A great Renaissance French poet, Clément Marot was born at Cahors, the capital of the province of Quercy, on the 23rd of November 1496. His father, Jean Marot, was also a poet and served as escripvain (a poet-historian) to Anne de Bretagne, Queen of France. Although in his youth Clément studied law at the University of Paris, he was more inclined to the arts and poetry in particular. Jean Marot educated his son and taught him how to compose in the fashionable forms of verse-making.

Clément began his career as one of les grands rhétoriqueurs – poets working from 1460 to 1520 in Northern France, Flanders, and Burgundy. They combined stilted and whimsical language with allegories of the 15th century and artificial forms of the ballade and the rondeau. Clément found their poems rather ostentatious despite their extremely rich rhyme scheme and experimentation with assonance and puns. Nevertheless, Clément departed from what he considered an old-fashioned style.

After abandoning his studies, Clément entered into the service of Nicolas III de Neufville, Seigneur de Villeroy, who was a secretary to the Valois royal family. As Villeroy admired the young poet’s talent, he introduced Clément to his art-loving sovereign – King François I of France and then to his remarkable sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême (later Queen Marguerite of Navarre). François and Marguerite had a great passion for books and were devoted to literature. Thus, Clément Marot was attached to Marguerite’s household and became a member of her inner literary circle. The artist also gained François I’s high favor, with whom he became friends. Marot attended the magnificent Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, and he elegantly celebrated it in many verses.

His close friendship with King François led Clément Marot to accompany the monarch to Italy in 1524. After the disastrous defeat of the French troops at Pavia, François was taken prisoner by the Imperial forces, but there is no information about Clément’s injuries. Clément, who didn’t participate in the battle, escaped and returned to Paris at the beginning of 1525. However, the situation in the political circles of France was changing in the king’s absence, so the conservative Catholics took steps to restrict the spreading of what they called heresy. Marot, whose interests in new religious ideas were widely known, was arrested on a charge of heresy and jailed in the Grand Châtelet in February 1526. A prelate, acting on behalf of Marguerite, soon arranged his release.

When King François came back from Spain, Clément Marot was already a free man. François made him the official poet at his court to keep him close. Although Clément had a warm relationship with the monarch, he worshipped the king’s sister – Marguerite, whose beauty, grace, literary talents, and intelligence he hailed as God’s gifts. There is no evidence of anything romantic between them as Margot seems to have been in love with her second husband – Henri d’Albert, King of Navarre. Clément wrote poems for Marguerite, and some scholars think that he could have developed unrequired feelings for his patroness, expressed in his poem ‘De celui, qui est demeuré, et s’amie s’en est allée’, or in English ‘Of him, who remained, and his friend is gone’, where he bares his heart.

All on his own, he is melancholy

Your servant, who is from your place,

Where we want to sing, dance and laugh:

Alone in his room he pens his sorrow,

There is nothing better for him to do.

Because when it rains, and the sun in heaven

Fails to shine, all men are anxious,

Every creature retreats to its den,

All on its own, retreating away.

Now tears are raining from my eyes,

And you, who are my gracious sun,

Abandon me to torment’s shadow:

And so I conceal myself from all,

Lest my pain prove pain to them,

All on its own.

Who was the sun of Marot’s life who despite her grace abandoned him to torment’s shadow? Perhaps the artist indeed thought of Marguerite de Valois when he composed this majestic verse. While it is written in an elegiac style, it sounds amazing, especially in French.

Tout à part soi est mélancolieux

Le tien servant, qui s’éloigne des lieux,

Là où l’on veut chanter, danser et rire :

Seul en sa chambre il va ses pleurs écrire,

Et n’est possible à lui de faire mieux.

Car quand il pleut, et le Soleil des Cieux

Ne reluit point, tout homme est soucieux,

Et toute bête en son creux se retire

Tout à part soi.

Or maintenant pleut larmes de mes yeux,

Et toi, qui es mon Soleil gracieux,

M’as délaissé en l’ombre de martyre :

Pour ces raisons, loin des autres me tire,

Que mon ennui ne leur soit ennuyeux

Tout à part soi.

In 1532, Clément published the printed collection of his works under the title of Adolescence Clémentine. His poems were extremely popular and often reprinted with additions, and the Valois siblings adored them. Unfortunately, trouble was brewing again: Marot’s enemies ensured that the artist was implicated in the 1534 Affair of the Placards, when anti-Catholic posters were discovered in public places in Paris, Blois, Rouen, Tours, and Orléans. The worst was that one of them was left on the bedchamber door of King François at Amboise, which enraged the monarch immensely. The king advocated religious tolerance, but the poster on his door caused him to consider it a threat to his own safety, and it was one of the few times when François persecuted Protestants.

Despite his privileged status at the Valois court, Clément Marot ran away from France. At first, he stayed at the court of King Henri II of Navarre and his wife, Marguerite, in Nierac. Later, he traveled to Ferrara, protected by Princess Renée de France, King Louis XII’s daughter and Duchess of Ferrara. Yet, Renée’s husband was against the presence of the French at his court, and he was also an ardent Catholic, so Marot had to leave. While in exile in Italy, Marot wrote his famous ‘Epistre au Roy, du temps de son exil à Ferrare’, or his Epistle to the French monarch, in which the artist defended his views and accused his persecutors, including François himself. In the end, the artist abjured Protestantism in 1536 and was again appointed by King François his favorite court poet.

Clément Marot’s non-religious verses were composed in an amusing and entertaining style. His poems were written in such a light-hearted manner that it caused the audience to smile. He must have been such a great fun to be around at the French Renaissance court, and no wonder that both François and Marguerite adored Marot and his poetical output. For example, let’s take a poem ‘Changeons propos, c’est trop chanté d’amours’, which in English means ‘Let’s change the subject, that’s enough singing of love’. What an eye-catching beginning to such a marvelous poem!

Changeons propos, c’est trop chanté d’amours,

Ce sont clamours, chantons de la serpette:

Tous vignerons ont à elle recours,

C’est leur secours pour tailler la vignette;

Ô serpillette, ô la serpillonnette,

La vignollette est par toy mise sus,

Dont les bons vins tous les ans sont yssus!

Le dieu Vulcain, forgeron des haultz dieux,

Forgea aux cieulx la serpe bien taillante,

De fin acier trempé en bon vin vieulx,

Pour tailler mieulx et estre plus vaillante.

Bacchus la vante, et dit qu’elle est seante

Et convenante à Noé le bon hom

Pour en tailler la vigne en la saison.

Bacchus alors chappeau de treille avoit,

Et arrivoit pour benistre la vigne;

Avec flascons Silenus le suyvoit,

Lequel beuvoit aussi droict qu’une ligne;

Puis il trepigne, et se faict une bigne;

Comme une guigne estoit rouge son nez;

Beaucoup de gens de sa race sont nez.

We can also translate this poem into English, although in French in sounds better to my ears:

Let’s change the subject, that’s enough singing of love.

It’s empty noise, let’s sing of the pruning-knife.

All wine-growers make use of it;

they need it for cutting their vines.

Oh tiny knife, oh cute little cutter,

with your help they trim and train the young plants

which produce good wines every year.

The god Vulcan, the blacksmith of Olympus,

wrought in heaven that good keen blade

out of fine steel soaked in good old wine

to make it sharper and more valiant.

Bacchus praised it, declaring it a fit

and ideal tool for good father Noah

to use in the vine-pruning season.

At that time Bacchus wore a vine-leaf hat

and used to come to bless the vines.

Bearing flagons Silenus followed –

he used to drink standing straight as a die,

and then stagger about and bump his head.

He had a nose as red as a cherry

and many folk are his descendants.

Soon Clément’s famed Psalms appeared. They were sung at the French court under the music of the illustrious French Renaissance composers Claude de Sermisy and Clément Janequin. Despite the fact that these Psalms did a lot to promote Calvinism ideas, François enjoyed them. Although the Psalms were published in 1541 and 1543 with royal permission, Marot was too often accused of heresy without official charges. In spite of remaining in royal favor, Clément remembered his exile in Italy and, fearing to be arrested because of heresy again, he fled to Geneva in 1543, where he met with John Calvin and continued working on the Psalms. Then Marot traveled to Turin, where he died of unknown causes on the 12th of September 1544 and was interred in the Turin Cathedral at the expense of the French ambassador to Rome. According to some sources, King François was confused because he did not plan to have Marot apprehended and genuinely mourned for his death.

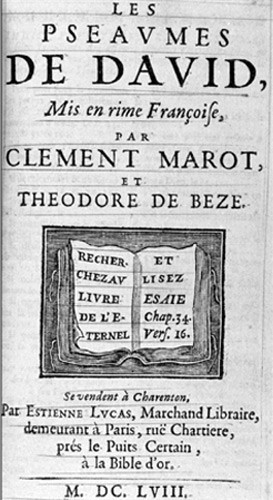

Clément Marot’s works had a serious impact on the Protestant Reformation in France. By 1544, he had versified 49 Psalms, and after Marot’s death, Calvin tasked Theodore de Bèze (a French Reformed Protestant theologian) to continue the artist’s work and complete the versification of the 150 Psalms of the Bible. Marot’s poetical transpositions of the biblical Psalms were adopted by the emerging Reformed Churches and provided with melodies to serve in liturgy. The translations of the Psalms were sung by the French Huguenots during the Wars of Religion in France after the demise of King Henri II in 1559. They were also performed by other Protestant congregations for centuries.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville