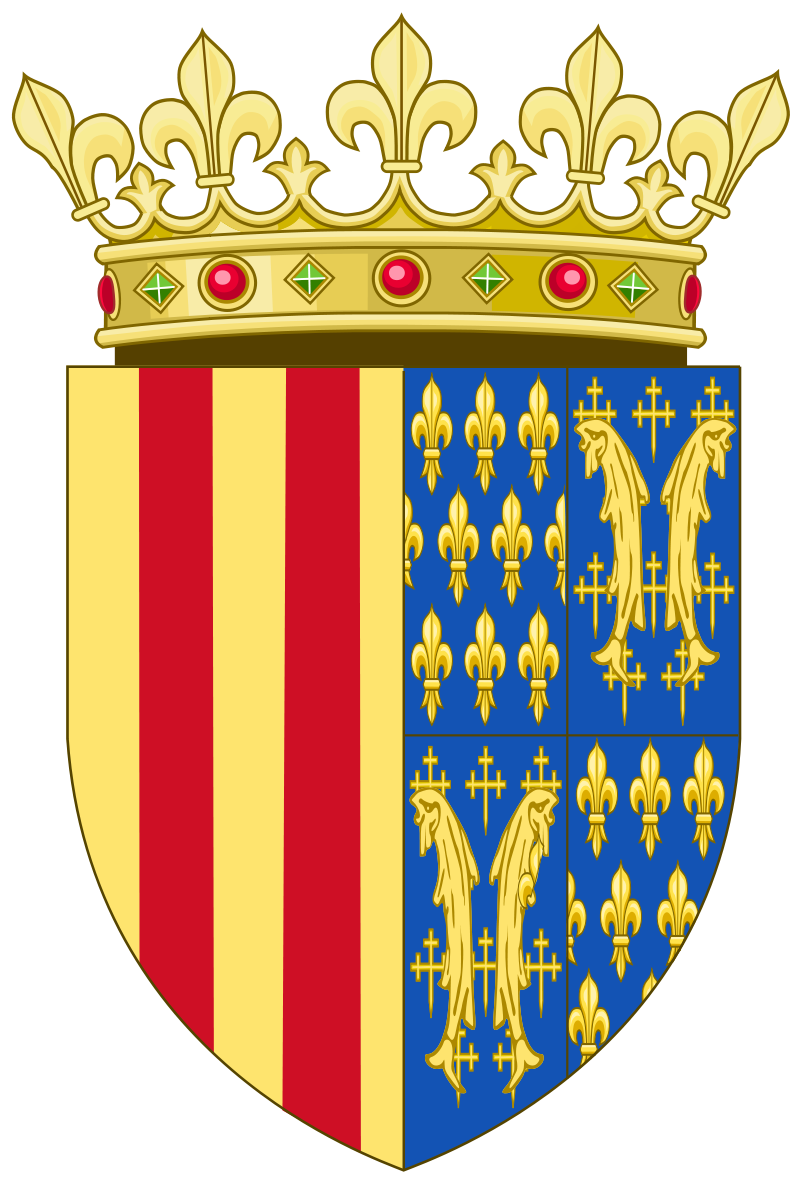

Yolande of Aragon was born on the 11th of August 1384 in Zaragoza, in Aragon. She was the only surviving daughter of King Juan (or John) I of Aragon (born in 1350) and Violant (or Yolande) de Bar (born c 1365). In order not to confuse mother and daughter, I shall call young Yolande (in her adulthood Duchess d’Anjou and Countess de Provence by marriage, as well as titular Queen of Sicily) by this name and her mother, Queen Violant of Aragon, Violant.

Her mother was the 8th of 11 children of Robert I, Duke de Bar, and Marie de Valois, Princess of France. On her mother’s side, Yolande was descended from King Jean II of France called the Good (French: le Bon). Perhaps the Valois blood coursing through her veins predestined her love for France, which caused Yolande’s profound commitment to the country’s liberation form the English in her adulthood. Her maternal grandmother was King Jean’s first wife – Bonne de Luxembourg, Queen of France. On her father’s side, Yolande’s ancestors were from the House of Dampierre that ruled Flanders, the Capetian House of Burgundy, and the Plantagenet family.

Yolande’s father ruled Aragon only for 9 years – from 1387 until his death in 1396. Born in Perpignan, capital of the Rousillon, Juan was the eldest son of Pedro IV of Aragon and his third wife, Eleanor of Sicily. Juan had two surviving siblings: Martin and Eleanor of Aragon. Year later, Yolande’s uncle Martin became her competitor for the throne of Aragon. Juan of Aragon was married twice, but out of his many children born by his wives, only two daughters – Juana (Joanna) born in 1375 and Yolande born in 1384 – survived into adulthood. His first wife was Martha d’Armagnac, and after her death in 1378, Juan remarried Violant de Bar in 1380.

Juan’s marriage to Martha was not very successful in a personal aspect. After her passing, his father wanted for his elder son to marry a Sicilian princess, but Juan wed Violant against his wishes. His second marriage was happy because the spouses had an affectionate relationship and understood each other well. A Francophile, Juan was a man of character, one who loved literature and the arts. Juan was a protector of culture de Barcelona, where he preferred to reside with his court. In 1393, he established the Consistory de Barcelona – a literary academy with the main goal was to promote what was considered correct styles and themes, and also to eliminate vices by awarding prizes to those poets who followed the rules of poetic composition.

King Juan of Aragon was called the Hunter or the Lover of Elegance (Spanish: el Cazador o el Amador de Toda Gentileza). The court of King Juan and Queen Violant was sumptuous and cultured. As both monarchs loved everything French, the queen transformed it into a center of French culture, which blended with Aragonese culture in the best possible way. Juan’s wife shared his tastes in music and literature, and they both patronized Provençal troubadours. Therefore, their daughter Yolande grew up in the midst of impressive luxury and intellectual splendor; the girl received a stellar education. All of their children were short-lived, except for Yolande.

Their court strove to emulate the intellectual court of King Charles V the Wise (French: le Sage) – a highly competent and magnificently educated monarch, one who was a bibliophile and a dedicated book collector. The courts of Robert de Bar and Duke Jean de Berry (a famous patron of the arts) were also intellectual, also serving as a paragon for the Aragonese court. Violant received a refined education at the court of his uncle, Charles V of France, where she seemed to have met with the first French female writer Christine de Pisan. King Juan composed verses, as we learn from his private letters to his brother, Martin. The excerpt from one of them is given below:

“Dear brother! Know that on a recent festivity, looking through some of our choir chants, we composed one song (rondell) with its musical notations and its lyrics, a transcription of which I’m sending to you enclosed in the present letter begging you, dear brother, that you sing it…”

Queen Violant introduced to the Aragonese court the culture of her homeland. She initiated the performance of amusing fictitious “flirts,” courtly love games, the reading and discussions of French literature. Their court was thronged with artists including Bernat Metge (a Catalan Catalan writer and humanist, as well as a translator of Petrarca to Catalan), Andreu Febrer (a diplomat, poet and Spanish translator of Catalan expression), Carroga de Vilaragut (a writer), and many others. Violant commissioned various literature books, as well as translations of French and classical works. Violant was fond of the French poet and musician Guillaume de Machaut, so she was instrumental in spreading his works and making them popular among Aragonese intellectuals. Their daughter, Yolande, tasted this intellectual splendor.

More illustrious people thronged the royal court. Including: Bernat Descoll (a Catalonian administrator and chronicler), Antoni de Vilaregut (a translator of Sĕnĕca and author of other works), Pere d’Artés (a Valencian nobleman, councilor, and translator), and so on. From Yolande’s letters written to her mother from France in adulthood, we learn that Violant read ‘Il Corbaccio’ (The Crow) by Giovanni Boccaccio, and this encouraged writers (Diego de La Vera and others) to compose treatises in the defense of women and their role in the medieval society. It is remarkable that Violant’s grandmother, Bonne de Luxembourg, forced her favorite poet whom she patronized – Guillaume de Machaut – the insulting judgements about women in one of his works.

Actually, the female art patronage during the Middle Ages was one of the first ways try and to fight against the gender biases that still exist even in our modern society. Queen Violant was a cultural ambassador in Aragon. Her influence on Aragonese culture was pervasive, although by the time of her arrival in Aragon, there were already educated nobles who were fond of the arts and welcomed her introductions. Violant and Juan’s fascination of the French courts was criticized by some contemporaries. It is still misinterpreted by some of those who advocate the supremacy of Spanish culture. It is understandable, but in reality, culture of foreign nations always influences national cultures, and their fusion may create something awesome.

Unfortunately, Violant is often portrayed as a vain, extravagant, extremely ambitious, and capricious Frenchwoman, one who controlled her husband, the king, and unnecessarily meddled in state affairs. In the annals of Jerónimo de Zurita y Castro (1512-1580) who was a Spanish government official regarded as the first modern Spanish historian, we find this portrayal of Queen Violant. The same depiction of her – quite unfair – found the way into the writings of Iberian historians such as Prospero de Bofarull y Mascaró (1777-1859), Antoni Rubió i Lluch (1956-1937), Ferran Soldevila (1894-1971), and a few others. Some of them even called Violant overly aggressive. At the same time, the historian Salvador Sanpere y Miquel (1840-1915) studied th he lives and reign of Juan I and Violant de Bar, giving them a favorable assessment.

Salvador Sanpere characterized Queen Violant as:

“She was a woman with a manly soul.”

By calling her so, Sanpere underscored Violant’s strength, abilities, and intelligence. Can’t we say the same about her daughter Yolande looking at Yolande of Aragon’s role in the Hundred Years’ War? Most definitely, we can, in a good way! Queen Violant was referred to as a ‘dona que feya d’homa’ (a woman who acted a man) and a ‘dona varonil.’ King Juan, in contrast to her, is frequently depicted as ‘afeminat’ (effeminate). Violant was much more denigrated than other French princesses and French women not because she was downright a bad person, but because she was a strong and capable female politician, one who wielded substantial power and influence, which was very different from a traditional female role as it was perceived back then.

Yolande of Aragon had intelligent parents, and she could see that women could accomplish prominence at royal courts depending on their intellectual level and qualities. As Juan was often ill, Violant actively assisted him in political and administrative affairs. Violant served as ‘Queen-Lieutenant’ (regent) of Aragon as proxy of her spouse from 1388 until 1395. In this capacity, she acted as an intercessor on behalf of the monarch’s subjects, as a queen dealing with foreign dignitaries, in particular with her extended French family, and as someone who defended her Jewish subjects. Violant embraced all these responsibilities and achieved good results.

In her personal correspondence, Violant often appealed to her husband to moderate some of his harsh orders or punishments. We meet the formula ‘us suplic senyor’ (I beg you, my lord) in her letters to Juan. The queen served as an intermediary between the Crown and Parliament or the Cortes. Juan, who often clashed with the Cortes in certain matters, asked his consort to help him find a compromise, and Violant excelled at this. Her letters to councilors and members of the Cortes demonstrate her erudition. Unlike most of earlier and contemporary rulers, Violant was a staunch supporter and defender of the Jewish populace. One of the reasons was that the Jews helped fill the royal coffers, but Violant was also a compassionate person.

King Juan dedicated more time to hunting, his favorite pastime, and the arts than governance. Because of her position of Queen-Lieutenant, Violant de Bar exercised the sovereignty over Aragon during her husband’s short reign. Those medieval and Renaissance queens who governed the realms of their sons or spouses were often vilified by their contemporaries, becoming objects of nasty rumors. For example, take Catherine de’ Medici in France as an example. Violant was a catalyst for cultural, economic, and political changes in Aragon, which were entrenched in the Aragonese court years before her marriage to Juan, but she facilitated their development. In this aspect, Catherine de’ Medici was perhaps a more revolutionary woman and politician.

