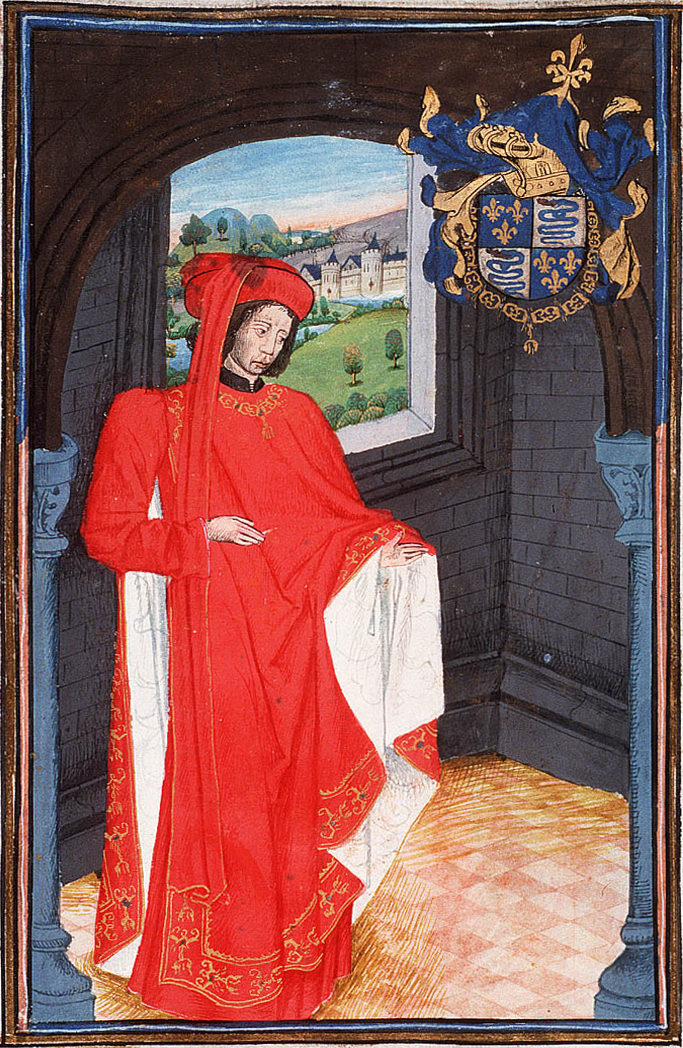

Charles d’Orléans was born in Paris at Hôtel Saint-Pol on the 24th of November 1394. It was a bad irony that he first saw the world on the next day after his father’s barbaric assassination in the dark street of Paris upon the orders of Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, but of course in a different year. Charles was the oldest surviving son of 2 first cousins – Louis, Duke d’Orléans and the holder of many other titles, and his wife, Valentina Visconti. After his father’s tragic murder on the 23rd of November 1407, Charles succeeded him as Duke d’Orléans, Duke de Touraine, Count de Valois and de Blois, Count d’Angoulême, de Périgord and Soissons. Charles also became Lord of Coucy and the nominal Lord of Asti in Italy via his mother, Valentina.

Valentina became a shell of her former self and succumbed to indescribable melancholia. In a year after his father’s murder, she became seriously ill, and her children had to endure the pain of her death in December 1408. On her deathbed, Valentina’s 3 surviving sons – Charles, Duke d’Orléans, Philippe, Count of Vertus, and Jean, Count d’Angoulême – swore the oath of vengeance on Jean the Fearless, who was not punished by King Charles VI of France known as the Mad (le Fou). They were expected to represent the Armagnac faction in France, with Charles being the leader of his late father’s partisans. The monarch and, accurately speaking, his regent and wife – Queen Isabeau – forced the Duke of Burgundy and Charles d’Orléans to pledge a reconciliation.

A year before Louis’ murder, at the age of 12, Charles had married his first cousin, Isabella de Valois, who was a daughter of Charles VII and widow of Richard II of England. The bride was 5 years older than her husband, so they consummated their marriage in 1408, and then Isabella fell pregnant. In 1409, Isabella passed away in childbirth, and their daughter, Jeanne, would marry Jean II d’Alençon in 1424. In 1410, after a short period of mourning, Charles d’Orléans married Bonne d’Armagnac, daughter of Bernard VII, Count d’Armagnac. It was when Charles, influenced by his father-in-law, began to work against the Burgundians, and those who joined his cause and Bernard were called the Armagnacs. He and Bonne were on good terms, but they had no childless.

Agincourt… This might send shivers down the spine of the French. The Battle of Agincourt of 1415 became a bloodbath for French knights and the trap for many French nobles. After having been discovered trapped under a pile of corpses, Charles d’Orléans was taken to England as a precious prisoner of Henry V of England, for he was a Valois prince of the blood. During the next 24 years, Charles and many others, including his brother Jean d’Angoulême, would spend being moved from castle to castle, including the Tower of London and Pontefract Castle. To the credit of the English, the royal prisoners lived in luxury, having been allowed to walk in the gardens and hunt. But no one considered the possibility of their release both before and after Henry V’s death in 1422. Even without their captor, the Hundred Years’ War continued, where their cousin, Charles VII of France, contested his claim for the French throne with the English.

Charles always had a passion for books and reading, and he also wrote some poems before his incarceration. However, it was during his imprisonment in England that he discovered his great talent for poetry and wrote hundreds of poems, many of them melancholic. Now he is remembered as one of the most accomplished medial poets. There are several books of poetry that were written in the “ballade and rondeau” fixed forms. An example of one of his mournful poems is ‘En la forêt de longue attente,’ which is a lament on his lack of liberty. Some poems were also dedicated to his heartache caused by his incarceration, and in this poem Charles begged someone, perhaps the Lord, to strengthen his heart and him in order to withstand his many misfortunes.

His most famous poem in the French language is ‘Le Printemps’ (Spring Time) by Michael R. Burch:

Jeunes amoureux nouveaulx

En la nouvelle saison,

Par les rues, sans raison,

Chevauchent, faisans les saulx.

Et font saillir des carreaulx

Le feu, comme de cherbon,

Jeunes amoureux nouveaulx.

Je ne sçay se leurs travaulx

Ilz emploient bien ou non,

Mais piqués de l’esperon

Sont autant que leurs chevaulx

Jeunes amoureux nouveaulx.

Let’s translate this marvelous poem into English:

Young lovers,

greeting the spring

fling themselves downhill,

making cobblestones ring

with their wild leaps and arcs,

like ecstatic sparks

struck from coal.

What is their brazen goal?

They grab at whatever passes,

so we can only hazard guesses.

But they rear like prancing steeds

raked by brilliant spurs of need,

Young lovers.

Perhaps the captive Duke d’Orléans was lamenting his youth that was lost because of the battle of Agincourt and its severe consequences for him. Most likely, he was not allowed to have mistresses while in captivity, for the English would not have allowed French “pretenders” to sire any children, aiming to make the Valois lines go extinct. Charles’ wife, Bonne d’Armagnac, died in 1430, or 10 years before her husband’s release from captivity. Charles’ daughter, Jeanne, died in 1432 and had no issue, but most likely, Charles received sad news about their demises from France. He must have rejoiced upon learning about the end of the Burgundian-Armagnac War with the signing of the Treaty of Arras of 1435 between Charles VII of France and Philippe the Good, Duke of Burgundy. It was a light at the end of the tunnel for the Duke d’Orléans.

Indeed, Charles was released in 1440 by joint efforts of Charles VII and those of his former enemies – Philippe the Good and his wife, Isabella of Portugal. When he set foot on French soil again, Charles was 45, and he spoke English better than French or at least as well as his own native language. The duke married his 3rd wife – Maria of Cleves, who was 32 years him junior – in Burgundy, and part of her dowry was used to pay his ransom. Philippe the Good created for Charles a Knight of the Golden Fleece. Soon Charles and his young wife returned to Orléans, much to the population’s joy, and splendid celebrations followed. Maria and Charles did not have any children for 17 years, and when Charles turned 63, Maria birthed their daughter – Maria d’Orléans. They became parents to Louis d’Orléans (future Louis XII of France) and Anne d’Orléans (she would become the Abbess of Fontevrault and Poitiers). Despite their age significant difference, Maria and Charles had a good marriage because they had a lot in common: like her husband, Maria was a patron of letters and an active poet. Both Charles and Maria were patrons of the arts in Orléans.

The overwhelming majority of Charles’ writing includes ballads and rondels. He mainly wrote ballads before his release and later channeled his energy into creating rondels. As he got more experience in poetry, Charles moved away from a malleable form that he exploited to the fullest towards a more complex and even more malleable form. There is no clear pattern in his ballads, but there is a predilection for the rondel with a 4-4-5 or 4-3-5 strophic arrangement. His mature verses displayed fewer emotions, and most of his verses were not amorous. On the contrary, they were amusing, sarcastic, ironic, and wistful towards life and its lost pleasures. Many of his works reflected that Charles understood the vanity of titles and aristocracy, for he had gained wisdom. His poetry is notable for its masterful use of allegory. During his imprisonment, Hope, Sadness, and Loyalty recurred in his verse; in his later poems Melancholy and Care prevailed.

Charles, Duke d’Orléans, died in Amboise on the 5th of January 1465 at the age of 70. Most likely, the reason for his death was old age. Charles was buried at Saint Denis Basilica with pomp. His wife later remarried one of her gentlemen of the chamber and passed away at the age of 60 in Chaunay. After the extinction of the senior Valois male line in 1498, the Orléans line would come to power with the ascension of King Louis XII of France, former Duke d’Orléans.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville

You are welcome to use my translation of “Le Printemps” by Charles d’Orleans, but please credit me as the translator. — Michael R. Burch

Hello! I do not think I saw that you had translated this poem because you normally search translation online, and you cannot always find the translator’s name. These days you can often see English and French versions of some poem (or it can be given in some other language) and nothing else save the author of the original poem. I will add you.