King Jean II of France known as the Good (le Bon) was born on the 16th of April 1319 at Château du Gué-de-Maulny near Le Mans, in France. Given the horrendous troubles his reign brought to France, I think that he should be known not as the Good, but as the Troublesome (le Problemàtic), the Arrogant (l’Arrogant), or perhaps even the Unfortunate (le Misérable). He was the oldest son of Philippe de Valois and his first cousin-wife, Jeanne of Burgundy, also known as Jeanne the Lame (Jeanne la Boiteuse). We have little information about Jean’s childhood.

At the time of his birth, Jean’s father was only the son of Count Charles de Valois, a younger brother of King Philippe IV the Fair. A powerful magnate and a competent royal councilor, Charles was an uncle of the last 3 direct Capetian rulers – King Louis X the Quarrelsome (le Hutin), King Philippe VI the Tall (le Long), and King Charles IV the Fair (le Bel). Count Charles de Valois was a relative to the short-lived son of Louis X with Clemence of Hungary – Jean I the Posthumous (Ier le Posthume). Maybe the choice of the name Jean was rather unfortunate for the boy, and later, there will be no happy princes and monarchs named Jean in the history of France.

During their long marriage, Philippe de Valois and Jeanne of Burgundy had many children. Jeanne birthed 8 more children after Jean, but only her son Philippe (born in 1336, one year before the beginning of the Hundred Years War) survived. Why did only 2 out of their vast progeny live into adulthood? Most of these hapless offspring were born sickly and fragile, or they were stillborn. No one understood the detrimental effect of inbreeding on progeny and its survival rates back then, and marriages for royals and aristocrats were arranged for dynastic purposes.

Daughter of Duke Robert II of Burgundy and Agnes of France, Jeanne the Lame was a granddaughter of Louis IX of France called Saint Louis and his consort, Marguerite de Provence. Son of Charles de Valois and his first wife, Countess Marguerite d’Anjou, Philippe de Valois was a grandson of King Philippe III of France the Bold (le Hardi) and his first spouse, Isabella of Aragon. This makes Philippe a great-grandson of Louis IX and Marguerite de Provence. Therefore, Jeanne and Philippe were quite closely related. In addition, Philippe was a product of inbreeding: Charles de Valois and Marguerite d’Anjou were double 2nd cousins of Capetian descent. Jeanne’s father, Robert II of Burgundy, was also a descendant of the House of Capet.

One of the reasons why Philippe the Fair’s 3 sons could not produce male progeny could be that by the end of the 13th century and the first decade of the 14th century, most marriages within the French royal family were highly consanguineous. The senior Valois male line was no less inbred than the Capetian line that died out with the passing of Charles IV of France in 1328. It is no wonder that Jeanne the Lame produced many sickly and stillborn babies, much to her and her husband’s grief. Jean’s only surviving brother was 17 years his junior, born when Jeanne was already 42-43; unfortunately, Philippe would die at 39 in a childless marriage.

Against all odds, Jean survived into adulthood and became the heir to France when his father ascended to the throne as King Philippe VI of France the Fortunate (le Fortuné) in 1328. The Salic law prohibiting the inheritance of the French throne by women and male descendants of women can be traced back to Merovingian era, but after the termination of the direct Capetian line, it became especially important and was applied on purpose. King Edward III of England, a grandson of Philippe the Fair through his mother, Isabella of France, was the closest male relative through female bloodlines, but no Frenchman wanted to make France a province of England. Besides, Philippe de Valois was Philippe the Fair’s nephew, so the choice for the French was obvious, in particular given the old Merovingian Salic law established in the legislation of King Clovis I.

As Philippe’s heir apparent, Jean was created Duke of Normandy in 1332. He also became Count of Poitiers in 1344 and Duke of Aquitaine in 1345. To consolidate his power in France and gain a new alliance, Philippe VI married the 13-year-old Jean off to the 17-year-old Bonne of Bohemia (Bonne de Luxembourg). She was slightly older than Jean and of childbearing age. Bonne’s dowry amounted to 120,000 florins, and according to their marriage contract, in the event of war with England or someone else, Bohemia would have to provide the French army with 400 infantrymen. It was a good alliance for Philippe VI, but it was also an excellent marriage from a genetic standpoint. Daughter of King Jean of Bohemia and Elizabeth of Bohemia, Bonne was not closely related to Jean. This brought the much-needed fresh blood to their progeny and allowed their 6 out of 10 offspring to reach adulthood, including King Charles V of France called the Wise (le Sage), Duke Jean de Berry, and Philippe the Bold (le Hardi), 1st Valois Duke of Burgundy.

As Duke of Normandy, Jean had to deal with the political instability in the region. The duchy had been conquered by King Philippe II Augustus over 150 years ago, so the economic and social relations between France and Normandy were established. However, due to the claims of Edward III of England and some inner instability, many Norman aristocrats allied with the English camp. The region highly depended economically on maritime trade across the Channel with England. Thus, Jean governed Normandy in accordance with his father’s advice: he provided many nobles and cities with charters guaranteeing the duchy a lot of autonomy. The Norman nobles formed two warring factions: the counts de Tancarville and the Counts d’Harcourt.

Geoffroy d’Harcourt waged war against King Philippe VI, and a number of lords supported him. The rebellion was massive with the demand to make Geoffroy Duke of Normandy instead of Jean. The royal troops crushed them: Geoffroy was exiled to Brabant, and some of his men were beheaded in 1344. Later, Philippe sent his son to Geoffroy d’Harcourt to make peace, and he arranged the marriage of Jean, Viscount of Melun, to Jeanne, the only heiress of Tancarville, which ensured that after Philippe’s death, the Melun-Tancarville faction was loyal to France and Jean II. Geoffroy d’Harcourt remained the main opponent of King Jean II in Normandy.

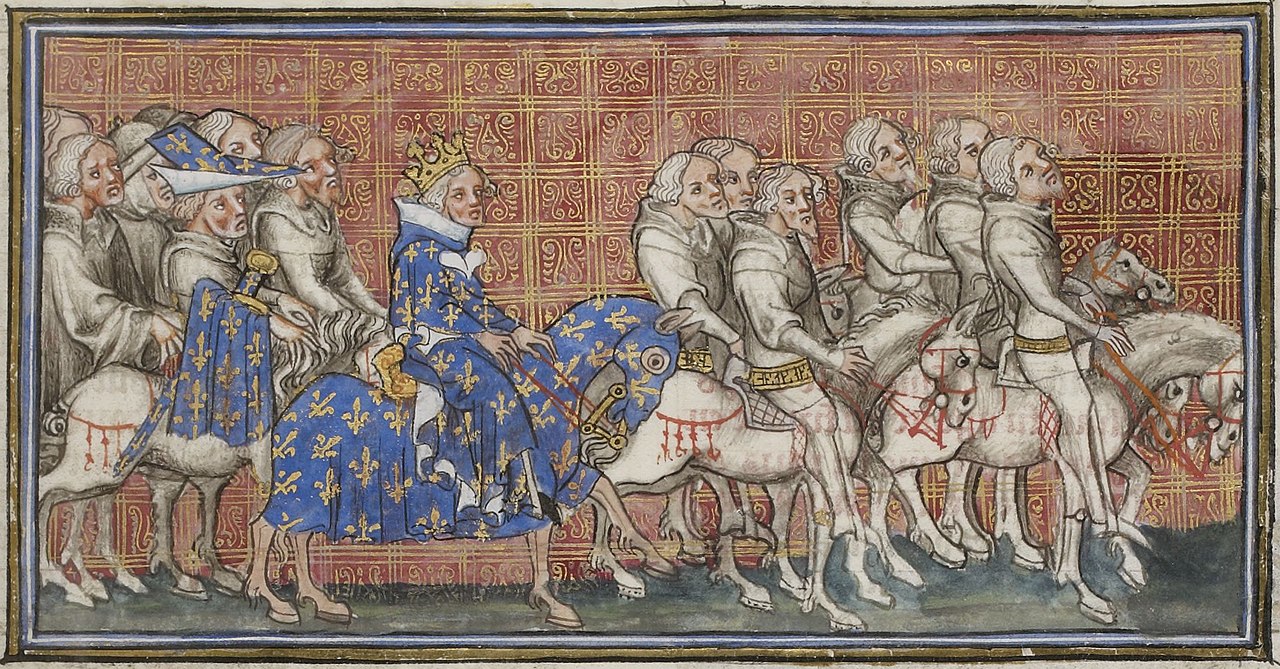

Jean de Valois succeeded his father in 1350 after King Philippe VI had died of the plague. On the 26th of September 1350, he was crowned at Reims as King of France, becoming the 2nd Valois monarch. By that time, Jean was a widower: Bonne de Luxembourg had passed away of the plague in 1349, one year before she could become Queen of France. On the 19th of February 1350, Jean remarried Jeanne I, Countess d’Auvergne and de Boulogne. Jean, who seemed to have almost no emotional attachment to Bonne, quickly moved on and added more titles to his collection – he became Count d’Auvergne and de Boulogne through his union with Jeanne.

Jeanne d’Auvergne was crowned Queen of France. She was a daughter of William XII, Count d’Auvergne, and Marguerite d’Évreux, who belonged to the House of Évreux that was the cadet branch of the House of Capet. William d’Auvergne the eldest son of Robert VII d’Auvergne and Blanche de Bourbon, daughter of Robert, Count de Clermont – the youngest son of Louis IX of France. Sometimes, these circles of consanguinity or inbreeding circles, as I call them, might be confusing, and they can shock modern people, but back then, it was an ordinary thing. Jean and Jeanne had 3 children, but all of them died shortly after birth.

Jean’s second marriage was much worse from a genetic standpoint. Yet, it also allowed him to become a guardian of Jeanne’s son: Jeanne was the widow of Philippe of Burgundy, the dead heir of this duchy, and their only son was Philippe I, Duke of Burgundy. Jean’s stepson died at only 17 in 1361. The above allowed the monarch to make his youngest and favorite son Philippe the Bold royal lieutenant-general and Duke of Burgundy in 1364. Jean II of France helped his son, Philippe, become the founder of the Valois-Burgundian dynasty, which would later cause a lot of grief to the descendants of Jean’s oldest son – King Charles V of France.

However, the establishment of the Valois rule in Burgundy was one of Jean II’s very few accomplishments. After his ascension, Jean removed the old advisors of his father, claiming that they discredited the monarchy by mismanaging the realm. Indeed, the reign of Philippe VI was plagued with troubles: the Hundred Years’ War, the devastating defeat of the French at the Battle of Crécy of 1346, and pandemics of the Black Death in the 1340s. Yet, if we look at Philippe VI’s actions and decisions, we can infer that he was quite an adequate and capable monarch, one who was nevertheless beset with misfortunes, many of which were not caused by him.

Philippe VI’s first consort, Jeanne the Lame, was a smart woman who acted as regent in his absence and when he was fighting his wars. Jean II of France had neither a capable regent nor the intelligence, resilience, and strength of his parents. Jean’s administrators were barely competent, who together with their liege lord preferred to enjoy a luxurious life at court with festivities and hunts rather than being engaged in state affairs. Even when later in his life Jean took over more of the administration himself, it proved to be disastrous as he alienated nobles with his overbearing, arrogant, and impulsive manner of decision making and treating his subjects.

One of Jean II’s opponents was his cousin – King Charles II of Navarre called the Bad (Le Mauvais). Charles possessed not only his small Navarrese realm, but also lands in Normandy. In 1354, the ruler of Navarre was complicit in the murder of Charles de la Cerda, Constable of France. To avoid Charles’ alliance with England, Jean signed the Treaty of Mantes with his cousin. Jean was not a forward-looking monarch: the King of Navarre soon allied with Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster. Jean should have been taught not to trust Charles the Bad, but instead he signed another meaningless Treaty of Valognes in 1355, which did not last long either.

Perhaps due to his inherent inbred genes, King Jean did not have good health. He was a sickly man despite his tall height and his relatively large size, so he preferred a court life and was not a warrior. According to some chronicles, Jean was considered quite handsome. Charles de la Cerda was Jean’s absolute favorite, and there were rumors that they ere lovers. It cannot be proved, but after La Cerda’s death, Jean was grief-stricken more than a king should be. The historical parallel to the murder of La Cerda is that of Edward II of England’s Piers Gaveston.

King Jean II of France can be summed up in these words: intemperate, haughty, irrational, impulsive, overbearing, and lacking intelligence to make strategic decisions. Many unnecessary treaties, favorites and grants of lands to them, festivities instead of ruling the realm, incompetence in the management of his nobles… Nonetheless, the apogee of his horrible rule was his personal responsibility for the catastrophic defeat of the French troops at the Battle of Poitiers on the 19th of September 1356. Jean was advised not to fight an open battle against Edward, Prince of Wales (the Black Prince), and to have the English surrounded and starved in Poitou. Despite the counsel of his generals, especially the insistent advice of Gauthier VI de Brienne, Constable of France, and Jean de Clermont, Marshal of France, the king was so overconfident in his victory that he did not listen to anyone. Totally unreasonable!

I wrote an article about King Jean II’s defeat at Poitiers and his merry captivity in England. You can find access to it here: https://olivialongueville.com/2020/09/18/unfit-to-rule-the-merry-captivity-of-king-jean-ii-of-france-after-the-battle-of-poitiers-of-1356/

Jean was unfit to rule. His incompetence led him to Poitiers and then into the hands of the English, but he lived in luxury during his captivity. At the same time, his realm was bleeding out, while his son, Dauphin Charles (future Charles V of France) had to deal with revolts and Charles the Bad, and the dauphin had to collect the astronomical ransom of 3,000,000 crowns for his father. According to the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360, France lost a vast number of lands, including Guyenne, Gascony, Poitou, Saintonge, Périgord, Limousopn, Aunis, Agenais, Quercy, Bigorre, Gauré, Angoumois, Rouergue, Montreuil-sur-Mer, Ponthieu, Calais, Sangatte, Ham, and Guînes. It was almost 1/3 of the territory of France back then – and it was sacrificed to have Jean released.

On the 8th of July 1360, Jean II of France appeared in the English-controlled Calais. His second wife, Queen Jeanne, died on the 29th of September 1360 soon after his return. Surprisingly, he did not search for a new bride, for he was a man active in the bedroom. Jean returned to his old practices of arrogant and irrational ruling, painting himself absolutely incompetent in comparison with Dauphin Charles, whose efforts rescued him from captivity. Many festivities were organized at court. Meanwhile, Jean’s sons – Louis I, Duke d’Anjou and Jean, Duke de Berry – together with Jean’s brother – Prince Philippe, Duke d’Orléans – and many nobles, as well as 2 citizens from each of the 19 principal towns of France languished in English captivity as hostages. France paid most of the ransom for Jean, but not everything.

In July 1363, the troublesome monarch was informed that Louis d’Anjou had escaped. An incensed Jean shouted at his advisors and relatives that his son had humiliated him and repudiated principles of chivalry. It must have been a bizarre and doleful spectacle at the Valois court. Jean decided to return to England in order to save his honor, although everyone attempted to dissuade him. Jean never listened to anyone and sailed for England in the winter of 1363. Of course, King Edward III of England and Edward the Black Prince welcomed him with celebrations in England, but they must have laughed at France and her monarch behind Jean’s back.

King Jean II humiliated France many times. He insulted the Valois monarchy, making himself and his family a laughingstock of Europe. He did not care that his relatives were shocked, and his subjects were impoverished after the payment of the vast part of his ransom. Bizarre, sad, and unbelievable that a ruler could behave so! Jean died in London on the 8th of April 1364, and I’m not ashamed to say that his demise was a good thing because his successor was Charles V the Wise, who would liberate France from the English, giving stability and prosperity to the country.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2021 Olivia Longueville