Marie d’Anjou, who was a daughter of Louis II d’Anjou and his wife, Yolande of Aragon, was born on the 14th of October 1404. Marie was betrothed to Charles de Valois for years: their betrothal agreement had first been signed when he had been the youngest son of Charles VI of France called the Mad (le Fou) and Isabeau of Bavaria, holding the title of Count de Ponthieu, which Charles had received at his birth in 1403. Over time, his elder brothers died, and Charles became the Dauphin of France, whose fate was more difficult than the most complex conundrum. The wedding of Marie and Charles took place on the 18th of December 1422 at Bourges, when he was already King of France, although most of the country was controlled by the English.

Marie and Charles married when France was going through numerous trials and tribulations, and when the country’s fate was hanging in the balance. Charles and Marie were sovereigns of the battered kingdom occupied by the English since the forces of Henry V of England had defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415. Marie’s husband had been outlawed and disinherited as a result of the Treaty of Troyes of 1420, when the insane Charles VI, her father-in-law, convinced by the Burgundians and his treacherous wife, Isabeau, had nearly broken the life of his only surviving son. For a long time, Charles was acridly called the King of Bourges, while Marie was the Queen of Bourges, and their nomadic court, financed only by her mother, Yolande, moved from one castle to another in the Loire Valley. During this time, Charles considered escaping from France with his wife either to Scotland or to Aragon, but Yolande convinced him not to do so.

After their wedding, Marie was not crowned, and she would remain the only Queen of France who was never crowned. Between 1422 and 1429, during the critical part of the Lancastrian stage of the Hundred Years’ War, the situation was France was desperate despite the death of Henry V of England in 1421. His brother and regent for his infant son, Henry VI, – John Plantagenet, Duke of Bedford – was advancing towards the Loire Valley and threatened to conquer the southern lands of France. During this time, Charles VII was crestfallen and often spent time locked in his rooms, staring into space as waves of despair crushed him one after another, like overwhelming tides of blackness. Nonetheless, he regularly performed his marital duties, and Marie was often pregnant: their eldest son Louis, who was destined for kingship, was born in 1423; their son Jean, born in 1426, lived for a few years; Radegonde, born in 1428, died in 1444; and Catherine, born most likely in 1429, also passed away young. Then, in 1429, the situation changed dramatically.

Marie must have witnessed her husband’s sensational meeting with the peasant girl, Jeanne d’Arc, at Château de Chinon, where Jeanne came to inform the Dauphin of France – Charles was not crowned at the time – that her mission was to unite France against the enemy and help him be crowned at Reims Cathedral. Marie was a docile, shy, and very traditional woman who devoted her life to her offspring and to running the court, not to politics, so she is likely not to have been involved in this matter. Some historians believe that Jeanne was introduced to Charles thanks to Yolande of Aragon’s careful and cunning scheming, for the king’s mother-in-law never abandoned Charles and always gave him both moral and financial support in the most difficult moments of his life. I’m inclined to agree with this theory, or at least I think that Yolande could have played her role in this. Marie could have seen Jeanne and even talked to her. The queen must have rejoiced when the Loire campaign against the English turned out to be successful. This campaign was financed by Marie’s mother and was fought by the French generals loyal to King Charles VII, with Jeanne d’Arc serving as a symbol of heroism and unification of France against the foe.

Between 1429 and 1441, Marie d’Anjou continued being a model medieval queen – quiet, obedient, and fertile. Although in modern popular culture we can often see that Charles VII was a carefree philanderer who entertained while Jeanne d’Arc fought for him, this misrepresentation of his personality is a grievous mistake, in most cases done deliberately due to the Anglo-Saxon bias towards this monarch and, sometimes, for dramatic purposes. Unlike her mother, Marie was not a stunning beauty: she was not gorgeous, but the queen had a charming and warm personality that must have been like a balm to Charles’ scarred heart during those years. There is no evidence of Charles’ passionate love for his wife, but there is also no proof that he was a womanizer until he met young Agnès Sorel in the early 1440s. Charles could have had affairs from time to time, perhaps with Marie’s ladies, but he definitely respected his wife. At the same time, Marie was devoted to Charles and the cause of freeing their realm, and without a shadow of a doubt, she supported her spouse in all ways she could. And Charles never forgot about her and regularly came to her bed, which resulted in 8 more children during these years.

