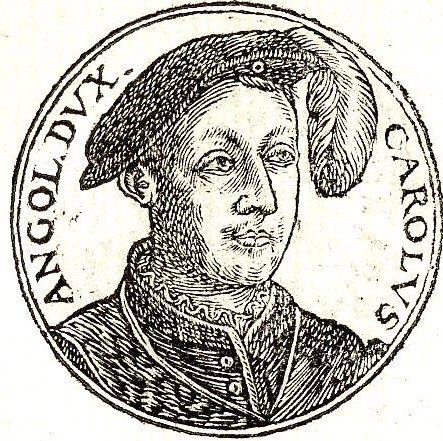

History offers us the lives of many historical figures who are forgotten or almost forgotten, some of them having quite interesting life stories. One of such people is Charles II de Valois, Duke d’Orléans. Born on the 22nd of January 1522, Charles was a 3rd son of King François I of France and his first wife, also his cousin, Queen Claude of France. Until the death of his elder brother – Dauphin François, Duke of Brittany – Charles was known as Duke d’Angoulême.

Child mortality rates were extremely high in the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance era. In royal and noble families, where people often intermarried, many of them were rather inbred, which negatively influenced their life expectancy and health. Unlike many of his predecessors, François I nevertheless could be considered lucky because he had 3 sons with Claude, all of whom lived into adulthood despite their parents being cousins. Both François and Claude were descended from Louis I de Valois, Duke d’Orléans (a younger brother of Charles VI of France known as the Beloved and later as the Mad), and his Milanese spouse, Valentine Visconti.

That François I’s sons would go on to continue the Valois dynasty and François’ legacy was perceived as a given. After Claude’s death, François was soon compelled to remarry Eleanor of Austria following his misadventures during Italian wars and his captivity in Spain. However, François appeared to have considered his line secured, so he did not often visit the bedroom of his second unwanted wife – if he did at all – and did not try to have more children with Eleanor. Had François known the gloomy future of his male descendants, he would have acted differently in spite of his dislike, if not detestation, which he obviously felt towards Queen Eleanor.

François’ first son, his namesake, passed away at the age of 18 in 1536 from some illness, although the circumstances of Dauphin François’ death might be considered somewhat mysterious (the article about his passing). King François’ second son – Henri, initially Duke d’Orléans and eventually King Henri II of France – was married to Catherine de’ Medici, whom he never loved and with whom he failed to sire any children during the first decade of their complicated marriage. François I could not predict that the male line of Henri II would go extinct in less than fifty years after his own death.

So, what about Charles de Valois, François I’s 3rd son? The youngest prince, Charles was not expected to ever inherit the throne, yet his life might become a subject for a novel, especially one written set in an alternate history universe. Resembling his father more than his brothers, Charles was his father’s favorite son, and François I would have preferred Charles to succeed him instead of Henri, but it was not meant to be. If Charles had not died in 1545 and if he had married and had legitimate issue, they would have ascended to the throne in years to come.

After their elder brother Dauphin François’ death, Charles became Duke d’Orléans. He received a title that had previously been held by his elder brother Henri, who had succeeded the unfortunate François as Dauphin. Henri, who had been jailed in Madrid together with Dauphin François for several years, was severely affected by his humiliation and his sufferings in Spain, which caused the young man to withdraw into himself and even to develop resentment for his own royal father, whom Henri blamed for his misfortunes. Unlike Henri, Charles was a toddler when King François was captured and when his two elder brothers had to later become hostages in Spain following the monarch’s release after signing the Treaty of Madrid of 1526. Consequently, Charles stayed in France and, hence, was not traumatized in childhood.

Unlike Henri who preferred unostentatious things, Charles was as extravagant and inclined to lavishness as their father was. While Henri detested their father’s frivolous and extravagant court, Charles reveled in the splendor of the enlightened Valois Renaissance court. Henri was a more serious person than Charles, who was known for his wild antics and manners. King François approved of Charles’ behavior, and Charles was more popular at court than Henri. A rivalry developed between Henri and Charles for their father’s affection and in politics, for the nobles preferred Charles to succeed François. It appears that Charles and Henri did not have a close relationship because of their different characters and because of their rivalry.

Unlike Henri who was a staunch Catholic, Charles was interested in new religious ideas and even had a good relationship with Anne de Pisseleu, Duchess d’Étampes, who was his father’s maîtresse-en-titre. Charles had a flair for drama, his antics eccentric and incredible, at times difficult to imagine. During Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s visit to France in the winter of 1539 to 1540, he jumped out of the bushes near the emperor, calling out to Charles V that he was now a prisoner of war. The emperor remembered that he had imprisoned François I and later exchanged him for his two eldest sons (François and Henri) and mistreated them. Maybe fearing that King François could have acted in the same way, the emperor spurred his horse into a gallop and fled, which caused even Prince Henri to laugh because Henri absolutely loathed the Spaniards.

Charles II d’Orléans was the most handsome among François I’s sons. Yet, Charles was blind in one eye, which was a lingering effect of smallpox. This did not make Charles disabled and did not deprive him of the ability to serve as a general. In every inch his father’s heir, Charles was skilled as a swordsman and positioned himself as a chivalrous knight. To gain military experience and to earn glory, Charles was helping his father in the Habsburg-Valois wars – he succeeded in capturing Luxembourg from the emperor. Young and brash, Charles however quickly went south in order not to allow his brother Henri to win another battle, so Luxembourg was inevitably lost, retaken, and lost again. His rivalry with Henri prompted Charles to act so, but if he had stayed in Luxembourg, everything might have gone differently.

To establish an alliance with the Vatican, King François arranged a marriage to Catherine de’ Medici for Prince Henri. In the winter of 1535, King Henry VIII of England offered a betrothal between his 1-year-old daughter Princess Elizabeth Tudor and the 12-year-old Charles, but on the condition that François I would convince Pope Paul III to acknowledge the English monarch’s marriage to Anne Boleyn as legal and valid. The Catholic monarch of a Catholic kingdom, François was unable and unwilling to do so, so the betrothal between Elizabeth and Charles was not concluded. Most definitely, François was concerned about Elizabeth’s legitimacy. After Anne’s execution, this engagement was never considered again.

At the time, Prince Charles was still young, so his father could let his youngest son remain without a match for some time. King François, who was obsessed with the idea to regain his Milanese inheritance as a direct descendant of Valentine Visconti, participated in several Italian wars. On the 19th of September 1544, the Treaty of Crépy ended the Italian War of 1542-1546 – it was another meaningless peace treaty between François I and Emperor Charles V. According to this document, the emperor relinquished his claim to the Duchy of Burgundy, while the ruler of France renounced his claims for the Kingdom of Naples, as well as Flanders and Artois.

The Treaty of Crépy created new opportunities for Prince Charles. The Duke d’Orléans had the choice to marry either the emperor’s daughter, Infanta Maria of Spain (future wife of Emperor Maximilian II) or his niece Archduchess Anna of Austria (daughter of future Emperor Ferdinand I). In the first case, the bride would obtain as her dowry the Burgundian Netherlands and Franche-Comté. In the second case, the bride would receive the Duchy of Milan. At the same time, King François was to grant the duchies of Bourbon, Châtellerault, and Angoulême to his son in addition to the Duchy of Orléans and the County of Clermont, which Charles had been given in 1540.

Given François I’s passion for Milan, it is possible that François would have preferred for his beloved son to marry Anna of Austria and become Duke of Milan. If François had really thought so (we cannot prove it, but we can speculate), or if it had happened, Charles would have become as powerful and rich as a monarch in France. Indeed, as Duke of Milan and a son-in-law of Emperor Charles V, Charles d’Orléans, who was also a very powerful magnate in France, could have transformed into a dangerous rival to Dauphin Henri of France. The Treaty of Crépy, which was so beneficial for Charles, offended Dauphin Henri, who considered himself Valentine Visconti’s rightful heir as François I’s eldest surviving son as of 1544. Some historians think that the emperor strove to use Charles as an adversary against Henri to cause civil war in France.

Nobody knows how the relationship between Henri and Charles would have developed further if the Duke d’Orléans had become a subject of his elder brother while also being Duke of Milan or the Lord of the Netherlands. Their potential conflict was prevented by the bizarre death of Prince Charles when both brothers were on their way to Boulogne, which was under siege by the English in the autumn of 1545. Charles – always eccentric, impulsive, and at times unreasonable – was too fond of engaging in risky behavior. On the 6th of September 1545, Henri and Charles found the empty houses that had been closed off due to “the plague” or possibly a form of influenza. Charles entered one of these infected houses with the words:

“No son of a King of France ever died of plague.”

Dangerously self-assured of his own invincibility, Charles II d’Orléans made this fatal mistake. Henri and others unwillingly followed him, but they stayed aside. Allegedly, Charles threw himself onto some bed, starting pillow fights, and then, laughing, he even sliced fabric open with his sword. Certainly, Henri did not behave so recklessly. Doesn’t it look like Charles? After all, we remember how Charles jeered at Emperor Charles V telling the mightiest man in Europe that the emperor was France’s captive. It must have been fun for everyone involved, perhaps even for Henri, and it would have been hilarious if it did not turn out to be so sad.

Later that day at dinner with his brother and their father, Charles began feeling unwell. Soon the poor duke was already having dreadful pains, shaking limbs, and bouts of vomiting while being seized by a strong fever. A shocked Dauphin Henri hurried to his brother’s sickroom, but he was stopped from entering there. Prince Charles breathed his last on the 9th of September 1545, and most historians agree that the “plague” killed him. Some said – those who wanted Charles to be Dauphin – that Charles could have been poisoned, but it seems to be unlikely. His own recklessness and impulsiveness killed Prince Charles. King François was utterly devastated by his favorite son’s demise, Dauphin Henri was also heartbroken. Charles is interred next to his father, King François I, and his brother, Dauphin François, at the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

In France’s history, there is no prince or king who had such an unusual, bizarre death. The word “bizarre” might seem inappropriate when it comes to someone’s death, but we cannot deny that Charles could have survived if he had been more serious and better behaved, at least more careful. About a year and a half later, François I himself would die as well, and Henri would succeed him as King Henri II of France, continuing the conflict with Charles V. At the time of his passing in 1545, Charles II d’Orléans possessed the Duchies of Angoulême, Bourbon, and Châtellerault, being the most powerful magnate in the realm after Dauphin Henri, and had he survived, it is highly likely that France would have plunged into internecine fighting between the Valois brothers in addition to historical religious conflicts.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2022 Olivia Longueville