At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that the reign of Juan I and his wife Violant was marked by financial and administrative disorder in Aragon. Juan adored his wife absolutely and was not a strong-willed man, so his feelings for her kind of blinded him to the favoritism. This and other factors resulted in political abuse and widespread corruption, which plagued their realm and because of which they are disliked by some historians. The spouses’ excessive extravagance and fiscal corruption emptied the royal coffers, which fueled the negative assessment of their reign and contributed to the creation of Violant’s negative portrayal. Yolande definitely comprehended that the accusations of her parents in profligacy and corruption were not only politically motivated, but also fair – Yolande herself made necessary conclusions and was never associated with

Queen Violant was a royal model for her only daughter, Yolande. From her childhood, the girl observed that a woman was far more than a womb on her legs to carry children. Her mother governed, took care of Iberian subjects and her daughter, patronized artists, and aided her husband in everything. Yolande learned all these things well. The model of her parents’ matrimony when Juan permitted Violant to have autonomy and influence his decisions made Yolande remember that a woman, especially a queen, can make impact on and transform the various landscapes of a country. This invaluable experience shaped Yolande’s personality as that of a smart political player and an energetic woman of action since her early years. Later it would help Yolande tip the balance in favor of the French during the Lancastrian phase of the Hundred Years’ War.

Thanks to his personal preferences and his wife’s influence, Juan I of Aragon conducted strictly pro-French politics, unlike his father’s Anglophile policy. With Juan’s ascension, France found a friend on the Iberian Peninsula; Queen Violant often corresponded with King Charles and later with the regents of King Charles VI known as the Mad (French: le Fou) during Charles VI’s minority. Juan supported the Avignonese Popes during the division of papacies within the Roman Catholic Church (the Western Schism that existed from 1378 to 1417). These important things predetermined Yolande’s support of Avignon in her adulthood until the end of the Schism.

Yolande witnessed her mother’s actions and understood Violant’s confidence that she had the ability and skills to govern. It is logical to assume that having such an outstanding example before her eyes, Yolande became convinced that a woman, if she was strong, smart, and educated, could be almost a ruling queen, a governor, an ambassador, or any political appointee. Having a French mother and a pro-French father, Yolande grew up in a deeply Francophone environment. This caused her to love France as a child, and it would later make her adopt the interests of the House of Valois as her own during the chaos of the war against England. Yolande spoke flawless French from childhood with her mother and her tutors, some of them French.

In 1389, King Juan started marriage negotiations with Marie de Blois, Duchess d’Anjou who was mother of Duke Louis II d’Anjou. Marie herself proposed her son as a potential husband for Yolande, but her proposal was at first rejected. A few years later when Juan was still alive, King Richard II of England sought Yolande’s hand in marriage after the death of his first wife, Anne of Bohemia. King Charles VI of France prevented this marriage by arranging the union of his daughter, Princess Isabelle de Valois, to the English ruler despite the girl’s tender age. No one knew at the time that Louis II d’Anjou would turn out to be Yolande’s fate and her true love.

We do not know a lot Yolande’s early years. Yet, her life in Aragon created her tremendous intelligence, taste, and education, which made Yolande one of the most fascinating women in France’s history. After Juan’s death, his brother Martin assumed the Aragonese throne – he ruled until 1410 as King Martin I of Aragon known as the Humane and the Ecclesiastic. Grudgingly, Violant and Yolande had to accept it until Martin’s death, but years later they tried to fight for the throne, yet unsuccessfully. Violant outlived her husband by many years and spent 35 years as queen dowager until she passed away on the 13th of August 1431 in Barcelona. Violant’s correspondence from this period – to her daughter who lived in France as the wife of Duke Louis II d’Anjou and to others – was tinged with sadness, and she lamented the loss of her crown.

Violant said to the future King Juan II of Aragon long before his ascension:

“We have been queen, and we have held the scepter of this realm, representing the image and body of the lord king, your uncle, of glorious memory.”

Although her union with King Juan was her vehicle to the throne, Violant remained queen in her heart and mind after his demise. It certainly influenced her daughter even when they lived in different countries. Violant saw the great acumen of her daughter which Yolande displayed in France between 1415 and 1430. Violant and Yolande were much alike in politics and their ability to govern, but Yolande nonetheless won the political race with her mother. The family background and early formative years of Yolande of Aragon made her who she later became in history, but Yolande did not repeat her mother’s mistakes (for instance, profligacy), knowing that those who are superior with regards to the virtues possess better abilities to rule and guide.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2021 Olivia Longueville