Luca Marenzio (died on the 22nd of August 1599) was a far-famed Italian composer and singer of the late Renaissance, who was born on the 18th of October 1553 or 1554. He was one of the most prominent composers of madrigals. In total, Marenzio wrote around 500 madrigals. His works influenced the Renaissance music in the whole of Europe, including England where his the Musica Transalpina appeared in 1588 and initiated the madrigal boom in the country.

Like most musicians back then, Marenzio worked for Italian aristocrats: the Gonzaga, Este, and Medici families, but he spent most of his career in Rome. Starting from 1568, he served for 5 years to the Gonzaga family in the Duchy of Mantua. Then the musician went to Rome, where he was employed by Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo until the man’s death in 1578. Then Marenzio served Cardinal Luigi d’Este; while writing his first madrigal book, he was the cardinal’s maestro di cappella. Marenzio traveled with Luigi to Ferrara, the home of the Este family, where he took part in the opulent wedding festivities for Vincenzo Gonzaga and Margherita Farnese, for which he and several others composed music.

In Ferrara, Marenzio heard the newly formed Concerto delle donne, which consisted of the professional female singers with the repertory of ‘secret music’ that influenced the development of madrigals. While in Ferrara, Marenzio wrote and dedicated 2 books of madrigals to Duke Alfonso II and Lucrezia d’Este. During his employment with Cardinal Luigi, Marenzio became known as a talented composer and an expert lutenist. The cardinal passed away in 1586, and by this time, Marenzio was already internationally famous, with his numerous books of madrigals published and reprinted not only in Italy, but in France and in the Netherlands.

As he no longer had a patron, Luca Marenzio freelanced in Rome for some time, where he was able to earn quite a lot, according to his accounts. Then he moved to Verona, where he met Count Mario Bevilacqua and attended the Accademia Filarmonica – an association of musicians and humanists. By the end of 1587, Marenzio acquired a new patron: he served in Florence at the court of Ferdinando I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, where he stayed for 2 years. It seems that Marenzio was on bad terms with Giulio Caccini and some other Florentine composers, most likely due to the rivalry between them, and instead Marenzio befriended two Florentine dilettante composers – Piero Strozzi and Antonio de’ Bicci. In 1589, the artist came back to Rome, where he found new patrons, including Virginio Orsini who was a nephew of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. His another important patron was Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini, who was Pope Clement VIII’s nephew. This cardinal allowed Marenzio to have a comfortable apartment in the Vatican.

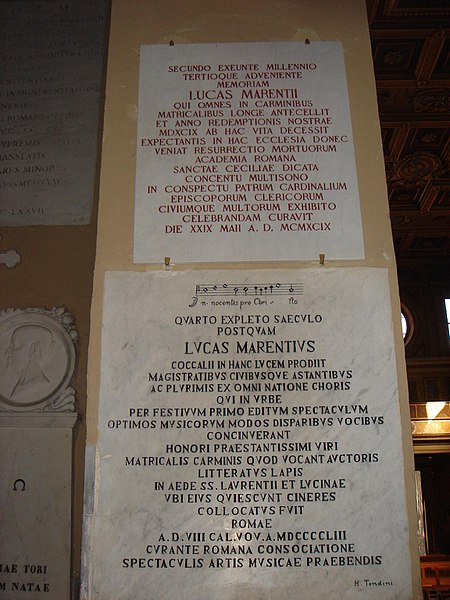

Marenzio’s final journey was the most incredible one in his career. At the Pope’s behest, he traveled to Poland between late 1595 and mid-1596, where he worked as maestro di cappella at the court of King Sigismund III Vasa in Warsaw. While in Poland, Marenzio wrote and directed sacred music, including motets for double choir, a Te Deum for 13 voices, and a Mass, the music for which was lost. Unfortunately, this voyage ruined the artist’s health, and the composer returned to Italy and headed to Mantua again, where he wrote another book of madrigals dedicated to the House of Gonzaga. The artist then relocated to Rome, where soon he died at the garden of the Villa Medici on Monte Pincio. Marenzio was given lavish funeral, sponsored by Ferdinando de’ Medici and the Pope, in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina.

Marenzio wrote sacred music such as masses, motets, and madrigali spirituali (madrigals based on religious texts), but his main musical output was madrigals. They vary significantly in style, technique, and tone through the several decades of his career. To Marenzio, each madrigal text was individual, and at each of his works he looked from different angles, as if each of them was a new problem to be solved. In his lifetime, the composer published 23 books of madrigals and related forms, including 1 book of madrigali spirituali. The style of his compositions showed an increasing seriousness of composition and tone throughout his life, but Marenzio could always create uplifting things within one serious madrigal. In his last years, he not only wrote serious and somber music, but also experimented with chromaticism. By the end of his captivating and prolific life, the artist was immensely skilled in evoking all kinds of moods and creating all kinds of images suggested by his poetic madrigals, which attested to his tremendous talent.

One of the finest examples of the composer’s madrigals is ‘Due rose fresche,’ or in English ‘Two roses.’ This is a beautifully crafted setting of a sonnet by Petrarch, describing an evidently imaginary encounter between the poet, his beloved, and a somewhat enigmatic wise old man.

Two brilliant roses, fresh from Paradise,

Which there, on May-day morn, in beauty sprung

Fair gift, and by a lover old and wise

Equally offer’d to two lovers young:

At speech so tender and such winning guise,

As transports from a savage might have wrung,

A living lustre lit their mutual eyes,

And instant on their cheeks a soft blush hung.

The sun ne’er look’d upon a lovelier pair,

With a sweet smile and gentle sigh he said,

Pressing the hands of both and turn’d away.

Of words and roses each alike had share.

E’en now my worn heart thrill with joy and dread,

O happy eloquence! O blessed day!

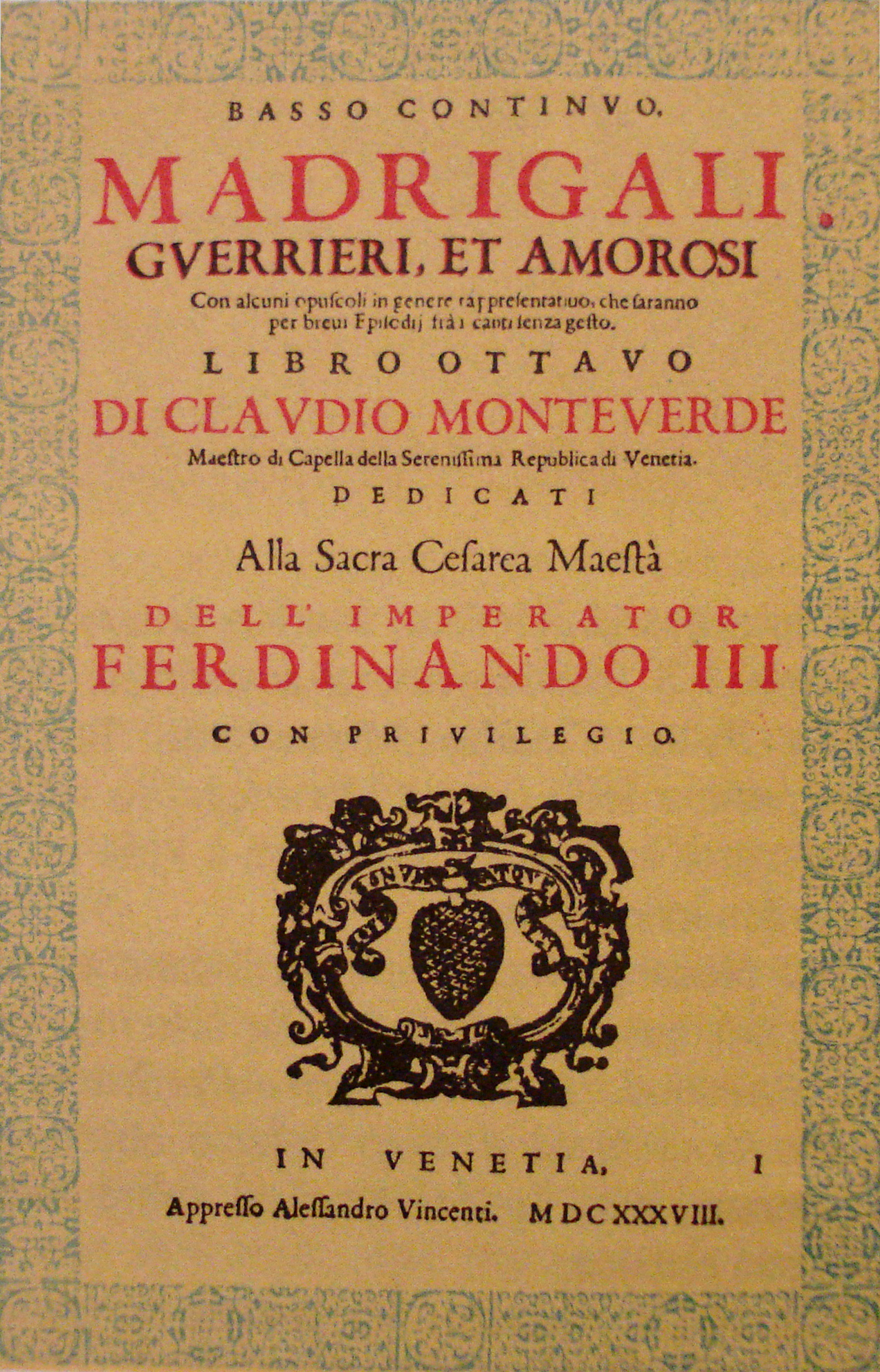

After his death, Marenzio’s style and works highly influenced many composers and singers of the late Renaissance and the early Baroque eras. Luca Marenzio remained known for at least 2 centuries after his death, admired for the poetic sensibility, poise, grace, and purity of his output, and of course for his tremendous, emotional madrigals. In 1607, he was recognized by Giulio Cesare Monteverdi, who was the younger brother of Claudio Monteverdi, as a composer of the seconda prattica, alongside such names as Wert, Peri, and Caccini. For the most part intended for connoisseurs, the madrigals, especially numerous illustrious works of the 1590s, remain music for the refined ear that is capable of understanding and appreciating them. Yet, those people who are not experts in music, but who want to open something new, can enter and almost drown in this rarefied world of madrigals, enjoying the intense human passions and poetic expressions in them.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville