The Treaty of Arras, signed on the 21st of September 1435, ended the enmity between King Charles VII of France and Philippe the Good, Duke of Burgundy. It was a huge diplomatic victory for Charles VII: his Burgundian cousin finally recognized him as the rightful French monarch. The alliance between the English and Burgundy, which had been established after the murder of Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, was over. As Burgundy was an independent state, whose overlord was formally the ruler of France, Philippe demanded that he be exempted from paying homage to the French Crown, and Charles satisfied his request. They agreed that upon the death of either the monarch or the duke the homage would be resumed. Charles promised to punish the murderers of Philippe’s father – Duke Jean I of Burgundy, or Jean the Fearless.

Burgundy had become allied with the English in 1419. Years ago, on the 10th of September 1419, Jean the Fearless had met with Dauphin Charles (before the Treaty of Troyes of 1420, which disinherited the dauphin) on the bridge at Montereau in the Île-de-France region to have a parley, supposedly for the reconciliation between the Burgundians and the Armagnacs after the long civil war. Jean had been unlikely to want peace, although his finances had been in disarray. Jean had been negotiating with the English to make Henry V of England, the victor of Agincourt, the next French sovereign. Dauphin Charles and Jean the Fearless, accompanied by their men-at-arms, had arrived on the banks of the Seine River. They had met in the middle of the bridge of Montereau, where Jean had been assassinated by the dauphin’s men. This murder had pushed Jean’s son and successor, Philippe the Good, to ally out of vengeful motives with Henry V of England against the Armagnacs and Dauphin Charles.

Shortly after this event and later in life, Charles VII always denied that he had known about the planned assassination of Jean the Fearless in advance, but he was apparently complicit. How could a young man – Charles was only 16 at the time of Jean’s death – resort to such measures? Having witnessed the civil war in France and the insanity of his father – Charles VI known as the Mad (le Fou) – since childhood, Charles was deeply traumatized. The horrors he experienced in his childhood, his adolescence, and his early youth shaped his melancholic, contemplative, and reserved personality. They made Charles cautious and sometimes indecisive despite the inner strength he possessed, for only a strong man could have pulled himself together to dive into an ocean of political intrigues and war despite his difficult situation. Regardless of his rejection of all accusations, Dauphin Charles had many motives to kill Jean the Fearless, including:

- in revenge for the awful murder of his uncle, Duke Louis d’Orléans, in 1407.

- to punish Jean for his treason to France and the House of Valois because after the capture of Paris, Jean negotiated with the English to make King Henry V of England Charles VI’s heir.

- in vengeance for the possible deaths of his 2 brothers: they were Dauphin Louis of France, also Duke of Guyenne (1397-1415), as well as Dauphin Jean of France, also Duke of Touraine (1398-1417). Jean was suspected by the Armagnacs to be their murderer.

- in revenge for the Parisian massacre of the numerous Armagnacs in 1418 when Dauphin Charles narrowly escaped death and fled from the capital to the Loire Valley.

- Charles’ terror that if Jean could have killed his brothers, he could also order to assassinate the dauphin during their parley on the bridge of Montereau.

- to voice Charles’ political importance by means of committing this political murder and to give a signal to those who were loyal to the cause of France’s independence from England that they should join forces with the dauphin and the Armagnac partisans.

- in self-defense if Jean attempted to kill him (we don’t know anything).

- an impulsive decision of Charles and his companions, who were full of fear and hatred.

According to the Treaty of Arras, the political distinction between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians no longer mattered. Nevertheless, Charles VII would never punish any murderer of Jean the Fearless despite his promise, most likely because he could not prosecute himself while also considering the murder of Philippe’s father an equitable retribution for Jean’s own crimes against France and the Valois family. Charles VII abided by all other terms and conditions of the treaty. The end of the family strife allowed King Charles to unite all political factions in his realm.

The Congress of Arras had started on an unfortunate note for England. The English regent – John Plantagenet, Duke of Bedford – had died on the 14th of September 1435. Bedford was Philippe’s ally, and his passing made the Anglo-Burgundian alliance worthless for Philippe from a political standpoint. At first, the English delegation attended the Congress. Their offer was to establish a 20-year truce and cement it with a marriage between young King Henry VI of England (the man was not mentally unstable yet at the time) and a daughter of King Charles VII of France. Nonetheless, the Plantagenets categorically refused to give up the English claim to France, and this was the Gordian knot at the heart of the peace negotiations. As tensions escalated, the English left, but they returned later, only to discover that Philippe the Good switched sides and reconciled with his cousin Charles. It was a black day for the English: it was obvious that the Treaty of Arras was a turning point in the Hundred Years’ War in favor of the French.

English kings believed that they had the right for the French throne after all of the 3 sons of Philippe IV of France known as the Fair (le Bel) had died without any surviving male issue. The last direct Capetian king – Charles IV of France – had breathed his last in 1328. On his maternal side, Edward III of England was descended from Philippe IV of France, his grandfather; Edward’s mother was Isabella of France. In reality, the Frankish Salic law always prevented female succession of French princesses and that of their male descendants, being the remnant of the Merovingian epoch in France. After the House of Capet had gone extinct on the male line in 1328, the throne was inherited by the nearest male relative – Philippe VI of France, the Fair’s nephew. The French nobles never wanted a foreign king to rule their realm. Moreover, the French aristocracy respected Philippe VI’s father – Count Charles de Valois, who had once been Philippe IV’s highly capable councilor. During the Ancien Régime in France, the closest male relative always inherited the throne. The Estates General (États généraux), the nobility, and the commoners would not have allowed to abolish this law. In fact, the Salic law firmly established the order of succession, and in case of its cancellation, many pretenders to the French throne, especially foreign ones, would quickly have appeared. It actuality, the Salic law, which seems a trivial and archaic thing at first glance, defended France from foreign invasions and possible civil wars.

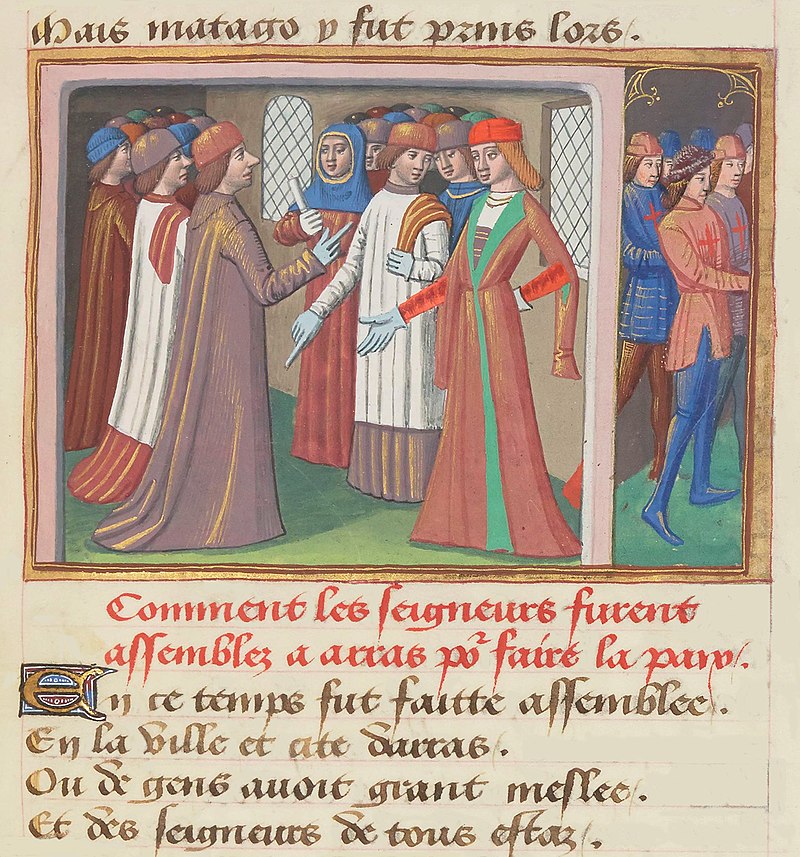

On the 21st of September 1435, the Treaty of Arras was concluded in a ceremony held at the Abbey of St Vaast (a Benedictine monastery in Arras). The cardinals formally absolved Philippe the Good from his oath to the Treaty of Troyes of 1420 and other obligations to the English. The Duke de Bourbon and Arthur de Richemont offered a public apology at the altar on behalf of their king for the murder of the duke’s father, but no punishment would follow. Philippe swore an oath of peace with and fealty to Charles VII. In reward, Philippe the Good received new vassal lands: the Counties of Auxerre and of Boulogne, the cities on the Somme and Péronne, Ponthieu, and Vermandois. Satisfied with such generous terms, Philippe restored the County of Tonnerre to France. Charles promised to establish religious foundations and conduct Masses in Jean’s memory, but it was done only once in Philippe’s presence. The terms of this treaty appeared in many French and Flemish chronicles of the time.

Perhaps starting from this moment, the English chronicles began to portray King Charles VII of France in an unfavorable light on purpose: as a vile murderer of Jean the Fearless who was wrongly said to be an honorable man, as a ladies’ man not caring about his country, and as an indecisive, weak monarch. One of Charles’ portrayals in Anglo-Saxon movies and popular culture is that he was a crafty and unscrupulous dauphin/king, one who was interested in entertainments and women, while Jeanne d’Arc – indeed, a true heroine of France – fought wars for him. First of all, Jeanne became mostly a spiritual symbol that helped unite the French as a nation against the invaders and boosted patriotism in the country. The armies, which won the Loire Campaign of 1429, were commanded by the king’s loyal generals and financed by his mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon – this woman aided Charles to win the Hundred Years’ War. Another myth is that Charles abandoned poor Jeanne to her fate in captivity after she had helped him be crowned at Reims, although he was an enemy of both the Burgundians and the English at the time of her capture. Nevertheless, we can find a few letters in French archieves, in which Charles offered his cousin, Philippe the Good, to ransom Jeanne. The English were on the losing side, so the result was the significant bias towards Charles VII that has survived to this day. History is written by the survivors and the winners, but it is also often rewritten by the losers.

For some contemporaries, the Treaty of Arras could have been a relatively insignificant event, but it had a tremendous importance for France. For the first time in centuries since the fall of the Carolingian empire and and after the fall of several Carolingian states following the division of Charlemagne’s vast realm between his descendants, France was totally united under the rule of her king – Charles VII of France. In years to come, Charles VII would focus on the creation of France’s new professional army that would apply artillery against the invaders and win many battles, just as Edward III and Edward the Black Prince had once used the longbow to defeat the French at Crécy and Poitiers. Those, who blame Charles VII for abandoning Jeanne d’Arc after her capture by the Burgundians and her later transfer into the English custody, should remember that until 1435, Charles was a mortal enemy of the Duke of Burgundy and of the Duke of Bedford. This made it impossible for Charles to arrange Jeanne’s release by paying ransom for her, so the heroine of France was burned at the stake in 1431. It is interesting that after the treaty had been signed, the Isle of Wight and most of the counties along the south coast of England were put on alert against the threat of French invasion, which was bizarre given that Charles VII was only in the middle of his quest to liberate France from the English and, hence, could not be distracted.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville