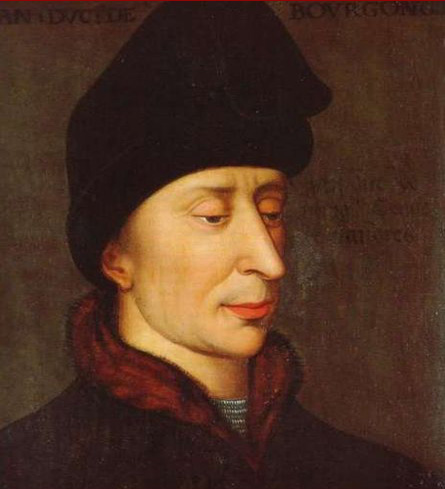

Jean (John) the Fearless (Jean sans Peur) , a member of the Valois Burgundian house, ruled the Duchy of Burgundy from 1404 until his death in 1419. He succeeded his father – Philippe the Bold (le Hardi), who was the youngest son of King Jean II of France and his first wife, Bonne de Luxembourg. Like his father, Jean played an important role in France’s inner affairs during the reign of the mentally unstable King Charles VI of France known as the Mad (le Fou). As the monarch was unable to govern the realm on his own, his several uncles, his younger brother – Louis, Duke d’Orléans – and his wife, Isabeau of Bavaria, struggled for political dominance.

Intemperate, ambitious, ruthless, and amoral, Jean was not a benign and gentle person in the slightest. Accustomed to get what he wanted at any cost, Jean decided to become as influential in France as Philippe the Bold had been. However, he encountered fierce opposition from his smart, handsome, and level-headed cousin – Louis d’Orléans. As he disliked the Burgundian domination at the French court, Louis ejected the Burgundians from both the Privy Council and Paris without any violent measures, and then he started to manage the royal finances by himself. The purchase of the Duchy of Luxembourg by Louis for the French, not Burgundian, House of Valois, was the last straw for Jean, who decided to dispose of the opponent at this point. Philippe the Bold had ruled Burgundy while obtaining half of his income in France, and Louis d’Orléans stopped it, which must have made Jean loathe the man. To accomplish his nefarious goals, Jean recruited the gang of assassins led by Raoulet d’Anquetonville, who served as his henchman.

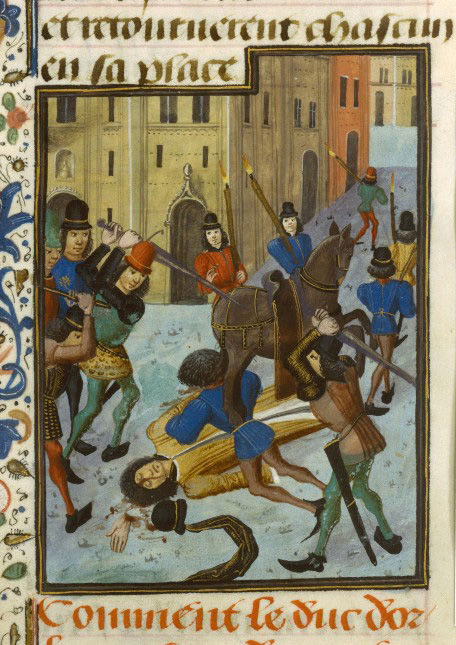

On the tragic evening of the 23th of November 1407, Louis was brutally stabbed by about 15 masked thugs in the streets of Paris while being on his way from Queen Isabeau, whom he had visited at Hôtel Barbette after she had given birth to her son Philippe who died hours after his birth. The valets and others, who endeavored to protect Louis, were all killed, while the duke’s hand was severed and his skull split by an axe. This unprecedented brutality shocked Paris: the royal person – the king’s brother – was killed in the most extreme way. Had Charles VI not been mad, Jean would have been prosecuted and executed without a shadow of a doubt, but Jean quickly seized the opportunity and grabbed the reins of French power into his hands. Jean’s atrocity towards his cousin appears to be the reason why he earned the nickname ‘The Fearless’.

Jean’s crime resulted in the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War in France, which significantly weakened the country and her military potential. Taking advantage of the political chaos in France, King Henry V of England emerged triumphant at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, when the French armies were crippled, although his talent of a general cannot be denied. Following the disaster at Agincourt, Jean and his troops captured Paris, and the royal Hôtel Saint-Pol, which had once been a favorite residence of Charles V of France the Wise (le Sage), drowned in rivers of blood as most of its inhabitants were mercilessly butchered by the Burgundians whose mission was to kill the rest of the Armagnacs on that horrendous night. Jean was successful in taking King Charles VI into his custody, but the teenaged new dauphin (the future Charles VII of France) ran away with the aid of some Armagnacs to Yolande of Aragon’s protection in her castles in the Loire Valley.

Retribution comes when one least expects it. On the 10th of September 1419, Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, met with Dauphin Charles on the bridge at Montereau in the Île-de-France region to have a parley, supposedly for the reconciliation between the Burgundians and the Armagnacs. Most likely, Jean was not inclined to peace, but his finances were in disarray, which could have pushed him to imitate negotiations. How could such a reconciliation be achieved after the atrocities committed by Jean the Fearless, which remained unpunished? The remainder of the Armagnacs all flocked to Dauphin Charles, in whom they saw their leader and the symbol of France’s hope for liberation from the English and the Burgundians. How could Dauphin Charles forget what happened to his uncle Louis and the brutality of the Burgundians when he narrowly escaped death from Hôtel Saint-Pol? How could the dauphin forgive that Jean was negotiating with the English to make King Henry V of England, the victor of Battle of Agincourt, Charles VI’s successor despite the fact that Dauphine Charles was the rightful heir to the Valois throne? Was it possible to forgive Charles’ treacherous mother for her new alliance with the Burgundians?

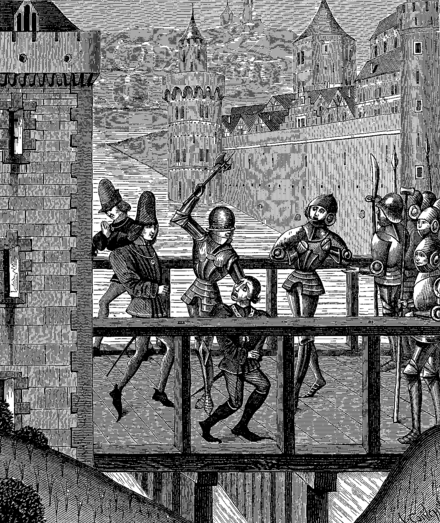

Dauphin Charles and Jean the Fearless, together with their men-at-arms, arrived on the 2 banks of the Seine River, on either side of the bridge of Montereau. Someone told Jean that his life could be in danger, and his men were on high alert. At the same time, Charles was informed about the same by his councilors. Carpenters created two barriers with a door on each side in the middle of the bridge, which served as an enclosure for the meeting. According to their agreements, Charles and Jean had to enter the enclosure, each of them accompanied with 10 loyal people, and then the door had to be closed. The atmosphere was charged with unbearable tension, and demons of premonition sang indecipherable prophesies as the dauphin and the duke finally met.

Jean the Fearless knelt with deference (faux?) before the Dauphin of France, who beheld him with impenetrable eyes. A teenaged Charles, who had witnessed the horrors of the Parisian night when the Armagnacs had been butchered by Jean’s men, must have been horrified to the depths of his soul despite the fact that about a year passed since then. Traumatized by the cruelties, the dauphin seems to have made up his mind to end the Burgundian-Armagnac war once and for all. As he rose from his knees, Jean who must instinctively have felt danger emanating from the young prince, touched the hilt of his sword either for support or preparing for his self-defense. In the next moment, one of the dauphin’s companions, Lord Robert de Loire, asked harshly:

“You put your hand on your épée in the presence of His Highness the Dauphin?”

Everything happened too swiftly, as if a lethal avalanche were sweeping down upon Jean of Burgundy. The Breton knight Tanneguy du Chastel, who was a member of the Armagnac party and was loyal to the true Dauphin of France, delivered an axe blow to the Duke of Burgundy’s face, crying “Kill, kill!” Du Chastel had once served as a henchman of Louis d’Orléans. We don’t know exactly what occurred next, but there was a chaotic struggle between the dauphin’s men and the duke’s entourage which failed to protect Jean. This mêlée had bad consequences for the Burgundians: a slaughtered Jean lay on the ground of the bridge. Later, the Armagnacs all claimed that the murder had been committed in self-defense, but it is unlikely to be entirely true.

Dauphin Charles sent letters to those provinces and cities which kept their allegiance to him that the Almighty punished Duke Jean for his treacherous cooperation with the English and for his lack of action against the enemy. Indeed, Jean and Charles had signed the Treaty of Pouilly-le-Fort, known also under name of Paix du Ponceau (Ponceau from French ‘pont’, or ‘bridge”), when Jean and Charles had attempted to officially reconcile during their previous meeting on a small bridge near Pouilly-le-Fort, not far from Melun. After Jean’s death, Charles referred to this treaty that Jean had breached: according to the document, both the Armagnacs and the Burgundians had to resist ‘the damnable aggressions of the English, our ancient enemies’, but Jean had different intentions. The mad Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria condemned their son for this deed.

Shortly after this event and later in life, Dauphin Charles (Charles VII) always denied that he had known about the planned assassination of his Burgundian cousin in advance, but he was clearly complicit. How could such a young man resort to such brutal measures? Having witnessed the civil war in France and his father’s madness since childhood, Charles was definitely affected by all these traumas. The truth is that Dauphin Charles had many motives to kill Jean the Fearless:

- in revenge for the awful murder of his uncle Duke Louis d’Orléans.

- to punish Jean for his treason to France and the House of Valois because after the capture of Paris, Jean negotiated with the English to make King Henry V of England Charles VI’s heir.

- in vengeance for the possible deaths of his 2 brothers: they were Dauphin Louis of France, also Duke of Guyenne (1397-1415), as well as Dauphin Jean of France, also Duke of Touraine (1398-1417), for Jean was suspected by the Armagnacs as their murderer.

- in revenge for the Parisian massacre of the numerous Armagnacs in 1418 when Dauphin Charles barely fled from the country’s capital to the Loire Valley.

- Charles’ terror that if Jean could have killed his brothers, he could also order to assassinate the dauphin during their parley on the bridge at Montereau.

- to voice Charles’ own political importance by means of committing this political murder and to give a signal to those loyal to the cause of France’s independence from England that they should join forces with the dauphin and the remainder of the Armagnac partisans.

- in self-defense if Jean attempted to kill him (we don’t know it).

- An impulsive decision of Charles and his companions who were full of fear and hatred.

The Armagnacs, all of whom were unequivocally loyal to Charles VI’s son, did themselves quite a damage in French public esteem. Yet, the greatest result was not revenge, but the end of the Burgundian-Armagnac Civil War. Perhaps Charles and his followers indeed believed that only Jean’s death could finish the madness. However, the assassination of Jean the Fearless prompted his son and successor – Philippe the Good (le Bon) – to establish an alliance with the English because of his vengeful motives. Only the Congress of Arras of 1435 between France and Burgundy achieved the final reconciliation between Philippe the Good and King Charles VII, who had already been crowned at Reims Cathedral by that time. According to this document, Philippe acknowledged Charles VII as King of France and his liege lord while being exempted from homage to the Crown. Charles promised to punish the murderers of Jean the Fearless, but he never did so. This treaty was a turning point in the Hundred Years’ War, which would end with the total liberation of France from the invaders. Under Charles VII the Victorious (le Victorieux), France would become united under one monarch for the first time since the Carolingian Emperors, possessing its first standing army, but it is a topic for another article.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville