The late Renaissance poet Jean Antoine de Baïf was born on the 19th of February 1532 (died on the 19th of September 1589). A member of the Pléiade, he headed this literary group together its chief members such as Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay. These men met at the Collège de Coqueret, where they studied under the Hellenist and Latinist scholar Jean Dorat.

What was the Pléiade? This group of talented literary artists aimed to rejuvenate the classical arts and insisted on the necessity of a demanding poetry in the vernacular. The style of these writers was high-handed and elaborate in contrast to that of their predecessors – the Grands Rhétoriqueurs and the Marotic poets. The Grands Rhétoriqueurs were a group of poets from 1460 to 1520 working in Northern France, the Low Countries, and Burgundy, whose poetry was ostentatious because of the application of exceedingly rich rhymes and unusual assonances and puns. The poetic output of the Marotic poets is connected with that of the illustrious French Renaissance poet Clément Marot, and the style of such poets was light and graceful, like Marot’s style.

Why are the poets from the Pléiade important? Joachim du Bellay created a set of rules for the poets of this direction in his book ‘Défense et illustration de la langue Françoise’ (The Defense & Illustration of the French Language), which was published in 1549. The poets from this group insisted that the French should be enriched by the words, language constructions and literary forms taken from the classics and from the works of the Italian Renaissance. Among them, they advocated to include in French literature the Pindaric and Horatian ode, the Petrarchan sonnet, the Virgilian epic, and other Italian literary forms. Du Bellay and his friends liked archaic French words, which, I must say as a whiter, is quite questionable because many people don’t understand archaic words without a vocabulary. One of their achievements was that they incorporated into their poetry phrases from provincial dialects. They revived the Alexandrine verse form that consisted of 12-syllable lines, rhyming in alternating masculine and feminine couplets.

Born in Venice, Jean Antoine de Baïf was a natural son of the scholar Lazare de Baïf, who acknowledged the boy and gave him a stellar education. Baïf basked in the environment of fine arts in childhood. Later, he studied Latin under Charles Estienne, and Greek under Ange Vergèce (the Cretan scholar and calligraphist who designed Greek types for King François I). At eleven, Baïf became a pupil of Jean Daurat (a French poet, scholar and a member of the Pléiade). It was the time when Ronsard started sharing his studies, and soon they began thinking about the poetry and ways to improve it by turnings their heads towards the antiquity and the Italian Renaissance.

Given the extent of the young man’s knowledge, Du Bellay described him as:

“docte, doctieur, doctime Baïf.”

This mean in the English language something like:

“learned, academic, expert Baïf.”

Baïf was a very talented and prolific poet and writer. He created a huge number of volumes of short poems written on romantic or congratulatory themes. In order to realize how to improve the French language and his own verses, he read and translated numerous excerpts from Bion of Smyrna, Theocritus, Anacreon, Catullus, Martial, and works of other classics. Residing in Paris, Baïf was frequently invited to the Valois court by King Henri II, King François II, King Charles IX, and King Henri II of France. Baïf was favored by Catherine de’ Medici, who backed his and Joachim Thibault de Courville’s idea to found the Académie de Poésie et de Musique (The Academy of Poetry and Music) with the goal to re-establish the lost connection between music and poetry. Within this academy, Baïf worked with popular composers of the late Renaissance such as Claude Le Jeune (a Franco-Flemish composer, and of the Parisian chanson) and Jacques Mauduit (a French composer who combined voices and instruments in new ways on the basis of the Venetian grand polychoral style). These composers put to music some of Baïf’s poems.

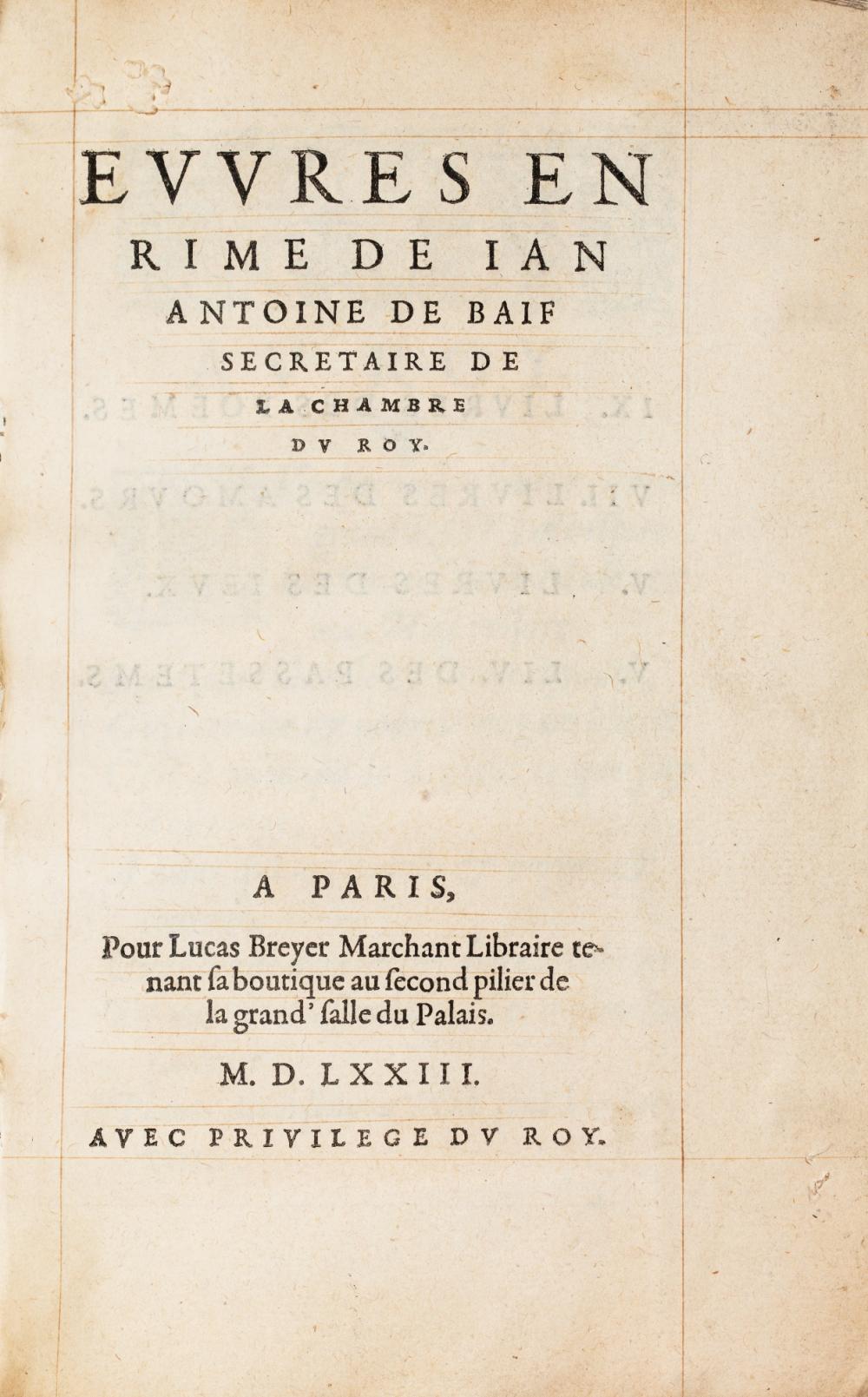

In total, Jean-Antoine de Baïf created over 15,000 measured verses, which all have a special place in the Renaissance literature. His works were published in 4 volumes entitled Euvres en rime (1573), consisting of Amours (Loves), Jeux (Games), Passelemps (some specific name), and Poemes (Poems). Baïf invented a system for regulating French versification by quantity as in ancient poetry, which is known as vers mesurés, or vers mesurés à l’antique. Other poets also experimented with poetry in the same way, but Baïf was perhaps the only one who successfully and gorgeously applied the metrical innovations to music, and the result was the creation of something principally new. Unlike many, he successfully imported Greco-Latin metrics and rhythms into his poetical output. Baïf invented a new system of phonetic spelling; one of such innovations is something that I admire a great deal – a line 15 syllables known as the vers Baïfin.

One of my favorite verses by this artist ‘Du Printemps’ (Spring). It was written for the pleasure of royal courtiers, describing spring in a dream-like, light, and allegorical style.

La froidure paresseuse

De l’yver a fait son temps :

Voicy la saison joyeuse

Du délicieux printemps.

La terre est d’herbes ornée,

L’herbe de fleuretes l’est ;

La fueillure retournée

Fait ombre dans la forest.

De grand matin la pucelle

Va devancer la chaleur

Pour de la rose nouvelle

Cueillir l’odorante fleur ;

Pour avoir meilleure grace,

Soit qu’elle en pare son sein,

Soit que présent elle en face

A son amy de sa main ;

Qui de sa main l’ayant uë

Pour souvenance d’amour,

Ne la perdra point de vuë,

La baisant cent fois le jour.

Mais oyez dans le bocage

Le flageolet du berger,

Qui agace le ramage

Du rossignol bocager.

Voyez l’onde clere et pure

Se cresper dans les ruisseaux ;

Dedans voyez la verdure

De ces voisins arbrisseaux.

La mer est calme et bonasse ;

Le ciel est serein et cler ;

La nef jusqu’aux Indes passe ;

Un bon vent la fait voler.

Les menageres avetes

Font çà et là un doux fruit,

Voletant par les fleuretes

Pour cueillir ce qui leur duit.

En leur ruche elles amassent

Des meilleures fleurs la fleur :

C’est à fin qu’elles en facent

Du miel la douce liqueur.

Tout resonne des voix nettes

De toutes races d’oyseaux :

Par les chams des alouetes,

Des cygnes dessus les eaux.

Aux maisons les arondelles,

Aux rossignols dans les boys,

En gayes chansons nouvelles

Exercent leurs belles voix.

Doncques la douleur et l’aise

De l’amour je chanteray,

Comme sa flame ou mauvaise

Ou bonne je sentiray.

Et si le chanter m’agrée,

N’est-ce pas avec raison,

Puis qu’ainsi tout se recrée

Avec la gaye saison ?

The artist’s verse can be translated into English:

The indolent cold

Of winter has run its course;

Now is the joyous season

Of beautiful spring!

Grass adorns the earth

And flowers the plants;

Foliage has returned

To shade the forest.

The maiden in early morn

Goes out before the heat

To pluck a fragrant flower

From the newly opened rose

In order to enhance her grace,

Be it upon her breast

Or be it presented

To her swain,

Who, taking it from her hand

For remembrance of love,

Will not lose it from sight

But kiss it a hundred times each day.

But hear the shepherd’s flute

From over the hedgerows

Disturbing the nightingale

That nests in the copse!

See the clear, pure waters

Ruffling through streams

Between the greenery

Of the neighboring shrubs!

The sea is calm and smooth

The sky serene and clear;

The ship sails away to the Indies

Flying before the fairest of winds.

Here and there, worker bees,

Making sweet fruit,

Flutter through flowers

To gather their produce.

In their hives is nectar

Garnered from the best of flowers

In order to make

Sweet syrup from honey.

All resounds with clear voices

From every breed of bird:

Larks in the fields;

Swans on the waters;

Around the houses, the swallows,

Nightingales in the wood,

Gaily singing new songs

Performed with beautiful voices.

It is of the sorrow and pleasure

Of love that I sing,

Feeling its flame,

Whether painful or sweet.

And, if I find my singing agreeable,

Have I not reason

That I may, thus, be amused

By this merry season?

Personally, I love romantic poems far more than anything else. However, we also have to say that Jean Antoine de Baïf wrote not only beautiful poems in his quite elaborate style for good mood pf his audience. He completed the sonnet praising the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, which was perhaps done to please his patroness – Catherine de’ Medici. I focus on his verses for entertainment rather than such controversial sonnets. His version of the Roman de la Rose was popular at the court of Charles IX of France. Baïf also composed two comedies: L’Eunuque (published 1573) and Le Brave (1567). A collection of his verses in Latin was published in 1577.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2021 Olivia Longueville

Hi Olivia, I’ve read quite a few of your posts and would like to thank you for sharing your interest and expertise on the subject. By chance, could you link me to that sonnet praising the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre?

Hello! Thank you for your comment, and I’m sorry for the belated response. I’ve been going through a highly stressful year of my life following my father’s death, and so many things, including my online activities, have literally stopped for me.

Hello and thank you for your kind words about my article. I hope to be back to FB and Twitter as soon as I can. If you want to find some Jean Antoine de Baïf’s sonnets and other works translated into English, you can try to use this source:

https://www.poemhunter.com/jean-antoine-de-baif/