Let’s speak about genealogy. Count Charles d’Angoulême was not as highly inbred as many of his Valois cousins were. However, how was the count related to his wife, Louis de Savoy?

Louise de Savoy was the eldest daughter of Philippe II, Duke of Savoy and his first wife, Marguerite de Bourbon. Her brother – Duke Philibert II of Savoy – succeeded her father, but he died soon, and in turn, the next duke was their half-brother – Duke Charles III of Savoy. As Louise was a Bourbon on her mother’s side, she and her husband, Charles, were most definitely related. Yet, how close their blood connection was? They did have two healthy children – Marguerite d’Angoulême (future Queen of Navarre) and François (future King François I of France).

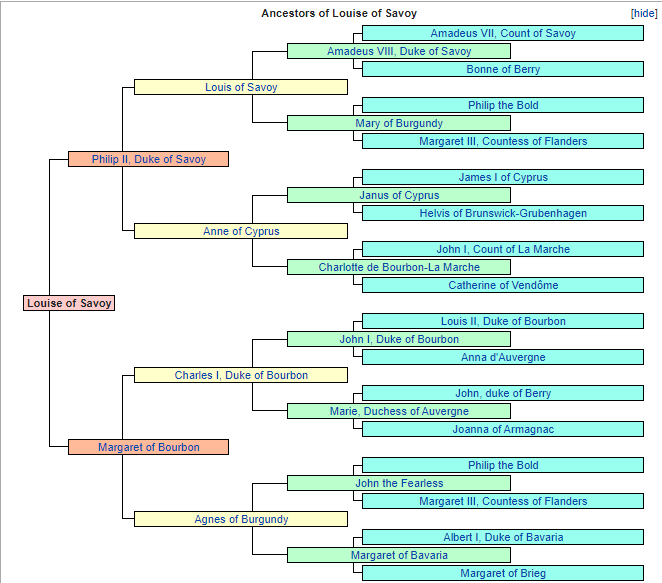

Marguerite de Bourbon, Louise’s mother, was a daughter of Charles I, Duke de Bourbon, and his spouse, Agnès of Burgundy. At the same time, Agnès was a daughter of Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, who belonged to the Valois Burgundian line. Louise’s father was one of the many children of Duke Louis of Savoy and Anne de Lusignan, who had brought fresh blood to their progeny. Louise’s great-grandfather on paternal side was Amadeus VIII, Duke of Savoy, who was descended from Bonne de Berry (a daughter of Duke Jean de Berry, the third son of King Jean II of France and Bonne de Luxembourg). Louise’s great-grandmother on maternal side was Marie of Burgundy, one of the 9 children of Philippe the Bold (the youngest son of King Jean II).

Thus, Louise de Savoy was descended on both paternal and maternal sides from King Jean II of France. Thanks be to God that some new blood was poured into the progeny born as a result of the many dynastic cousin marriages between representatives of the House of Valois, including the Burgundian cadet branch of the Valois family, and the ducal dynasty of Savoy.

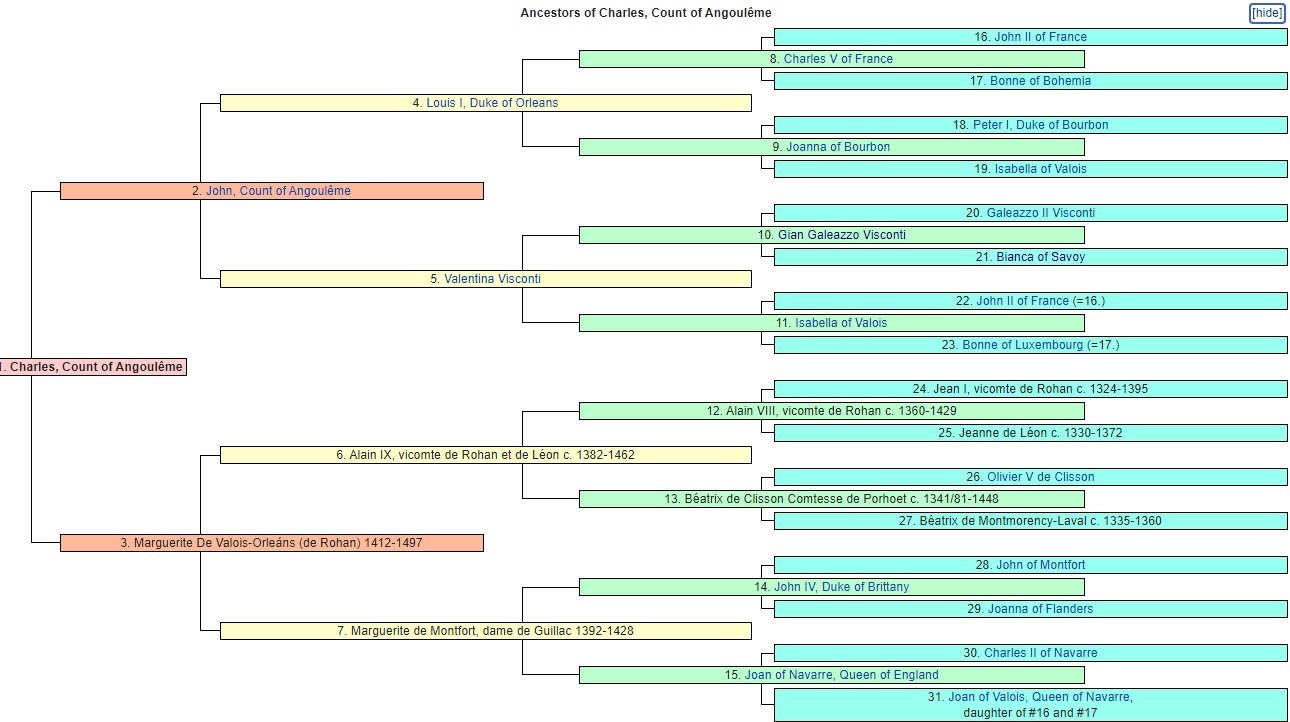

Charles d’Angoulême was descended from King Jean II of France on paternal side. Jean d’Angoulême, his father, was a grandson of Charles V of France, who was the oldest son of King Jean II. Marguerite de Rohan, the mother of Charles d’Angoulême, also had a Capetian blood in her veins, but Jean and his wife were distantly related. From the biological standpoint, Charles d’Angoulême was less inbred than his wife, Louise. However, Charles and Louise were direct descendants of King Jean II, but their bloodlines had not intersected for several generations before their marriage. Sharing the bloodline starting from King Jean II of France and down to Hugh Capet and Charlemagne, Louise and Charles were approximately 4 or 5th cousins once removed.

It was quite a distant relationship for dynastic marriages according to the standards of the time. Perhaps it was one of the main reasons why their offspring – Marguerite de Navarre and François de Valois – were healthy, intelligent, and lived quite long, energetic lives. The Valois- Orléans-Angoulême line was less inbred than the Valois more senior lines.

In the winter of 1496, Charles went out riding and caught a severe cold. After several days of suffering in the grip of a fever, he passed away on the 1st of January 1496, in spite of his wife and his mistress Antoinette’s attempts to nurse him back to health. Louise was widowed at the young age of 19, and she was distressed, mourning for her husband together with Antoinette.

What if Charles had not died and lived a longer life? In this case, taking into account that King Louis XII of France had no surviving sons, he could have ascended to the throne in 1515 at the age of over 50. Charles would not have ruled for long, maybe for a decade. François would have become Dauphin François and would have succeeded his father in due time. But what if Louis XII had breathed his last earlier, between 1500 and 1505? Then the Count d’Angoulême would have been crowned King Charles IX with Louise as his queen consort, and he would have ruled for longer than a decade, maybe for 15-20 years, given that his father had died at 67. Not being very inbred, Charles was in a good health, and it was a serious fever that had killed him.

How would Charles d’Angoulême have governed France? He did not have outstanding military talents. Judging by his unwillingness to participate in Charles VIII’s expedition to Italy, it is logical to assume that Angoulême would have avoided wars, trying to use diplomacy to accomplish his goals. He would have focused on the centralization of the French realm, just as later François I would do. This could have been achieved through strategic marriages between his own offspring and French nobles. If the count had lived longer, he would have had more children with Louise. Due to the fear of marrying foreign brides in the Valois family after Isabeau of Bavaria’s misdeeds, Charles could have arranged a marriage for François within his own family, perhaps to Claude de France if she had existed, to Suzanne de Bourbon (the daughter of Anne de France and Duke Pierre II de Bourbon), or to another Valois or Bourbon princess.

Nevertheless, Dauphin François could also have been married off to an Italian high-profile aristocrat, given that Charles d’Angoulême and Louise de Savoy loved Italy. Moreover, Charles was a descendant of Valentina Visconti, having the claim to the Duchy of Milan. As for his relationship with England, Charles was unlikely to forget his own father’s long captivity, and the shadows of the Hundred Years’ War were hanging over France for centuries. As King Henry VII of England did not invade France, Charles could have signed a treaty with England, perhaps with some betrothals, but he would have always been wary of his northern neighbor.

What would Louise de Savoy’s role as queen had been like? Undoubtedly, Charles would not have been willing to part with his many mistresses; he was accustomed to his wife’s tolerance. The position of maîtresse-en-titre – the chief paramour of a French ruler – would have appeared a decade earlier than it happened in history when François I of France proclaimed Françoise de Foix, Countess de Châteaubriant, his official mistress in 1516. In an alternate reality where Charles d’Angoulême inherited the crown, his favorite lover Antoinette de Polignac could have become his maîtresse-en-titre, having her own apartments at all royal châteaux. As the count’s bastards shared Château de Cognac with his wife and his legitimate children in real history, his bastards would have been brought to court and raised together with Marguerite and François.

Louise would have endured her husband’s eccentric escapades with equanimity, either a real one or a fake one. She would have welcomed her lustful spouse to her bed whenever the count wished, focusing on her queenly duties, raising her own progeny, and continuing her patronage of the arts in the same way as she acted in history after Charles’ demise. Charles was a passionate man, so he would have taken new lovers, and over time, young beautiful girls would have climbed to the acme of a courtesan’s career at the Valois court – the king’s maîtresse-en-titre. Charles was likely to have more illegitimate children, who could have been acknowledged or not.

Charles and Louise’s relationship would have become more official. They would have had to comply with ceremonies, but Charles proved to be a man who did not abide by those rules that he did not like. As they were partners in their marriage while he was alive, we can expect the same in their reign. Therefore, Louise and Charles would have been partners as king and queen, almost co-monarchs. Charles would have appreciated Louise’s political acumen and her counsel, which she proved in real history when she ruled France alongside her son, François, until her death in 1531. Louise could have appeared on meetings of the Privy Council, voicing her opinions. She could have served as her husband’s regent in his absence, although Charles was a man of peace and was unlikely to wage wars unless he had to defend the realm from external threats.

The count trusted his wife a lot. In history, it is proved in his will: Charles d’Angoulême appointed Louise, not any other male relative, the guardian of his children and the administrator of his lands until François came of age. The same would have happened in the scenario of Charles’ kingship. Charles could have allowed his wife to rule alongside him, especially as he aged and discovered more talents and skills in Louise. King François I appears to have inherited his amorous temperament and his appreciation of female intelligence from his father. Louise and Charles would have been a less traditional royal couple compared to King Louis XII and Anne of Brittany.

Louise de Savoy and Charles d’Angoulême could have created the French Renaissance a decade or so earlier than François I did it in actual history. Because of his propensity to collect manuscripts, Charles’ model of kingship would have resembled that of his ancestor, Charles V of France – the first French monarch who was spectacularly educated and passionate about books. Charles V had been a bibliophile and a high-profile political leader, but he also knew how to apply his passions in politics to reinforce the legitimacy of the Valois dynasty during the Hundred Years’ War. In a similar way, Charles d’Angoulême would have continued collecting manuscripts, enlarging the royal library. Angoulême would have used his hobby of collecting books to illustrate the necessity of getting a stellar education for royals and aristocrats, just as Charles V had done. Just as Charles V had rebuilt the Louvre Palace and other castles, Angoulême could have become a builder-king, remodeling and refurbishing existing royal châteaux in the Reaissance style for his comfort and for the reinforcement of the idea that his kingship was tied to culture and peace.

To sum up, Charles d’Angoulême’s kingship would have been based on clever governance and education, not on conquests and the pursuit of glory, which distinguished him from his son – François I who would battle against Emperor Charles V for most of his reign. Charles and Louise would have known that their country, which had economically recovered from the consequences of the devastating confrontation with England by 1500, needed a fresh cultural touch, and Italian artists would have been invited to France much earlier. As Louise loved painting and sculpture, she would have established connections with Italian artists, offering them lucrative commissions to come to France, and many would have accepted such proposals. Charles and Louise – partners in marriage and rulership – would have used the arts for political purposes in a smart way – to highlight the might of the Valois dynasty that had won the Hundred Years’ War.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2021 Olivia Longueville

I love this thanks!

You are welcome! I am glad that you like this article.