On the 22nd or 23rd of July 1536, Henry FitzRoy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset, died at St James’s Palace in London. Although Henry VIII took enough mistresses in his date, he had only one acknowledged illegitimate son – Henry FitzRoy, whose mother was his mistress, Lady Elizabeth Blount. As he had been born on the 15th of June 1519, the duke turned only seventeen over a month before his passing. He died so young… when the whole life could lay ahead of him.

Henry VIII loved his only surviving son and lavished him with titles. In 1525, the little boy of six summers had been given the position of a Knight of the Garter, the most senior order of knighthood in the English honors system at the time. In the same year, he had been gifted with the double dukedom of Richmond and Somerset, and with the earldom of Nottingham. In later years, FitzRoy had been appointed Lord Admiral of England, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord President of the Council of the North, and Chamberlain of Chester and North Wales. FitzRoy had also been given other prestigious positions at court. However, the wheel of fate turned in a tragic direction, and the Duke of Richmond’s brilliant career in politics came to an abrupt end.

Charles Wriothesley, a Tudor chronicler, recorded Henry FitzRoy’s death:

“Also the twentith tow daie of Julie, Henrie, Duke of Somersett and Richmonde, and Earle of Nottingham, and a base sonne of our soveraigne King Henrie the Eight, borne of my Ladie Taylebuse, that tyme called Elizabeth Blunt, departed out of this transitory lief at the Kinges place in Sainct James, within the Kinges Parke at Westminster. It was thought that he was privelie poysoned by the meanes of Queene Anne and her brother Lord Rochford, for he pined inwardlie in his bodie long before he died; only God knoweth the truth therof ; he was a goodlie yong lord, and a toward in many qualities and feates, and was maried to the Duke of Norfolkes daughter named Ladie Marie.”

Most historians concur that Henry FitzRoy died of tuberculosis (consumption). He is also suspected to have died of pneumonic plague that works on its victim in the following way: the infection settles in one’s lungs, and after several days, their lungs become liquefied, while their body is developing pneumonia, chest pain, bad cough, and often bloody sputum. Some contemporary sources describe the public appearances of the king’s bastard son and his activities in the late spring of 1536, including his attendance at the execution of his stepmother, Anne Boleyn. However, that does not mean that FitzRoy was hale and hearty, and his health must have been weakening gradually. If we assume that consumption killed the young man, then he must have fallen ill months before his passing.

The unexpected tragedy caused a stir at the Tudor court. The persistent, yet groundless, rumor that the young duke might have been poisoned circulated. We know that the monarch and his illegitimate son were close, and when Anne had been arrested on the 2nd of May 1536, the monarch was reported to have visited FitzRoy and embraced him, weeping and saying that his son and Mary, Catherine of Aragon’s daughter, were fortunate to escape the fate of being poisoned by Anne. Nevertheless, by the time of FitzRoy’s passing, Anne had been dead for more than two months, and, hence, the idea of her being implicated in his poisoning is totally implausible.

The monarch must have been devastated with the loss of Henry FitzRoy. Years ago, the boy’s birth proved that Henry could sire a healthy son, making it possible for the king to put the blame for the lack of his legitimate male progeny onto Catherine of Aragon. At the time of his son’s death, Henry was already married to Jane Seymour, but she was not pregnant yet, and Prince Edward was not born yet. Thus, the departure of FitzRoy from the world of the living could be perceived by the ruler as the abhorrent stain upon his virility and upon his ability to sire healthy sons. The king’s grief was tinged with painful and selfish hues, being both a personal blow and a political one to Henry VIII.

The extent of the king’s extreme agitation becomes evident in the unconventional arrangements made for the Duke of Richmond’s funeral. The ruler asked his father-in-law – Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk – to have his son buried quietly somewhere away from the English capital. Obeying his sovereign, Norfolk enjoined to have the young man’s body placed in a coffin and then to be surreptitiously transported in a cart out of London. The coffin was placed in a straw-filled wagon, which took the body to Norfolk; his unimpressive train was accompanied only by FitzRoy’s governor and his controller. FitzRoy was interred in the Howard family vault in Thetford Priory, with only the Duke of Norfolk and his eldest son, the Earl of Surrey, in attendance.

Thomas Howard complied with his sovereign’s commands. Nonetheless, King Henry wrote to him several days after FitzRoy’s funeral, rebuking him for not giving his dearly departed son a better funeral befitting the young man’s high station. The monarch seems to have begun to regret his ill-conceived decision, and Norfolk became a convenient scapegoat for him. Henry never blamed himself, always putting the blame onto others or onto something other than the actual cause.

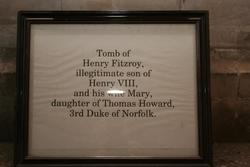

Henry FitzRoy’s tomb at St Michael’s Church, Framlingham

At the king’s behest, Masses were ordered in various churches for the eternal peace of FitzRoy’s soul. Remarkably, only about 80 religious services for the soul of the king’s son would be conducted by April 1537, while a decade later, Henry would consider a far large number of Masses appropriate for his own soul. The construction of the suitable tomb for the Duke of Richmond was left entirely to the Duke of Norfolk and his coffers. Even at first glance, the selfishness of the monarch’s behavior is apparent: Henry resolved not to occupy himself with the death of his son in order to avoid reminding himself, his courtiers, and the world of the lack of his male progeny.

The remains of Henry FitzRoy were later moved to St Michael’s Church in Framlingham due to the dissolution of the priory. His widow, Mary Howard, would be buried together with him in 1557.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2019 Olivia Longueville