On the 7th of September 1533, Anne Boleyn birthed a daughter – the future Queen Elizabeth I of England. It happened at Greenwich Palace, where Queen Elizabeth of York had given birth to King Henry VIII. At first, Anne’s pregnancy had been without any complications, and the proud mother coped with a long coronation procession and exhausting pageants at the beginning of June 1536 when she was about 6 months along in her pregnancy. It nevertheless appears that at the late stages of her pregnancy, Anne had felt unwell and tired easily, so there had been no royal progress that summer, which Henry and Anne had spent at Windsor Castle.

Upon the monarch’s orders, a special chamber for Anne’s confinement had been prepared at Greenwich Palace at the end of August. The court had moved to Greenwich, and on the 26th of August 1533, after a Mass at the Chapel Royal, Anne had entered her confinement. Another procession formed as the courtiers and the king accompanied Anne to the door of her bedchamber, where they parted ways according to the traditions of the time. Anne entered together with her ladies-in-waiting and lived only in a female world, attended solely by women until the birth of her baby and her churching 30 days after. Such ceremonies emphasized in the eyes of a medieval and Renaissance person that childbirth was an exclusively female business.

The British historian David Starkey describes in his biography about Elizabeth I:

“The walls and ceilings were close hung and tented with arras – that is, precious tapestry woven with gold or silver threads – and the floor thickly laid with rich carpets. The arras was left loose at a single window, so that the Queen could order a little light and air to be admitted, though this was generally felt inadvisable. Precautions were taken, too, about the design of the hangings. Figurative tapestry, with human or animal images was ruled out. The fear was that it could trigger fantasies in the Queen’s mind which might lead to the child being deformed. Instead, simple, repetitive patterns were preferred. The Queen’s richly hung and canopied bed was to match or be en suite with the hangings, as was the pallet or day-bed which stood at its foot. And it was on the pallet, almost certainly that the birth took place. At the last minute, gold and silver plate had been brought from the Jewel House. There were cups and bowls to stand on the cupboard and crucifixes, candlesticks and images for the altar.”

Henry and Anne had been assured by astrologers that she carried a son. However, their predictions were wrong: at 3 o’ clock in the afternoon, on the 7th of September 1533, the bonny red-haired baby girl emerged from Anne’s womb. There was no Salic law in England preventing females from inheriting the throne, but female ascension was undesirable. Everyone, including Henry, remembered how Empress Mathilda, the only surviving legitimate child of Henri I of England, and her husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, had fought against King Stephen of England during the Anarchy. The civil war had devastated the country for years and ended with Stephen’s consent to make Mathilda and Geoffrey’s eldest son – Henry Plantagenet, the future Henry II of England – his heir. Henry VIII was afraid of allowing any of his daughters to succeed him, so the birth of Elizabeth crushed his hopes for a boy into smithereens.

The jousts that had been planned to honor the birth of his son were all cancelled. The baby girl’s birth – a princess of doubtful legitimacy in the eyes of many – did not need to be celebrated in public. King Henry, who had moved heaven and earth to marry Anne, must have been extremely furious and disappointed in his second wife. The royal heralds announced the birth of Henry’s first legitimate child – such an amorphous promulgation! The choristers of the Chapel Royal sang The Te Deum in accordance with tradition, and bonfires were lit throughout the country with little enthusiasm. The people, most of whom were Catholics and supported Catherine of Aragon, did not love Anne Boleyn, considering her a homewrecker, a wanton woman, and a usurper.

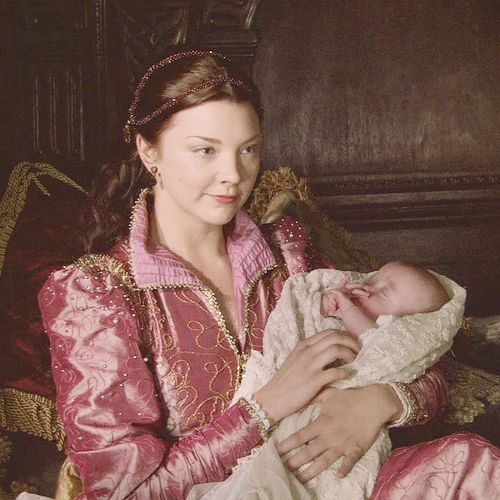

Elizabeth nonetheless received a splendid christening ceremony when she was only 3 days old. It took place on the 10th of September 1533 at the Church of Observant Friars at Greenwich. Anne remained confined to her apartments until her churching. Elizabeth’s godfather was Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was one of the few people who genuinely loved Anne Boleyn and would later regret her death. Her godparents also included: Agnes Howard née Tylney, Dowager Duchess of Norfolk; Margaret Grey née Wotton, Marchioness of Dorset; and Gertrude Courtenay née Blount, Marchioness of Exeter. I am certain that Anne loved her daughter dearly, but from that moment onwards, Henry’s passionate feelings for her started cooling.

Anne had conceived Bess quickly after having her first intercourse with Henry, presumably during their meeting with King François I of France in Calais in October 1532 or very soon after their return to England. Anne could also be with child in 1534. In one of his letters to Emperor Charles V (dated the 28th of January 1534), the Imperial ambassador Eustace Chapuys mentioned that Anne was pregnant. George Taylor, who was in Anne’s employ for a few years before her coronation, informed Lady Lisle about the queen’s condition on the 7th of April 1534:

“The Queen hath a goodly belly, praying our Lord to send us a prince.”

In July 1534, George Boleyn went to France to ask for a postponement of another meeting between Henry VIII and François I. It means that Anne was most likely pregnant in the first half of 1534, and yet no healthy child was born. However, the baby could not vanish into thin air! She probably miscarried her second baby she conceived shortly after Elizabeth’s birth. Anne might have conceived in 1535, but there is no proof of this, save a sentence from William Kingston’s letter to Lord Lisle on the 24th of June 1535 when Kingston wrote:

“Her Grace has as fair a belly as I have ever seen.”

There is no other information about the result of this pregnancy, and we do not know whether it is true. Maybe there was an error in dating this letter, or Anne could have expected another baby again, but in this case, she lost it. Anne was definitely pregnant in 1536. On the 24th of January 1536, Henry was unhorsed during a tournament, and on the 29th of January 1536, shortly after the jousting accident, she suffered another miscarriage of a male fetus of several months in gestation. Eustace Chapuys, a devout Catholic and Catherine’s staunch supporter, wrote that Henry, during his visit to the queen’s bedchamber after the tragedy, said very little except for:

“I see that God will not give me male children.”

Following the disaster, King Henry was distant from Anne, growing more enamored of Jane Seymour. He left Anne at Greenwich to convalesce and went to the Whitehall Palace to mark the Feast of St Matthew. Anne’s enemies claimed that she miscarried “shapeless mass of flesh”, which could lead the monarch to believe that God had cursed his second marriage. Was it really a deformed male child? The only source suggesting that it was so was Nicholas Sander, a Catholic recusant writing during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I; he was hell-bent on slandering the long dead woman and is untrustworthy. Therefore, Anne had at least 2 or perhaps 3 pregnancies.

Alison Weir writes about the reasons for Anne’s misfortunes:

“The real reason for the miscarriages may have been that Anne was one of the small minority of people who are rhesus negative and who, during a first pregnancy which results in a healthy child, may produce in the bloodstream a substance called agglutinogen, which destroys rhesus-positive red cells in any subsequent fetus, usually with fatal results. Such a condition was of course unknown in the sixteenth century – it was not identified until 1940.”

Catherine of Aragon was married to King Henry for years before he commenced questioning the validity of his union with her. She had at least 6 pregnancies, but historians have always speculated on the number. Hester Chapman believes that Catherine was with child 7 times; Pollard brings the number up to 10, which seems doubtful. Opinions of historians differ, but we know that Catherine’s marriage to Henry produced one surviving daughter, Mary Tudor, while all of their other children were stillborn or died shortly after birth or were miscarried.

In Anne’s case, we have evidence only for 3 pregnancies: the first one resulted in Elizabeth’s birth and 2 ended with miscarriages. In 1536, Chapuys wrote to his master (a letter dated the 10th of February 1536) that Anne miscarried on the day of Catherine’s funeral, meaning that the tragedy happened on the 29th of January 1536. Jane Seymour birthed Henry’s long-awaited male heir – the future King Edward VI, but she died soon after the labor, so we do not know whether she would have suffered numerous miscarriages just as Catherine and Anne did.

Some researchers think that a rare blood disorder could be the reason why King Henry had only few surviving children by his 6 wives. Henry could have been ‘Kell positive’, which is a rare blood type that might cause fertility problems. If he was ‘Kell positive’ while his wives were ‘Kell negative’, then each of his conceived babies had a 50-50 chance of inheriting the condition. If a baby is also ‘Kell negative’, a mother is likely to have complications during all future pregnancies because the antibodies she produces during her first pregnancy will attack future ‘Kell positive’ babies in her womb, triggering miscarriages. If Henry suffered from type II diabetes, this could explain the fertility problems of his queens, particularly Catherine’s, for diabetes results in low sperm count and erectile dysfunction. It might also explain the lack of pregnancies in his marriages after Jane Seymour. Another possibility is that Catherine and Anne might have been victims of the time because there was not much known about prenatal care back then.

There are other theories explaining Henry’s reproductive problems. Some say that Henry could have had syphilis that could explain his ill health, as well as his wives’ repeated miscarriages. In the Middle Ages, syphilis was treated with mercury, but there are no records that Henry received treatment of this kind. Moreover, he had 3 healthy legitimate children and at least one illegitimate child – Henry Fitzroy. The treatment of syphilis with mercury originated in the early 1530s when the physician Paracelsus first prescribed it. Thus, if Henry had become infected with this venereal affliction before he married Catherine in 1509, his syphilis could have reached its latent stage by the time Paracelsus first used mercury. Yet, this theory cannot be confirmed.

Perhaps Anne was Rhesus negative (Rh-), so her body rejected all Rhesus positive babies after the first pregnancy, causing further miscarriages. Thus, she successfully gave birth only to Elizabeth and lost all of her other children, assuming that Henry was Rhesus positive. However, we have to wonder why Catherine suffered even more miscarriages than her younger rival. Anne was under more stress: she knew that she did not have as many years as Catherine had to produce a male heir. It is difficult to imagine the horrible anxiety Anne felt knowing that she had to deliver a son urgently, so stress could have triggered her miscarriages. This nevertheless does not explain why Catherine’s tragic childbearing history exhibited the same patterns as Anne’s did.

I think King Henry had a rare blood disorder. The detrimental effects of inbreeding must have had a significant impact on Henry’s health and his reproductive ability. Henry’s parents were cousins: Elizabeth of York and Henry VII both descended from John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, who was a son of King Edward III of England and his consort, Philippa of Hainault. This makes his parents 3rd cousins! The Beaufort line was also inbred if we look at their ancestry tree. Henry VIII was rather closely related to 2 of his wives: Catherine of Aragon and his last spouse, Catherine Parr, for the 3 of them shared common ancestry starting from John of Gaunt. Anne Boleyn descended from Edward I of England and his daughter Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, yet while King Henry VIII also descended from Edward I, Anne and Henry were not very closely related.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville