the links to part 1, part 2, and part 3 of the series “A fatal love triangle: King Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, and Jane Seymour

After the arrests of Anne and George Boleyn, and her other alleged paramours, tension was rising in the air, and the royal court froze in anticipation of the appalling outcome for the Boleyns. Few expected that Anne and other prisoners would leave the Tower of London alive.

As of the 5th of May 1536, not only Anne Boleyn, George Boleyn, Henry Norris, and Mark Smeaton were imprisoned in the Tower. Several other men were also there: Sir Richard Page, a gentleman of the Privy Chamber and Vice-Chamberlain in the household of the king’s illegitimate son, Henry FitzRoy; Sir Thomas Wyatt the Elder, a Tudor poet and courtier, who was a great admirer of Anne Boleyn; Sir Francis Weston, a gentleman of the Privy Chamber and one of the Boleyn supporters; Sir William Brereton, a groom of the Privy Chamber to the king.

During her first days in the Tower, Anne was despondent and hysterical, and her ramblings led to the mention of Francis Weston, who, she muttered, could be in love with her. As a result, Weston was arrested as well. Sir William Brereton was apprehended on the same day, but the cause of his arrest is unclear. In Showtime’s “The Tudors”, Brereton is a devout Catholic working as the Pope’s assassin, who confesses to being Anne’s lover, but this is a product of fiction. Page and Wyatt would survive and be released later, while Weston and Brereton would not.

Thomas Cromwell ordered Sir Francis Bryan, who was a courtier and diplomat related to both Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour, to arrive in London for questioning. He was not apprehended and survived his cousin’s downfall untouched. We don’t know why he was summoned to London by the royal chief minister, for whom it might have been a tactical move to secure additional evidence against Anne if such a necessity arose.

Whose testimony was the critical one in condemning Anne to her gruesome end?

Many assume that the testimony of Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford and George Boleyn’s wife, about Anne’s alleged incestuous relationship with her brother delivered the Boleyn siblings into the hands of their foes. However, there is no evidence that Jane wanted be free of her husband George, that their marriage was of a forced nature, and that she loathed her spouse. There is no credible proof that Jane was the principal witness against Anne and George Boleyn.

When some readers and history enthusiasts think about Anne’s tragedy, their sympathies are with Anne and George – the two wronged and unjustly executed people, victims of Jane Boleyn.

The historian Julia Fox creates a sympathetic portrayal of Jane Boleyn. She writes about Jane’s friendship with Anne and claims that Jane helped her have one of King Henry’s mistresses dismissed from court. In Fox’s opinion, Jane never plotted the downfall of the Boleyns.

On the 4th of May 1536, Jane Boleyn sent a message to George. As she could not send him a personal letter and visit him in the Tower, Jane wrote a formal message to Sir William Kingston, the Constable of the Tower, so that he could give it to George. Kingston reported the case to Cromwell. Jane inquired how her husband was fairing and pledged that she would “humbly suit onto the King’s highness” for him. Whether Jane appealed to His Majesty, it unclear.

Julia Fox writes about Jane’s role in the conspiracy against Anne:

“Thus, Jane Rochford found herself dragged into a maelstrom of intrigue, innuendo, and speculation. For when Cromwell sent for her, he already had much of what he needed not only to bring down Anne and her circle but also to make possible Henry’s marriage to Jane Seymour, the woman Henry was positive was his ideal bride. A few more details were all that was required. The questions to Jane would have come thick and fast.

……….

Faced with such relentless, incessant questions, which she had no choice but to answer, Jane would have searched her memory for every tiny incident she could think of. This was not the moment for bravado and anyway the arrests had been so sudden and unexpected that there was no time to separate out what testimony might be damaging, what could be twisted to become so, or what could only be innocuous no matter what the interpretation. By the end of the various sessions, Cromwell had what he wanted.”

Eric Ives has the opposite opinion and writes of Lady Rochford:

“Why Jane Boleyn provided information is another question. We can dismiss out of hand the nonsense that she felt insulted because George was a homosexual, a fiction for which there is not a scintilla of evidence, indeed, quite the reverse Burnet’s suggestion that Jane was motivated by jealousy of Anne’s closeness to her brother could be correct. Alternatively, she could have been influenced by her own family’s long association with the Princess Mary.

Jane did, it is true, send to ask after her husband in the Tower and promised to intercede with the king, apparently to get him a hearing before the council. However we may, if we choose, smell malice, for the message was brought with Henry’s express permission and by Carew and Bryan in his newly turned coat. It is also the case that Lady Rochford’s interests as a widow were carefully looked after by Cromwell.”

Perhaps Fox is right that Cromwell twisted Jane’s words about Anne and George. Maybe Ives is correct, and Jane betrayed George and the Boleyns out of spite and envy. That said, there is still no credible evidence of Jane being Cromwell’s main willing informant.

Sir John Spelman, who was judge of the King’s Bench, in his report named Lady Wingfeilde as one of the key witnesses against the disgraced queen. Lady Bridget Wingfield (née Wiltshire) was a neighbor, close friend, and lady-in-waiting to Anne; she died in January 1534. Supposedly, she posthumously provided incriminating information about the queen’s shameful behavior.

This is an excerpt from John Spelman’s report:

“And all the evidence was of bawdery and lechery, so that there was no such whore in the realm. Note that this matter was disclosed by a woman called Lady Wingfeilde, who had been a servant to the said queen and of the same qualities; and suddenly the said Wingfeilde became sick and a short time before her death showed this matter to one of her…”

As the Lady Wingfeilde had died long before Anne’s arrest, she could not confirm or refute anything. She was conveniently dead, and it was exactly what Cromwell and Anne’s foes needed.

Eric Ives writes of Cromwell’s other informants:

“Three other court ladies – Anne Cobham, ‘my Lady Worcester’ and ‘one maid more’ – were also believed to be sources of information against Anne. John Hussey listed them in a letter to his employer, Lord Lisle. The significance of what Mrs Cobham said we do not know, but the anonymous lady was almost certainly Margery Horsman, who was well known and useful to Hussey, and whose identity he therefore had reason to keep close.”

Lady Elizabeth Somerset, Countess of Worcester, might have been the chief informant against Anne. She was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Anne, often spent time in the queen’s quarters, and was close to her. According to one reliable source, Elizabeth secretly borrowed 100 pounds from Anne, suggesting a certain level of trust between them; she didn’t repay the debt by the time of Anne’s arrest. This friendship lent credibility to the woman’s accusations against the queen.

It seems that Lady Worcester testified against Anne, saying that her mistress had committed adulteries. This might be described in Lancelot de Carle’s poem “A letter containing the criminal charges laid against Queen Anne Boleyn of England.” De Carles recorded an argument between Lady Worcester, and her brother, Sir Anthony Browne: when her brother accused her of behaving or appearing promiscuous, she replied that she was not “the worst sinner in regards to promiscuous behavior”, maneuvering their argument from herself towards the monarch’s wife.

The Countess of Worcester supposedly told her brother:

“But you see a small fault in me, while overlooking a much higher fault that is much more damaging. If you do not believe me, find out from Smeaton. I must not forget to tell you what seems to me to be the worst thing, which that often her brother has carnal knowledge of her in bed”.

Maybe the above-mentioned argument between the countess and her brother was the crucial in destroying the Boleyns.

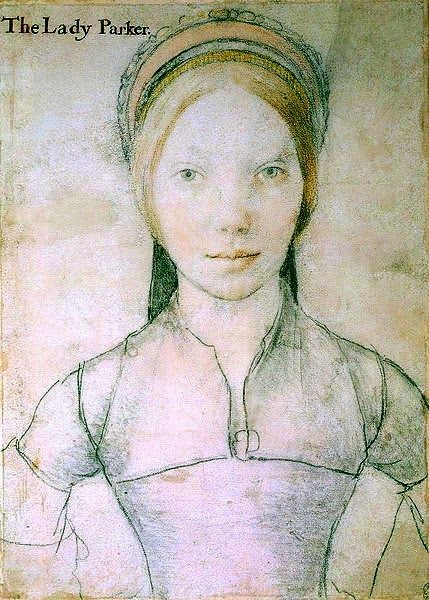

Nothing now remains of Jane Boleyn. We do not know for a certainty how she looked like (there is only one drawing of her, and we cannot be certain that it is Jane’s), where she is buried, and there are few contemporary records about her. At the same time, Jane Boleyn has become a notorious scapegoat for the fall of two of Henry’s queens – Anne and later her young cousin, Katherine Howard. In reality, Jane Boleyn is one of the most thoroughly maligned Tudor women, who is erroneously called a traitor and is unfairly scorned as a scandalous woman. At least in Anne Boleyn’s case, Lady Rochford seems to be simply confused with Lady Worcester.

You can read more in part 5 of this article series ‘A Fatal Love Triangle: Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII, and Jane Seymour.’

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville