Baldassare Castiglione, Count of Casatico, was born on the 6th of December 1478. He was an Italian courtier, diplomat, soldier, and, most importantly, an illustrious Renaissance author. Born in Casatico, near Mantua, into a family of the minor Italian nobility, he was related through his mother, Luigia Gonzaga, to the ruling dynasty of Mantua – the House of Gonzaga. He spent much time in Milan, Urbino, Mantua, and many other places, including England and Spain.

Castiglione studied humanism and classics for 5 years between 1494 and 1499 in the city of Milan, which was ruled by Duke Ludovico Sforza at the time. The young man was enrolled at the school of the famous teacher of Greek and editor of Homer Demetrios Chalkokondyles, known as Demetrius Calcondila. After his father had passed away in 1499, Castiglione returned to Mantua and served Francesco II Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua, for whom he went on diplomatic missions in Italy. Castiglione accompanied the Marquess of Mantua in 1499 in King Louis XII of France’s triumphal entrée into Milan, for the Duchy of Mantua was allied with France at the time. On one of his trips, Castiglione made acquaintance with Francesco’s brother-in-law – Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, who was married to Francesco’s sister, Elisabetta Gonzaga.

In 1504, the Marquess of Mantua reluctantly released Castiglione from his offices and allowed him to enter into the service of his brother-in-law. Castiglione moved to Urbino and began working for the Duke of Urbino, whose court was one of the most refined in Italy. The court’s magnificence was attributable to its skillful management by Duchess Elisabetta and her sister-in-law, Emilia Pia. The talented hand of Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, commonly known as Raphael (he was a native of Urbino) painted these two women, as well as many other Italian aristocrats. Notable people of the time frequented Urbino, among them Pietro Bembo (an Italian scholar, poet, and literary theorist), Giuliano de’ Medici (the 3rd son of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Magnificent), Cardinal Bibbiena (an Italian cardinal and comedy writer), Francesco Maria della Rovere (a nephew and adopted heir of the ducal couple).

The Duke and Duchess of Urbino organized regular intellectual debates in their circles of intellectuals. Lavish pageants and festivities at their court were majestic, and the concept of courtly love and medieval chivalry were at the core of the cultivated values. Despite all this merriment, Elisabetta and Guidobaldo had their own sorrows: they were childless, and despite all their efforts to have an heir, it did not happen due to the duke’s health issues. Elisabetta took the best care of her husband, which impressed everyone. Guidobaldo and Elisabetta fled Urbino in 1502 from Cesare Borgia, but they returned after the death of Borgia’s father, Pope Alexander VI.

Baldassare Castiglione felt a sort of platonic affection for Duchess Elisabetta. Her bright star of intelligence and the example of her humility and devotion to her ailing husband inspired him to write about her and in her honor. Elisabetta became a muse for Castiglione, one who shines through Castiglione’s literary output: in his Latin poems and in his poems in vulgar tongue, as the Italian language was called back then, in his eclogue ‘Tirsi’, and in his pages commemorating Duke Guidubaldo, who breathed his last in 1508. Elisabetta also influenced the way Castiglione wrote or touched upon the most intimate themes in his writings in all the genres and in the forms. Their close relationship developed in Castiglione a new understanding of the ideal woman. Elisabetta was a unique woman of her era: a paragon of intelligence, virtue, valor, and devotion, the finest second half of the ailing, yet refined Guidubaldo, despite their personal and political misfortunes.

Castiglione’s most interesting connection at the court of Urbino was with Raphael, for whom the duke commissioned the painting ‘St. George and the Dragon’ as a present for King Henry VII of England. In this painting, the saint wears the blue garter of the English Order of the Garter, for Raphael’s patron – Duke Guidobaldo of Urbino – had been rewarded this honor by Henry VII. Castiglione traveled to England and carried the gift for the Tudor ruler, where he also accepted the honor in his master’s stead. Nevertheless, Leopold Ettlinger, a German 20th-century historian of the Italian Renaissance, claimed that ‘St. George and the Dragon’ could not have been created by Raphael for this occasion. But when how did the masterpiece end up in England when we know that by 1627 the painting belonged to William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke?

Ettlinger wrote of this situation in this historical works:

“The story-that [the St. George] was painted as a gift for the King of England is a modern legend unsupported by any historical evidence.”

In 1506, already after his return from England, Castiglione composed and acted in a pastoral play – his eclogue (a poem in a classical style on a pastoral subject) called ‘Tirsi.’ In this work, he recreated the court of Urbino allegorically and dramatically through the figures of 3 shepherds; the work where the ancient classics (Virgil and Homer) are combined with contemporary poetry, with beliefs of humanists such as Angelo Ambrogini known as Poliziano. Castiglione described the court and his life in Urbino in his diplomatic letters, which were written in a literary form.

Duke Guidobaldo’s death brought a great deal of sorrow to Castiglione. Francesco Maria della Rovere succeeded as Duke of Urbino and offered Castiglione to continue serving for him. Francesco was commander-in-chief of the Papal States and armies, and during Pope Julius II’s conflict against Venice, Francesco and Castiglione participated in the Italian wars. In reward, Castiglione received the title of Count of Novilara, which was a fortified town near Pesaro.

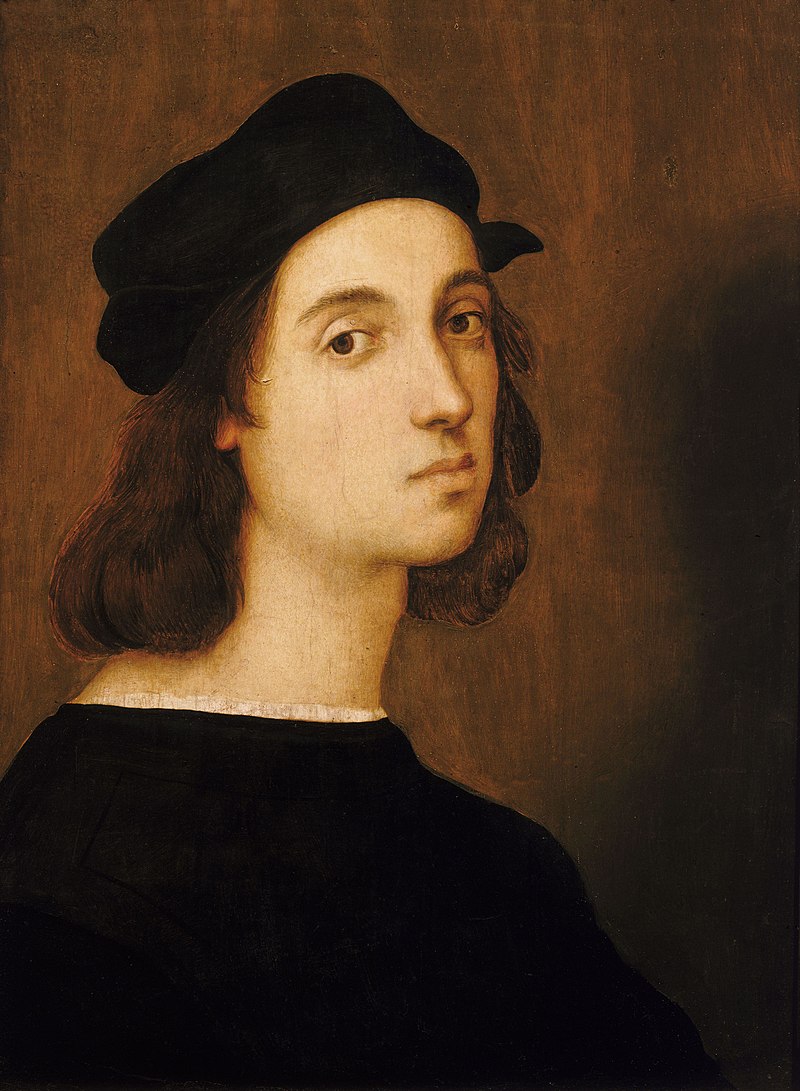

Castiglione had a close relationship with Raphael. They both had the same ideas regarding beauty and harmony, the same Renaissance values. Their mutual affinity finds its clear expression in Raphael’s stunning, yet simple portrait of his friend, which was completed during the winter of 1514-15 when Castiglione, appointed by the Duke of Urbino to be an ambassador at the court of Pope Leo X, was in Rome. The artist had been working there since 1508. Raphael depicted Castiglione in an elegant, yet modest, attire, which was trimmed on the front and upper sleeves in gray squirrel fur laced, and which fitted the concept of the accomplished gentleman. Castiglione’s hair is wrapped in a turban over, which sits a beret with a notched edge adorned with a medallion. The immediacy, freedom of expression, and expressive vivacity are all obvious in this work.

When Raphael died in 1520, Castiglione was grief-stricken. He composed a sonnet in the memory of his friend and man who also inspired many of his writings. In Italian it is:

Sonnet on the death of Raphael

Quod lacerum corpus medica sanaverit arte,

Hippolytum Stygiis et revocarit aquis,

Ad Stygias ipse est raptus Epidaurius undas;

Sic precium vitae mors fuit artifici.

Tu quoque dum toto laniatam corpore Romam

Componis miro, Raphael, ingenio,

Atque urbis lacerum ferro, igni, annisque cadaver

Ad vitam, antiquum jam revocasque decus,

Movisti Superum invidiam, indignataque mors est

Te dudum extinctis reddere posse animam,

Et quod longa dies paulatim aboleverat, hoc te

Mortali spreta lege parare iterum.

Sic, miser, heu, prima cadis intercepte juventa,

Deberi et morti nostraque nosque mones.

The sonnet on the death of Raphael is translated into English in the following way:

Because he healed the broken body with his medical art,

And recalled Hippolytus from the waters of the Styx,

The Epidaurian himself was dragged to the Stygian waves;

Thus the price of life was death of its master.

You too, Raphael, having restored the mangled body

Of Rome with your miraculous skill,

And having recalled to life and ancient glory

The body of our city maimed by sword, fire, and years,

Have moved the Gods to jealousy, and death is indignant

That you have returned to life what had long been extinct,

And that you once again renewed, thereby disdaining the law of death,

what a long period had slowly taken away.

Thus, alas, unfortunate one, you lie taken away in the flowering of youth,

And warn us that we owe all that we have to death.

In 1516, Castiglione returned to Mantua and married the young Ippolita Torelli, who was a daughter of condottiere Guido Torelli of Montechiarugolo (near Parma). The marriage lasted for 4 years, and they had 3 children, including their son – Camillo Castiglione. To Castiglione’s profound grief, then Ippolita died of some illness. Castiglione loved his wife, and this feeling was not like the idealized platonic love for Elisabetta – it was more earthly and more sensual. Then Castiglione again moved to Rome to serve as an ambassador, but this time for the ruler of Mantua. In 1521, Castiglione began his ecclesiastical career; perhaps this decision was influenced by his bereavement. In later years, Castiglione journeyed to Spain as ambassador of the Holy See and lived at the court of Emperor Charles V. As a result, when the Sack of Rome of 1527 happened, Pope Clement VII suspected that Castiglione could knew about the emperor’s intentions to capture the city and establish the Habsburg dominance in the whole of Italy.

Castiglione later received the Pope’s apologies. Charles V gave him the position of Bishop of Avila, and Castiglione moved to Spain. Castiglione died of the plague in Toledo on the 2nd of February 1529 and was at first interred in the chapel of San Idelfonso. At the behest of his mother, his remains were later transferred to Mantua: Castiglione was buried in the sanctuary of S. Maria delle Grazie, just outside of the city. The Pope took Castiglione’s 3 young children into his protection, donating a large sum for their education. The artist’s tomb was constructed by the Mannerist painter and architect Giulio Romano (a pupil of Raphael). Romano’s sculpture of the resurrected Christ graces Castiglione’s tomb. There is a famous inscription on a monument to Castiglione:

“Baldassare Castiglione of Mantua, endowed by nature with every gift and the knowledge of many disciplines, learned in Greek and Latin literature, and a poet in the Italian (Tuscan) language, was given a castle in Pesaro on account of his military prowess, after he had conducted embassies to both great Britain and Rome. While he was working at the Spanish court on behalf of Clement VII, he drew up the Book of the Courtier for the education of the nobility; and in short, after Emperor Charles V had elected him Bishop of Avila, he died at Toledo, much honored by all the people. He lived fifty years, two months, and a day. His mother, Luigia Gonzaga, who to her own sorrow outlived her son, placed this memorial to him in 1529.”

Baldassare Castiglione was the author of one of the most influential work of the Renaissance – The Book of the Courtier (Il Libro del Cortegiano), which deserves a special article dedicated entirely to it. Being himself a courtier and diplomat for years, Castiglione created an instruction about how to be a successful and perfect courtier, what a Renaissance courtier should know and how they ought to act. The Courtier is written in the form of an imagined dialogue that took place over 4 evenings at the court of Urbino in 1507. The participants include 19 gentlemen and 4 ladies, as well as churchmen, scholars, and aristocrats – they were all known to Castiglione from his own time at Urbino. The main topic is “the character and the particular qualities needed by anyone” to be a perfect courtier. Castiglione admitted that highborn people could be wicked, while humble people could become perfect courtiers and accomplish a lot. The perfect courtier must possess a range of virtues: courage, audacity, loyalty, good humor, good manners, grace, as well as skills in combat, riding, sport (hunting, tournaments, and tennis), parlor games, and so on.

Most importantly, Castiglione wrote of the perfect courtier:

“I’ve discovered a universal rule which applies y more than any other in all human actions or words: namely, to steer away from affectation at all costs, as if it were a rough and dangerous reef, and (to use perhaps a novel word for it) to practice in all things a certain nonchalance (sprezzatura) which conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless. I’m sure that grace springs especially from this, since everyone knows how difficult it is to accomplish some unusual feat perfectly, and so facility in such things excites the greatest wonder; whereas, in contrast, to labor at what one is doing and, as we say, to make bones over it, shows an extreme lack of grace and causes everything, whatever its worth, to be discounted. So we can say that true art is what does not seem to be art; and the most important thing is to conceal it, because if it is revealed this discredits a man completely and ruins his reputation.”

The ideal female courtier should be reserved, gracious, elegant, educated, and beautiful, in line with the Renaissance principles. Although an early draft of the Courtier was penned quickly, it underwent substantial rewritings and revisions throughout Castiglione’s life. The book was published in Venice only in 1528, the year before the author’s death. The book went through more than 100 editions by the end of the 16th century and was translated into Spanish by 1534, French by 1537, English by 1561, Latin by 1561, and German by 1565. Emperor Charles V presumably kept at his bedside 3 books: the Bible, Castiglione’s Courtier, and Machiavelli’s Prince.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville