 offspring, but only 5 of them survived into adulthood. One of the reasons for loss of many children could be their close blood relationship and the side effects of inbreeding. Charles and Maria were both great-grandchildren of King Jean II of France and his first wife, Bonne of Bohemia, through the male line, which made them second cousins. The senior Valois line was already rather inbred, except for the marriage of Charles VI to Isabeau of Bavaria, which brought some fresh blood to their children. Yet, Maria was not adored by Charles: he loved his paramour, Agnès Sorel, and had three daughters with her, although after Agnès’ death the ruler took her cousin, Antoinette de Maignelais, as his mistress.

It is interesting that Charles VII was the first monarch to secure the French crown against papal power. The Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges was issued in 1438. It established a General Church Council whose authority was superior to that of the papacy and had to assemble every 10 years. The Sanction decreed that people were elected, not appointed, for ecclesiastical positions, and that no one could appeal to the Vatican from places further than 2 days’ journey from Rome, which meant that few French could do so. The Pope could no longer benefit from bestowing and profiting from benefices. Later, this document would be abolished by Louis XI. In non-military affairs, Charles established the University of Poitiers in 1432, and despite the severe conditions caused by war, his taxation policies were not harmful for his subjects’ financial position.

In 1458, Charles VII became ill: a sore on his leg was not healing, got infected, and resulted in the king’s serious fever. Charles summoned Louis to him from Burgundy, but the dauphin did not come and calmly waited for his father’s death. At least the dying monarch had his another son – Charles, Duke de Berry – by his side for consolation. According to contemporary chronicles, Charles did not die of fever or infection – he starved himself to death, crushed by Louis’ final betrayal. Perhaps it is the dramatization of Charles VII’s final tragedy, but it matters not because the king must have been tormented by Louis’ behavior on his deathbed. Charles VII was then buried beside his parents in Saint-Denis, and a new era began for France.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville