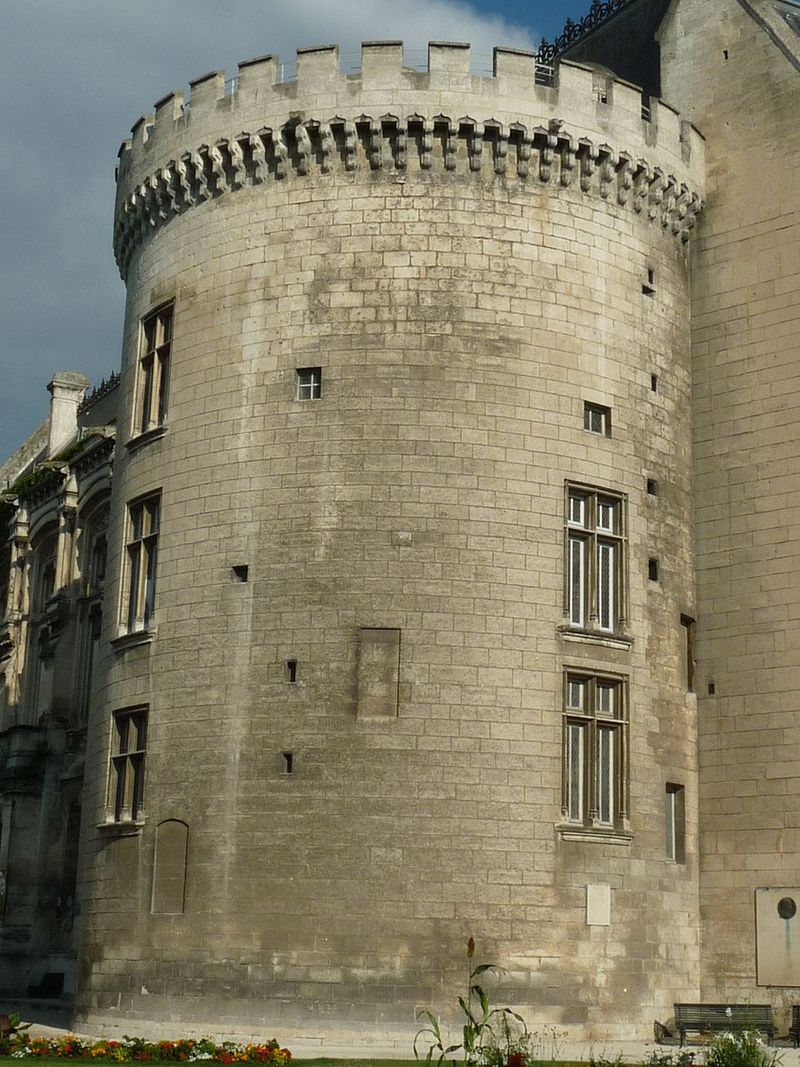

Marguerite d’Angoulême, the daughter of Count Charles d’Angoulême and his wife, Louise de Savoy, was born on the 11th of April 1492 at Château de Cognac in the county of Angoulême. This illustrious Renaissance queen, for she eventually married Henri d’Albert, King of Navarre, deserves to be remembered, while her great contribution to the creation of the French Renaissance cannot be underestimated. She died at Odos, France, on the 21st of December 1549 at the age of 57, having outlived her beloved brother, King François I of France, by only 2 years.

Marguerite had two husbands. Her first spouse was Charles de Valois, Duke d’Alençon, who died in 1525 and with whom she did not have any children. She then married King Henri II of Navarre, with whom she had one surviving daughter – Jeanne d’Albert, or Jeanne III of Navarre. Did Marguerite had other prospects of marriage in her adolescence? Did she dream to marry someone else in her early youth? Did she have any betrothals? The answer is yes to these questions. This article’s goal is not to write about Marguerite’s entire life, but to give her tribute on another anniversary of her death by focusing on her youthful romances and betrothals.

In the spring of 1503, soon after the death of Prince Arthur Tudor, the matter of Marguerite’s possible marriage to the new Prince of Wales was discussed. Marguerite was 11 years old, so she was approaching a marriageable age, and it was normal back then to arrange unions for offspring of royals and nobles so early in their lives. King Louis XII of France dispatched Jacques II, Count de Montbel d’Entremont, to England with the official proposal of Marguerite’s marriage to young Prince Harry who was only a year older than Marguerite. King Henry VII of England, who did not wish to offend his French counterpart, would probably have accepted the proposal had Marguerite been the king’s daughter, but the girl was a Valois prince of the blood’s daughter.

Courteously, Henry VII rejected this proposal. The English ruler was considering the idea of marrying his son, Prince Henry, to Catherine of Aragon, Arthur’s widow, in order to retain the wealthy dowry in money and jewels, which Catherine had brought with her from her home country. Perhaps years later, King Henry VIII of England would come to regret his marriage to Catherine who would fail to give him a male heir, but only until he would meet Anne Boleyn. Having returned from England with nothing, the Count de Montbel d’Entremont met with Louis XII who was on his way to Italy at the time, and Louis was rather displeased with the answer, for although he was still relatively young and could have more children, he loved Marguerite dearly.

Cardinal Georges d’Amboise, France’s chief minister, wrote:

“He [Louis XII] loved Marguerite as his own child.”

Young Marguerite was a girl at the cusp of puberty. She was not beautiful, although she was said to have been born smiling due to the sweetness of her demeanor, her style and elegance, her refined manners, and her grace. The princess was very notable for her aptitude to learning, and her astounding precocity surprised her tutors, making her mother, Louise, very proud of her. Margot’s progress in studies was extraordinary: she was well versed in traditional female things, which were boring for her, and she had a talent in languages – she spoke Italian, Spanish, and Latin languages, as well as a little Greek and German. Her accomplishments in theology, philosophy, and humanism under the tuition of Robert Hurault, Abbot of Saint-Martin d’Autun, were impressive.

Pierre de Bourdeille, Seigneur de Brantôme (a French historian, soldier, and biographer) was born when Marguerite was nearing her fifties, but he wrote about her childhood in his works:

“She [Marguerite] was a princess of enlarged mind, being very able both as to her natural and acquired endowments.”

Pierre de Rohan, Marshal de Gié, was a contemporary of Louise de Savoy and Louis XII of France, the monarch’s trusted councilor. De Gié spoke about young Marguerite :

“bien sage de son âge.”

or:

“Very wise for her age.”

Noel Williams, author of ‘The Pearl of Princesses: the life of Marguerite d’Angoulême, Queen of Navarre,’ wrote about Marguerite’s appearance:

“Beautiful she [Marguerite] was not, despite all that the poets have written about her; but she possessed, nevertheless, sufficient attractions to command numerous admirers, and, in one instance at least, as we shall presently see, to inspire a most violent passion. She was tall and slender, and very graceful in her carriage and all her movements. Her hair, which was very abundant and of a lightish brown color, is concealed in the only authentic portraits which we possess of her under a close-fitting black coif a fashion which imparts a certain severity to her countenance. Her eyes were of a violet hue and remarkably expressive; her eyebrows slightly arched, like her mother’s; her forehead broad and straight, and she had the long nose which both she and her brother, François, had inherited from Charles d’Angoulême, and which she was to bequeath to her daughter, Jeanne d’Albret, and Jeanne, in her turn, to Henri IV.”

The most unpleasant surprise awaited Marguerite in 1505-6 when the recently widowed King Henry VII of England wished to wed her. At first, the English ambassador offered his liege lord’s hand in marriage to Louise de Savoy, who steadfastly rejected the proposal under the pretext that she could not have forsaken her children in France. Nevertheless, when the diplomat asked for her daughter’s hand, Louise did not object disregarding the bridegroom’s age, for Henry VIII could have been a grandfather of the 13/14-year-old Marguerite. Anne de Bretagne (Anne of Brittany) and Louis XII approved of this union, for Marguerite would be Queen of England, and in the opinion of the people of the time, that ought to compensate her for everything.

Sir Richard Herbert, the English ambassador to France, traveled back to England with a diplomatic note from Louis XII, in which the Valois ruler pledged to treat Marguerite as his own flesh and blood, and to provide her with dowry befitting a monarch’s daughter. Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester, who arrived in France as a new Tudor ambassador, responded that his practical sovereign yearned to know the size of the dowry which he would receive, taunting Louis with the news (true or not) that he had received from Spain an offer of a princess with a huge dowry. Louis offered 175,000 livres and a sumptuous trousseau, and his Tudor counterpart accepted.

Marguerite was then informed about it. King Louis and Louise, her mother, anticipated her to obey them, but the girl did not. Marguerite already developed independence in her character, and with her education based on Renaissance humanism, she was a representative of the new era. She wished to live in her home country, expecting her brother to ascend to the French throne and then to be able to live in a new, enlightened France, which she and François dreamed to create. Marguerite shed lakes of tears in front of Louis and her mother, rejecting the opportunity to marry the aging Henry VII, while François entreated them not to send his sister away to England.

Marguerite got what she wished: her marriage to Henry VII did not proceed. However, she achieved a marriageable age and had admirers. Thanks to her mother, she was already surrounded by intellectuals – such people who would be part of her entourage for the rest of her life. Despite being young, she was already a practiced coquette in a decorous way, learning the art of bewitching men not with her looks, but with her intelligence, benevolence, and elegance. Her head full of Italian and medieval romances, Marguerite dreamed of eternal love with a charming nobleman, and she set her eyes on Gaston de Foix, Duke de Nemours, who was the maternal nephew of Louis XII. Gaston was only 3 years older than her, which was an ideal option for her.

The story of her youthful romances is described in Marguerite’s 10th nouvelle of her work ‘The Heptaméron,’ in which she masked her identity with the name Florida. Two young princes, friends of her brother, were among the princess’ admirers. One of them was the Duc de Cordone, who seems to have been Marguerite’s first husband – Charles d’Alençon. This man found little favor with Florida despite his awkward efforts to charm her. At the same time, the other admirer, called the Infant fortune, awakened tender sentiments in the princess’ heart. Doubtless the Infant fortuné was the courageous and chivalrous Gaston de Foix, who often came to Château de Cognac or Château de Amboise, where the princess was raised.

One of Florida’s maids-of-honor in the Nouvelle says:

“We shall have the handsomest couple in Christendom. . . . He [Gaston de Foix] is one of the handsomest and most perfect young princes in existence.”

Gaston de Foix appears to have been quite attracted to young Marguerite d’Angoulême. Yet, over time, his visits to Cognac became less and less frequent, and they did not have the chance to see each other regularly. Perhaps Gaston and Marguerite maintained some secret correspondence, but if it is so, Louise de Savoy must have stopped her daughter. Soon Gaston’s affections shifted to another young woman, while someone who is called in ‘The Heptaméron’ Amadour entered the stage and became Marguerite’s new admirer. Amadour can be identified as Guillaume Gouffier, Seigneur de Bonnivet, who was brought up together with François as his companion. We don’t know whether Marguerite had any amorous sentiments towards Bonnivet, but in her writings, she stated that Florida liked the attention of Amadour despite missing the Infant fortuné.

As Marguerite grew up, it became impossible for her to repudiate another proposal, this time to Charles, Duke d’Alençon, who was descended from the youngest brother of King Philippe VI of France and was a handsome, but incompatible with her man. King Louis XII, Queen Anne de Bretagne, and Louise de Savoy organized everything; Marguerite was not consulted on the matter. The marriage contract was signed at Château de Blois in October 1509, and the wedding ceremony was conducted on the same evening. Splendid festivities followed. Marguerite’s dowry amounted to 60,000 livres, in addition to the county of Armagnac, which Louis ceded to her. The princess, now Duchess d’Alençon, was not happy, perhaps remembering her other admirers.

Did Marguerite think about Gaston de Foix, Duke de Nemours, after her marriage? Perhaps she did, but we do not know about it for a certainty. According to some historical sources, Gaston was the only true love of Marguerite, but I perceive her feelings for him as her youthful crush on the attractive, charismatic, and chivalrous man. Gaston de Foix was in charge of all the French armies in Italy in 1512. During his short, yet brilliant, military career, Gaston demonstrated that he was an outstanding commander of the Renaissance, one who was well ahead of his time. His heroic and unfortunate death at the Battle of Ravenna in April 1512 brought much grief to Louis XII and Marguerite, who is reported by some sources to have wept in the privacy of her rooms.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2021 Olivia Longueville