Valentina Visconti was born in Milan in 1370 or 71 to Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the 1st Duke of Milan, and his first spouse, Isabelle de Valois. Isabelle was a daughter of King Jean II the Good (le Bon) and his first wife, Bonne de Luxembourg. The girl’s name was unusual for the period, and she appears to have been named after her paternal great-grandmother – Valentina Doria, wife of Stefano Visconti. Valentina had 3 brothers: Gian Galeazzo, Azzone, and Carlo, but they all died either in infanthood or in early adulthood. Isabella passed away in childbirth with Carlo in 1372.

Her paternal grandmother, Bianca of Savoy, raised an orphaned Valentina. Bianca was a cultured woman, one who loved the arts and considered it necessary for girls to be educated not only in traditional tasks, but also in literature, the arts, and other subjects of enlightenment. The popularity of heraldic songs within the Visconti family is largely attributable to the influence of Bianca and her spouse, the late Galeazzo II Visconti. Bianca passed on her love for heraldic songs to her granddaughter. The following composers worked in northern Italy between 1350 and 1400: Giovanni da Cascia, Jacopo da Bologna, Donato da Cascia, Antonello da Caserta, Bartolino da Padova, and Johannes Ciconia, and some of them were patronized by the Visconti family.

The proposal of Valentina’s betrothal to Louis de Valois, Duke d’Orléans, was first made in 1385. It could have originated at the Angevin Valois court, and the knight Pierre de Craol traveled between Milan and Paris for some time. Yet, soon the negotiations were stalled, and Duke Gian of Milan endeavored to have his daughter married off to the half-brother of King Wenceslaus of Germany and Bohemia – John of Görlitz, a member of the House of Luxembourg and Duke of Görlitz. At the same time, Gian also considered the possibility of marrying Valentina off to Louis II of Anjou, titular King of Naples from the Valois House of Anjou, but his mother, the formidable Marie de Blois, Dowager Duchess d’Anjou, did not want this marriage to proceed.

When King Wenceslaus learned about Gian’s double negotiations, he sent to the Duke of Milan an angry letter full of disparagements, cancelling all further negotiations. Therefore, Gian remained with only one alternative: to have Valentina betrothed to her maternal first cousin – Louis d’Orléans. Due to the couple’s close blood relationship, Gian obtained a papal dispensation for the marriage in the autumn of 1386. It is likely that Bianca of Savoy orchestrated this marriage due to the close connections between the House of Savoy and the royal House of Valois.

The marriage contract was signed in January 1387 in Paris. Young Louis and Valentina were married by proxy on the 8th of April, 1388. Valentina’s dowry was magnificent: it included the County of Vertus, which had been the dowry of her mother for her marriage to Gian, and the city of Asti, and the huge sums of 450,000 florins in cash and 75,000 florins in jewelry. Valentina’s fiancé was a younger brother of King Charles VI of France, so it was expected of her to bring a substantial dowry for this excellent match. Her father, Gian, consented that his daughter and her descendants would have the right to take the ducal throne of Milan in absence of male heirs, and this was fixed in the marriage agreement. Later, this would become the very reason for the Italian wars when King Louis XII of France and his successor, King François I of France, would wage wars against the Houses of Sforza and of Habsburg for the ducal throne of Milan.

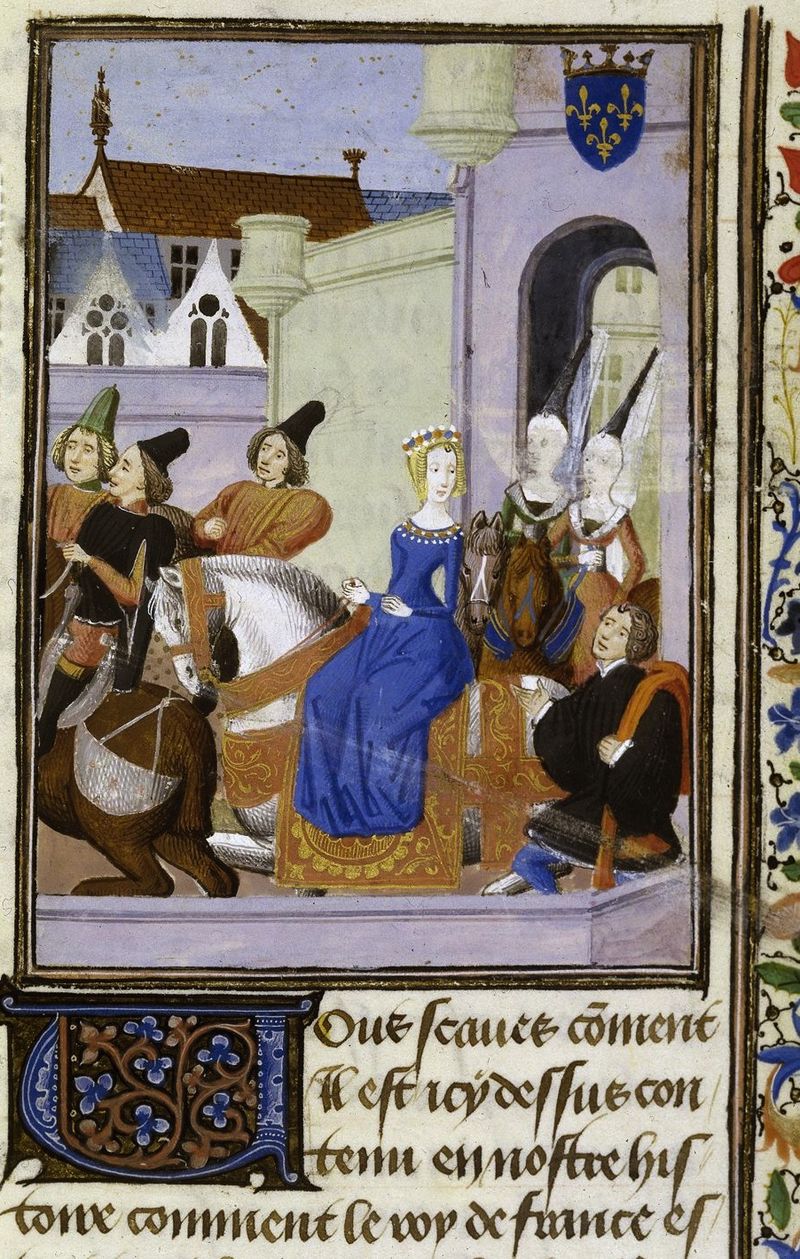

Bianca of Savoy died in 1387, which was a family tragedy for all the Visconti. Gian Galeazzo remarried in October 1380, selecting his first cousin, Caterina Visconti, as his second bride. With her, Gian had 2 sons: Gian Maria and Filippo Maria. Gian Maria would die childless, while Filippo Maria would have only illegitimate daughter – Bianca Maria Visconti, who would later marry Francesco I Sforza. The duke was a devoted father to his daughter, and he was also worried about the succession in the Visconti dominions. So, Valentina’s departure to France was a bit delayed until the duke’s son, Gian Maria, was born in September 1388. Finally, Valentina said adieu to her loving father and departed for France with her grand trousseau and procession.

Her paternal cousin – Amadeus VII, Count de Savoy, escorted Valentina to her new country. A retinue of 400 knights accompanied them. The marriage between Valentina and Louis d’Orléans was formally solemnized in the city of Melun on the 17th of August 1389. The bridegroom was pleased with his wife: Valentina was a young, tall, slender, and attractive brunette, one who was almost his coeval – she seems to have been only 1 year older than him. The years between 1489 and 1494 were relatively happy for the couple: they lived a vivacious and sumptuous life in Paris, often whirling in a series of merry pageants at the royal court. Louis and Valentina were in high favor with King Charles VI, although the monarch’s wife, Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, detested the Duchess d’Orléans. Isabeau was a granddaughter of Bernabò Visconti, who was deposed by his nephew, Gian Galeazzo Visconti in 1385. Isabeau would never warm up to Valentina.

Valentina and Louis resided at Hôtel de Saint-Pol, at Château de Vincennes, and at other royal residences. Out of their first 4 children, only one son – Charles, Duke d’Orléans (later a well-known medieval poet) – survived into adulthood. Their happiness came to an abrupt end: the monarch began to exhibit peculiarly odd behavior around 1392-93. During the royal army’s slow progress to Brittany, Charles was swinging his sword at his guards while they were near Le Mans, in a forest. Charles killed several men and then fell into a coma, and since then he suffered from increasingly longer periods of insanity. The ruler’s secretary, Pierre Salmon, spent much time in discussions with the king to cure him with the help of benevolent dialogue. While the psychotic Charles did not want to see Isabeau anywhere near him and at times was aggressive towards her, Valentina’s presence calmed him down. Not recognizing his many relatives and courtiers, Charles always recognized Valentina and became angry if she did not visit him for some time.

Valentina was invited to the king on multiple occasions to calm him, and as a compassionate woman, she felt that it was her duty to help her sovereign and cousin. Back then, nothing was known about the special treatment of people suffering from mental disorders and schizophrenia. As the royal doctors failed to cure the monarch, the nasty gossip was spreading that Valentina must be a witch, which was probably started or at least supported by Isabeau of Bavaria. Valentina’s father, Duke Gian, was so outraged at the tidbits of his daughter’s sorcery that he threatened to declare war on France. Other horrible rumors were that Valentina tried to poison the Dauphin of France, and even that her father had told her before Valentina’s departure to France:

“I will not see you again until you are Queen of France.”

I think that the Duke of Milan never said that. Valentina was a good and God-fearing woman, and she would never have perpetrated regicide. To me, this web of lies around the noble-minded Valentina might have been woven by the cunning Isabeau. Philippe the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, was not Valentina’s supporter either because Philippe had a political feud with Louis d’Orléans over the power in France due to Charles’ inability to rule. Philippe could have encouraged these rumors about Valentina to harm the reputation of the Orléans family. Isabeau and Philippe might have plotted against Valentina together to diminish her influence over the king. Representing competing branches of the Visconti family at the Valois court, the women promoted their families’ causes, and the descent of Valentina’s star gave Isabeau the chance to move against her rival. An agitated Louis removed his spouse to Château d’Asnières outside Paris for her safety.

Valentina was not the only one to be accused of witchcraft. Louis’ own uncle, Philippe the Bold, accused Louis d’Orléans of using black magic to cause the psychosis of King Charles VII. Philippe’s campaign against his own nephew started in 1392 with the goal to accumulate more power at the expense of Louis’ control over the monarch. Truth be told, Philippe seems to have genuinely believed that someone had bewitched his ruling nephew, but his actions against his another nephew, Louis, were explained by political motives. Thus, both Louis and Valentina were companions in misfortune – they were blamed for something they did not commit.

In later years, Valentina lived at Château de Blois and in Louis’ other palaces in the province, but he regularly visited his wife and their children. Marie d’Harcourt, Louis’ cousin, lived with Valentina as her primary “demoiselle.” Louis d’Orléans is frequently painted as a licentious lover of luxury and a tyrannical spendrift, one who had countless mistresses and oppressed the people of France by raising taxes as he governed for his insane brother. Louis was as power-hungry and ambitious as other nobles, especially royal men of the time, but he was not ruthless, unlike Jean the Fearless, the successor of Philippe the Bold. Louis could have had paramours, but his only acknowledged illegitimate son with Mariette d’Enghien – Jean de Dunois – was born in 1402. So, Louis was either careful not to impregnate his mistresses if we choose to believe that he led such a promiscuous life, or he did not acknowledge them. Both versions are possible.

Louis and Valentina had a happy marriage. He was pleased with his spouse and respected her for her graceful and benevolent character, as well as for her intelligence and for the admiration for the arts. The spouses had a great deal in common: they loved luxury and collected objects d’art, and Louis was a very wealthy man. The spouses both collected books and manuscripts throughout their lives, which would later be added to their descendants’ vast book collections. Valentina had arrived in France with 12 rare Italian books in her trousseau. Valentina was also an accomplished harpist. Valentina was a patroness of the medieval French poet Eustache Deschamps (also known as Morel), who wrote poetry in her honor. Christine de Pizan, the first professional female writer, referred to Valentina Visconti in her works as an example of contemporary French female leaders, although by 1405 Valentina was villainized and exiled from the French court.

In her most famous literary work, ‘Le Livre de la Cité des Dames’ (The Book of the City of Ladies), which was finished by 1405, Christine de Pizan wrote:

“Que dire de la fille de feu le duc de Milan, Valentine, duchesse d’Orléans, épouse de Louis, fils du roi de France Charles le Sage? Pourrait-on trouver femme plus prudente?”

In English it means:

“What could I say about Valentina Visconti, Duchess of Orléans, wife of Duke Louis, son of Charles, the wise King of France, and daughter of the Duke of Milan? What more could be said about such a prudent lady?”

Valentina and Louis had 8 children together, but only 3 of their 6 sons and one of their daughters survived into adulthood. They buried many offspring because of the high child mortality rate back then, and because of their close blood relationship. The poet Charles, Duke d’Orléans, was a direct ancestor of King Louis XII of France; Jean, Count d’Angoulême, was a grandfather of King François I of France. Both Charles and Jean were destined to spend many, many years in English captivity and return to their home country already middle-aged men. Valentina’s daughter, Marguerite, was an ancestress of Duke François of Brittany and, hence, of Anne of Brittany, wife of both Charles VIII and later of Louis XII. How closely they were all related!

At the end of November 1407, Valentina received tragic news – her husband had been butchered in the streets of Paris on the orders of his cousin – Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. A shocked Valentina must have not been amazed because Louis and Jean were in constant conflict over the governance of the kingdom, and she knew that her deceased husband would never have resorted to violence. To her surprise, Queen Isabeau summoned Valentina to Paris for the first time in years, and she rushed to the capital. We can imagine what Valentina felt: Louis was rumored to have been a lover of the prurient Isabeau and even the father of her several children, perhaps even the father of the future Charles VII. For some time, Isabeau and Louis had been allies against the Burgundian faction, so the Duke d’Orléans had indeed spent much time with the queen, and in the absence of his wife, Louis could have succumbed to temptation. It is amusing that some historians claim that Isabeau later became a lover of Jean the Fearless.

Regardless of her feelings, Valentina dressed dramatically in black and went to Charles VII. She took her two sons, Charles and Jean, to Paris. Holding the hands of her offspring, the duchess pleaded with the monarch for justice according to Isabeau’s advice. Perhaps Isabeau at first wanted to punish the murderer of her lover, if Louis had sexual relations with her, which we do not know for a certainty. During their meeting, King Charles was in one of the rare moments of lucidity: he was grief-stricken with his brother’s tragedy, and, after lifting Valentina from her knees, he kissed her hands and promised that his brother’s murder would be avenged. Indeed, Jean the Fearless would have been prosecuted as a vassal of the King of France if Charles did not succumb to the demons of darkness again, and if Jean the Fearless would not have become so powerful. The Duke of Burgundy even had the theologian Jean Petit from the University of Paris to preach about the necessity of “tyrannicide” because Louis d’Orléans was himself “a tyrant.”

Valentina and her boys returned to Blois, but in August 1408, she arrived in Paris. She visited King Charles whose mind was not clear and whose responses shocked her. Queen Isabeau was allied with Jean the Fearless, for she wanted to keep herself in power while the Burgundian faction was winning. The gossip of Isabeau’s liaison with Jean of Burgundy began circulating, according to some sources. Enraged by the lack of justice towards her husband whom she seems to have loved, a disconsolate Valentina journeyed back to Blois. At her behest, the walls in her quarters in the château were covered in black fabric, where she spent hours praying for Louis’ soul.

On the fabric, in which the walls were swathed in, Valentina’s new motto was written:

“Rien ne m’est plus, plus ne m’est rien.”

In English it means something very despondent:

“Nothing remains to me, nothing more to me.”

On the 4th of December 1408, Valentina passed away of typhoid at the age of 38, although many said that she died of a broken heart. Her offspring surrounded her and vowed to avenge their father’s demise. Louis’ murder resulted in the Burgundian-Armagnac war in France until it ended with the reconciliation between the Armagnacs and the Burgundian faction with the signing of the Treaty of Arras of 1435. Valentina’s sons did not participate actively in this war because of their English captivity; King Charles VII of France would later become the center for the Armagnacs’ cause to liberate France from the English. As for Milan, Valentina’s legacy was a bit tarnished because of the Milanese people’s sufferings when her male descendants – Louis XII and François I – would claim the duchy as their own, but in the end unsuccessfully. Anyway, Valentina’s statue is among those of the many queens that adorn the Palais de Luxembourg gardens in Paris.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville

I wait your novel about Valentina Visconti with impatience.

Hello! Thank you for your interest in this novel. The novel about Valentina Visconti and Louis d’Orléans is a challenge, for you cannot use English and Burgundian sources because you will not see the real Louis and Valentina, especially Louis who was rather maligned by the Burgundians. So, I am using only French chronicles and Italian ones about Valentina.