Marie was fertile, but most of her large progeny were sickly and weak. Her son, James, who was born in 1432, died at the age of 5. Philippe, born in 1436, and Marguerite, born in 1438, both passed away in infancy. Her 2 other daughters – Yolande (born in 1434) and Jeanne (born in 1435) – survived into adulthood and married. Only Yolande, who was the wife of Amadeus IX, Duke de Savoy, birthed him 10 children and lived a relatively long life according to the standards of the time, dying at the age of 43. In 1438, another tragedy hit Marie and Charles hard: she birthed twin daughters, Jeanne and Marie, but the latter died in infancy and the former breathed her last aged 8. Isabella, born in 1441, died young as well. Charles had been crowned at Reims in 1429, without Marie, who he could not have taken with him because of the danger to be confronted by the English armies which still occupied areas in the vicinity of Reims. Charles had also reconciled with his Burgundian cousin – Philippe the Good, Duke of Burgundy – when they had signed the Treaty of Arras in 1435, and soon Charles VII had entered Paris, the ancient capital of the French realm. Perhaps her husband’s political victories somewhat lessened the pain from the loss of their children. Yet, Marie constantly lived in fear for the lives of her remaining frail offspring.

In her late childbearing years, Marie was lucky: she produced Magdalena in 1443, who was not very sickly, and who later became the Queen of Navarre. Her last child was a boy: Charles, who was at birth Duke de Berry, emerged out of her womb in 1446, but, unfortunately, who years later died young of some malady without any legitimate issue. Despite the loss of many children, Marie fulfilled her wifely duty: she gave Charles VII 2 sons, securing the succession. During all this time, Marie remained at Charles’ side, although they lived separately, each having their own household, and she was an ideal wife to him. Perhaps he also loved her with some kind of platonic love – more like a sister than a wife, which follows from my historical research. Marie and Charles had spent a lot of time together in childhood as Isabeau of Bavaria had sent her least favorite son to Yolande of Aragon’s castles until she had recalled Charles back to Paris upon him becoming the Dauphin of France. In any case, there was some closeness and affection between them.

Why did so many of their offspring die? Marie d’Anjou’s parents were both descendants of King Jean II of France known as the Good (le Bon), so she had the Valois blood coursing through her veins on both paternal and maternal sides. Charles VII was a son of Charles VI of France, and he was extremely fortunate that neither he nor any of his surviving progeny suffered from his father’s mental illness, although Catherine de Valois, his sister, passed the genes of insanity on to her son – King Henry VI of England. Like his spouse, Charles was also descended from Jean II of France on his paternal side – he was Jean’s great-grandson. Isabeau of Bavaria brought some fresh blood to the family, but she herself was a product of generational inbreeding as the German House of Wittelsbach, to whom she belonged, was rather inbred. Charles and Marie were 2nd cousins, each of them carrying the inbred genes of the past generations, which must explain, at least partly, the weakness of their progeny and a high child mortality rate.

When Marie was already above 40, her husband fell in passionate love with Agnès Sorel, who served as a maid of honor to Isabella, Duchess de Lorraine (wife of Yolande’s son, Renée I of Naples). Beautiful, tall, and fashionable, Agnès was 19 years younger than Charles, and even if she disliked the situation at first, she could not have rejected her sovereign. Some novelists and historians believe that it was the aging Yolande of Aragon who asked Agnès to be close to Charles and inspire him to continue fighting against the English, but there is absolutely no proof of this theory. In fact, the breaks between battles during the last years of the Hundred Years’ War were explained by Charles’ cautious attitude to everything and by his substantial, progressive reforms in the realm, including the creation of the first standing, professional army in France with the goal to completely expel the invaders from the continent. I think that Agnès had attracted the attention of Charles who had never been in real love before meeting her, and then she became his mistress. It seems that there was deep affection between the lovers, and Queen Marie accepted it with grace and dignity even when King Charles created the position of official mistress for Agnès.

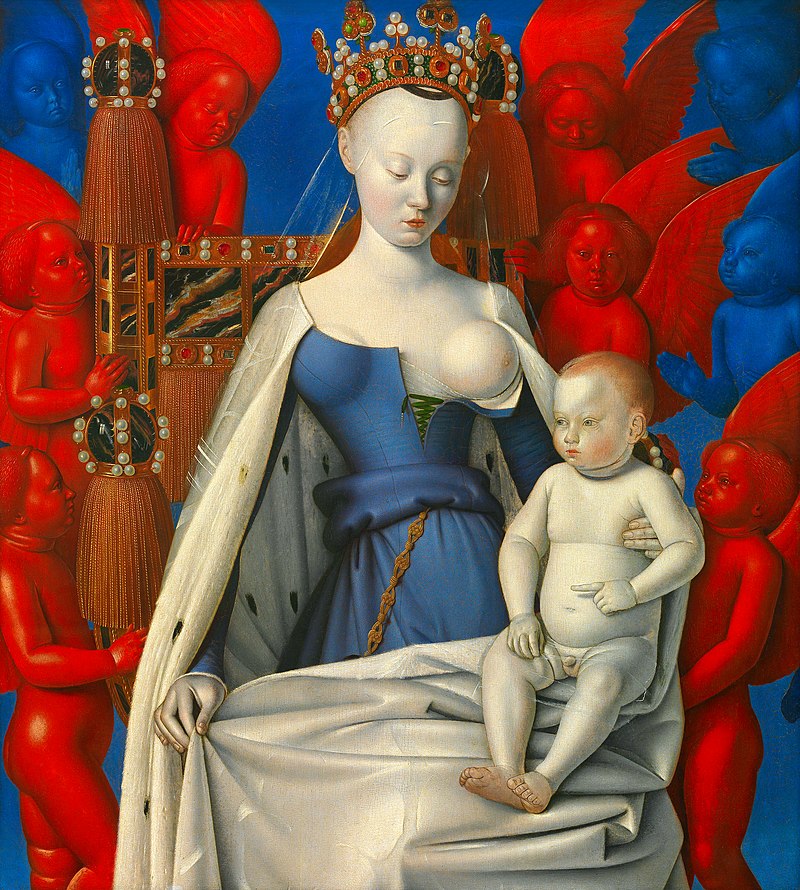

In history, Agnès Sorel, known by the sobriquet Dame de beauté (Lady of Beauty), became the first officially recognized royal mistress. Unlike Marie, Agnès was not shy, having extravagant tastes and loving luxury, and she made the fashion of low-cut gowns popular at court. Marie must have been horrified, feeling disdain towards Agnès, but she still behaved with dignity and paid respects to the keeper of her husband’s heart in the official environment. Perhaps Marie voiced her displeasure to Charles, but what could else she do? Agnès and Charles had 3 illegitimate daughters, and Marie endured his infidelities. Unlike Agnès, Marie did not become the subject of several contemporary paintings and works of art, but it probably did not interest her. Agnès had died in childbirth, or she was poisoned (her demise is still a mystery) after she had traveled from Chinon to join Charles on the campaign of 1450 in Jumièges. Afterwards, Charles was sad for some time, and Marie expressed her condolences for form’s sake. To distract himself from the loss of the love of his life and to assuage his heartbreak, Charles soon had Agnès’ cousin, Antoinette de Maignelais, installed as his official paramour, and Marie tolerated this affair and his few other mistresses whom he later bedded.

Due to the deaths of their many offspring, Marie began dressing dramatically in black, as if in sign of her perpetual mourning for them. It happened at some point between 1436 and 1441. Devoted to her surviving progeny and to her royal husband despite his escapades, she channeled her energy into raising the princes and princesses. The queen was known for her quiet demeanor, her kindness and piety, which was admired by nobles and the people of France. The tragedies caused Marie to retreat into religious life, and they could have widened the emotional rift between the spouses. The latter might explain the appearance of Agnès Sorel in Charles’ personal life and his other amorous conquests, which nonetheless continued simultaneously with the liberation of France from the English. The Battle of Castillon of 1453 in Gascony near the town of Castillon-sur-Dordogne, which ended with a decisive French victory, was considered the last battle of the Hundred Years’ War, and in spite of their disagreements, Marie and Charles must both have been happy to see their realm free of the invaders and to be able to rule without external threats.

Queen Marie remained in the shadows of her husband and later his mistresses, but she was not stupid at all. Yolande of Aragon had given her and her siblings a stellar education, and although she did not have a purely political mind, Marie presided over the Royal Council several times in the absence of her royal husband when Charles campaigned against the English. Her spouse trusted her enough to give her power of attorney as regent and the right to sign state documents in the position of his lieutenant. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Marie could have been the king’s councilor on certain occasions, most likely especially often during the period of the highest uncertainty and most grievous setbacks in his life – between 1422 and 1429.

For a long time, Marie was considered a timid queen without any ambition. I would call her a model queen who knew when she had to silently endure and who complied with all her duties – childbearing and the tasks assigned to her by Charles. Marie also liked extravagance to an extent that was necessary to stress her highest station in the realm – she was the Queen of France. The accounts of her household reveal that she played a managerial role at court and maintained it in an elegant, yet not excessive, splendor. In 1453-55, Marie paid more than 26,586 livres for redecorating and furnishing her apartments at the royal Château de Chinon. Her rooms were located on the first floor of the castle – on the same level as and, hence, rivalling those of Charles VII. The queen funded the decoration works of the rooms occupied by her ladies-in-waiting. There were also artists whom she patronized such as her official painter, Henri de Vulcop (a miniaturist painter and book illuminator). Marie had a musical chapel with 15 members, 2 of whom – her 2 chaplains, Pierre Basin and Jean Sohier, – served as composers of polyphonic music. In her late years, the Chinon gardens were redesigned at the queen’s behest.

Much to her chagrin, the relationship between King Charles VII and Queen Marie’s eldest son, Louis (the future Louis XII of France) was extremely strained. Due to his disagreements with his father and his growing impatience to rule as Charles’ successor, Louis endeavored hard to destabilize his father’s reign. The heir apparent openly despised his father’s mistress, Agnès Sorel, and after Agnès’ death, there were rumors that he had poisoned her. In 1446, Charles banished Dauphin Louis to his province, the Dauphiné, from where his disobedient son later fled to the court of Philippe the Good in Burgundy. In my opinion, the nastiest thing King Louis XI did was not to come to his father’s deathbed in 1461 when Charles VII beseeched his eldest son to return to France. Charles died without reconciling with Louis, and we don’t know what Marie thought of her son’s transgressions towards his father – I think she did not approve of Louis’ behavior.

After the death of Charles VII of France, who was already known as the Victorious (le Victorieux) on the 22nd of July 1461, Louis hurried to France and was crowned as King Louis XI. He met with Marie and granted her Château d’Amboise as her residence and the income from Brabant. Queen Marie mourned for her deceased husband and performed several pilgrimages in 1462-63, one of them to Santiago de Compostela to the shrine of the apostle Saint James the Great in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. This international pilgrimage resulted in gossip that Marie had acted as her son’s spy, but it is unlikely to have been true. Marie outlived Charles only by 2 years: she passed away at the age of 59 on the 29th of November 1463 at the Cistercian Abbaye de Chateliers-en-Poitou (now it is in Nouvelle-Aquitaine region) after her return from Spain. She is buried in the Basilica of Saint-Denis alongside her spouse, and Louis XI gave her lavish funeral despite his ascetic, frugal personality. Perhaps Louis loved his mother more than his father, but Marie’s death was not necessary for him to become the ruler of France, and affection is often colored in opaque and lethal colors where kingship was concerned.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville