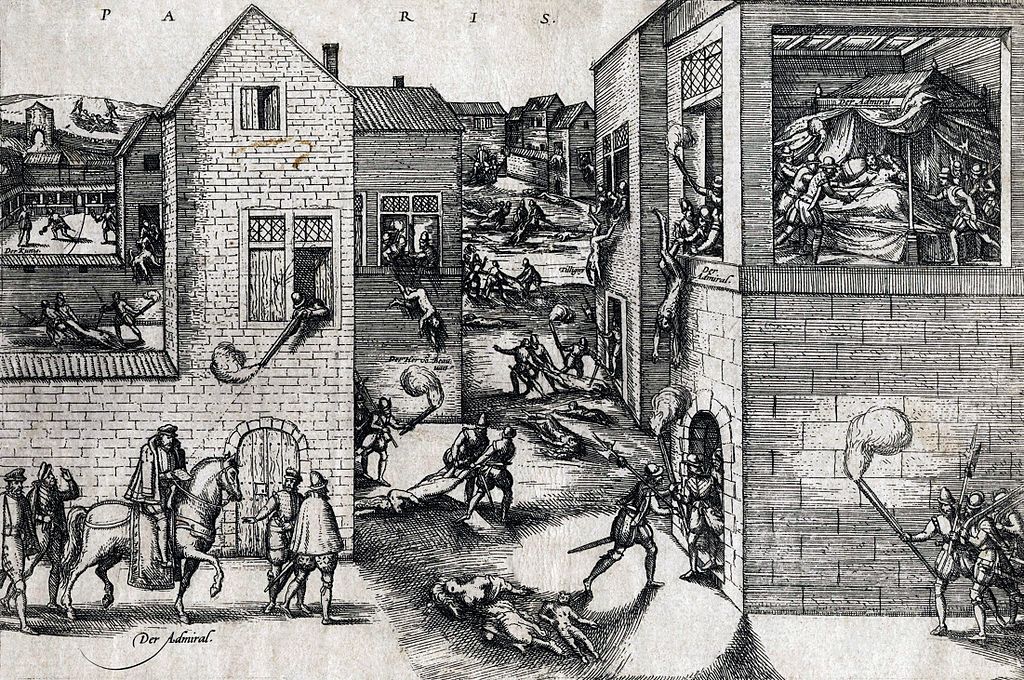

On the night of the 23 and 24th of August 1572, the sanguineous St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was carried out in Paris. It was the cold-blooded murder of thousands of French Protestants called ‘Huguenots’, which appears to have been orchestrated by the formidable mother of King Charles IX of France – Catherine de’ Medici. As Catherine was a dominant figure in the Valois family, it is difficult to imagine that Charles commanded to kill all those Huguenots on his own.

After years of trying to find a consensus with the Huguenot faction, Catherine no longer saw any opportunity to establish the religious balance in the country, so she allowed the House of Guise and her son’s radical politicians to preside over the feast of Protestant bloodshed. Their intent was to strike at the heart of Huguenot nobility, many of whom had arrived in the capital of France for the marriage of King Henri III of Navarre and her daughter, Princess Marguerite de Valois. It was very convenient for the Guise faction, which had merged with the Valois interests by this time, to implement their plans as the leaders of the opposing faction were all present in the same city.

During the week prior to the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, political and religious tensions had already been running intensely high. Two days before the bloodbath, an attempt on the life of Gaspard de Coligny, Seigneur de Châtillon and Admiral of France, had been made, but it had failed – Coligny survived. Admiral de Coligny had been shot in the street by someone called Maurevert from a house owned by Duke Henri de Guise, who presumably had once had an affair with Margot. We don’t know for a certainty who had hired Maurevert to kill Coligny, but there are 3 possibilities: the members of the House of Guise, Catherine de’ Medici, or the Duke of Alba on behalf of King Philip II of Spain. The latter seems to be the least probable candidate for this role. However, King Charles had sent his own physician to tend to Coligny’s wounds, whereas the Queen Mother had pledged to investigate the situation in order to placate the Huguenots’ rage, while in reality it had been done to lull their vigilance. Catherine had secretly met with a group of nobles at Tuileries Palace, where the plot of the annihilation of the non-Catholics who were in the city had been devised.

On the night of the 23rd of August, the members of the Parisian municipality were all summoned to Château de Louvre and given their orders. In the early-morning hours of the 24th of August, on the eve of the Feast of St. Bartholomew, just 6 days after the mixed-faith wedding that had been supposed to heal the religious rift, the Catholics and a lot of soldiers marched into Protestant neighborhoods, shouting “Kill them all!” The bell of the Church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, located close to Château de Louvre, commenced to toll like a mourning dirge, and the massacre began. The first victim was Admiral Gaspard de Coligny: the guards pulled him from his sickbed and stabbed him with axes, then threw his corpse out the window into the courtyard below. Coligny’s head was severed and taken to the Louvre to prove the fact of his demise.

The killings did not stop there, and the bloody Bacchanalia rushed through the city like a flood of lethal poison. The royal soldiers and those who served the House of Guise went everywhere – in every house and mansion in Paris – where they suspected the Huguenots could be staying or hiding. Those inhabitants of Paris who were Catholics soon joined the soldiers in their bloody mission, and the monsters of bloodlust were gripping them more tightly as more and more shocked Huguenots, who had not anticipated such a brutal attack on them, fell dead in their homes and in the streets. The beautiful Paris represented the worst scenes of carnage that could perhaps have been seen in the East during the era of the Crusades as the Christians and the Muslims butchered each other.

The Huguenot blood flowed like torrents of deadly rain, its pungent scent permeating the air. The successful killings unleashed an unprecedented explosion of visceral hatred against all of the Protestants throughout the city. Chains were used to block streets so as to preclude the victims from escaping from their houses. The slaughter was merciless and lasted for 3 days. The dead received no decent burial: their bodies were collected in wagons and thrown into the Seine. Two Huguenot princes of the blood – King Henri of Navarre, Marguerite’s husband, and his cousin – Henri, Prince de Condé – were spared and pledged to convert to Catholicism.

Marguerite de Valois rescued several prominent Protestants during the massacre by keeping them in her rooms, including her spouse Henri, whose name was on the list of the proscribed, bravely refusing to admit the assassins inside. That must have been a shock for Catherine to later discover Henri alive! Margot’s eye-witness account of the massacre in her Memoirs is the only one from the royal family. In the epistolary form in her Memoirs, Marguerite wrote:

“… every hand was at work; chains were drawn across the streets, the alarm-bells were sounded, and every man repaired to his post, according to the orders he had received, whether it was to attack the Admiral’s quarters, or those of the other Huguenots. M. de Guise hastened to the Admiral’s, and Besme, a gentleman in the service of the former, a German by birth, forced into his chamber, and having slain him with a dagger, threw his body out of a window to his master.

I was perfectly ignorant of what was going forward. I observed everyone to be in motion: the Huguenots, driven to despair by the attack upon the Admiral’s life, and the Guises, fearing they should not have justice done them, whispering all they met in the ear.

The Huguenots were suspicious of me because I was a Catholic, and the Catholics because I was married to the King of Navarre, who was a Huguenot. This being the case, no one spoke a syllable of the matter to me.”

Knowing nothing about the events, Marguerite went to the Queen Mother’s quarters, where Catherine discussed something quietly with her ladies. Her mother enjoined her to go to bed and simply sleep, while her sister Claude, who was married to Charles III, Duke de Lorraine, was crying. A suspicious Margot asked again what was going on, but Catherine ordered her to retire for the night. Instead, she visited her husband, in whose chambers Margot found many Huguenots, who were still alive and were hell-bent on demanding justice for Admiral de Coligny the next morning, which most of them did not see. She was awakened when one wounded Huguenot man came to her rooms begging for help, and it seems that it pushed Marguerite to find and hide Henri to save him.

Marguerite described the days following the massacre in her Memoirs:

“Five or six days afterwards, those who were engaged in this plot, considering that it was incomplete whilst the King my husband and the Prince de Conde remained alive, as their design was not only to dispose of the Huguenots, but of the Princes of the blood likewise; and knowing that no attempt could be made on my husband whilst I continued to be his wife, devised a scheme which they suggested to the Queen my mother for divorcing me from him.”

The annulment of Marguerite’s marrriage to Henri did not happen at the time, but their felicity, if they were at least a little happy after the wedding, was shattered into pieces. In the weeks following the massacre, the assassinations in Paris triggered a wave of shocking violence towards the Huguenots across France. From late August to October 1574, the Catholics perpetrated massacres against the Huguenots in many cities including Toulouse, Lyon, Bordeaux, Bourges, Rouen, Mieux, Angers, Orléans, La Charité, Saumur, Gaillac, and Troyes. It has long been debated how many Huguenots perished in Paris and in France in general. According to some estimates, between 3 and 4 thousand men were slaughtered in Paris, with 10-11 thousand nationwide. Some believe that about 30 thousand were murdered in France in total. The Protestant survivors converted to Catholicism for their protection; many fled to Switzerland, England, and Germany.

Simon Goulart, the French and then Genevan pastor, constructed the first narrative of the first three civil wars and of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, in his ‘Mémoires de l’Estat de France’, published in 2 volumes, first in Germany in 1576-77. He described the St. Bartholomew night as one signifying the destruction of culture and humanity, and embodying in itself awful barbarity, as ‘la tragédie des tragédies’ (‘a tragedy of tragedies’). Many Protestant writers were prone to dilate on the virtues of Coligny and other Huguenots in order to glorify their martyrdom, rightfully blaming the Queen Mother and the Guises for the murders. The French Huguenots, who were part of a Reformed family in life, created a sense of community with the past through a psychological link to the early Christianity when martyrdom was the highest possible glory for a true Christian. This concept allowed them to form an organized movement in France and legitimize the Protestant cause by linking themselves to the ancient church. Thus, the martyrdoms of Coligny and the others during the infamous massacre can be found in many works of Protestant pastors and theologians.

However, there was something important from which Admiral de Coligny and his entourage could not be freed. In the beginning of the 1570s, religious wars had been tearing France apart. The First Religious War had lasted from 1562 to 1563, having started with the Massacre of Vassy on the 1st of March 1562. The second Religious War had taken place between 1567 and 1568. The Third War had begun in 1569 and ended in 1570. These early conflicts had all ended with the significant concessions in favor of the Huguenots – the Edict of Saint-Germain of 1562, then the Edict of Amboise of 1563, and finally the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye of 1570, negotiated by the late Queen Jeanne of Navarre and Catherine. The French Huguenots were granted large freedoms and privileges within the Catholic realm, but they wanted more – absolute freedom of worshipping their religion. In the 1570s, it was something that not only the monarchy, but also the predominantly Catholic society were not ready to grant to the Huguenots. Only decades later, when the country would be completely devastated by these wars, Henri IV would be able to give the nation the Edict of Nantes of 1598, aimed to promote civil unity and establish freedoms for the Huguenots.

On the 26th of August, King Charles and Catherine de’ Medici voiced the official version of events: the massacre thwarted a Huguenot plot against the royal family. Actually, some historians believe that the Huguenots could have been guilty of treason. According to some sources, Coligny’s journal of his receipts and expenses, which was presented before the Royal Council and the Estates General, and his other papers confiscated after his death, revealed deeds and projects which would have ensured his execution in any country. In 1563, Duke François de Guise had been about to capture Orléans from Prince de Condé’s troops when he had been stabbed on the 18th of February 1563 by the Huguenot assassin – Jean de Poltrot de Méré. It was rumored that François de Guise was Admiral de Coligny’s victim, which actually made his eldest son and heir, Duke Henri de Guise, yearn for vengeance and could have eventually led to Coligny’s death. However, these documents could have been forgeries manufactured on Catherine’s orders.

According to Pierre de Bourdeille, Seigneur de Brantôme, known as Brantôme (a French historian, soldier, and biographer) and Jean de Monluc (a French noble, clergyman, diplomat, and courtier), many nobles of Charles IX’s court mentioned the young monarch’s fear of Coligny. Nonetheless, Coligny is known to have been a friend of and advisor to Charles, who even influenced the king to consider the French intervention on behalf of the rebelling Spanish Netherlands where the populace consisted of Protestants. In this context, it is interesting to look at the letter of King Charles to Gaspard de Schomberg, his ambassador to the German Protestant States:

“Coligny had more power and was better obeyed by those of the new religion than I was. By the great authority he had usurped over them, he could raise them in arms against me whenever he wished, as indeed he often proved. Recently he ordered the new religionists to meet in arms at Melun, near Fontainebleau, where I was to be at that time, the third of August. He had arrogated so much power to himself that I could not call myself a king, but merely a ruler of part of my dominions. Therefore, since it has pleased God to deliver me from him, I may well thank Him for the just punishment He has inflicted upon the admiral and his accomplices. I could not tolerate him any longer, and I determined to give rein to a justice which was indeed extraordinary, and other than I would have wished, but which was necessary in the case of such a man.”

This letter is taken from Villeroy’s ‘Mémoires Servant a l’Histoire de Notre Temps’. Is it a real letter? Could it have been forged? Perhaps it is true: history is always written by the winners, so Catherine de’ Medici could have ensured sometime after the massacre that Coligny’s reputation was besmirched. Indeed, she was ruthless in her attempts to protect the throne for her sons and the Valois dynasty. Through intimidation and beneficial political marriages, the Queen Mother tried to use her offspring to solve a plenty of political and religious problems in France. Yet, Admiral de Coligny was really a powerful and wealthy Huguenot who posed a threat to Charles IX, especially if thoughts about rebellion against the monarchy, like the Protestants were doing at the time in the Habsburg Netherlands, passed through Coligny’s head. We will never know the truth, but Catherine could have been afraid that her son could be overthrown by Coligny and his armies.

If the above is true, then Charles IX, whose temper and mood were unstable, but who was not a fool, could have perceived that his crown and his life were in imminent danger. Given that the Huguenots always demanded more and more freedoms and privileges, the historical circumstances of the massacre furnish us with the materials sufficient to conclude that the St Bartholomew Night was not only an expression of religious hatred, but could also be a political expediency resorted to by the Queen Mother, her ruling son Charles IX, and his Catholic courtiers for the preservation of his life and throne. The political motive of the massacre was anyway the extermination of the power of the Huguenots regardless of whether Charles’ throne was in peril or not.

The French Wars of Religion awaken conflicting emotions, ranging from shock, sympathy to the Huguenots, and accusations of Catherine de’ Medici and Charles IX. Nevertheless, we do not know the whole truth shrouded by centuries and royal intrigues. Both Catherine and Charles are guilty, together with the radical House of Guise and their supporters, but the Huguenots, glorified as hapless martyrs in Protestant literature, indeed grabbed too much power and failed to appreciate the concessions that the initially more or less neutral Catherine had permitted them to enjoy. There is nothing purely black and nothing purely white: the historical truth usually lies somewhere in the middle. Many Protestant theologians who castigated the massacre exaggerated the number of victims, and at times you can see in their works that more than 50 thousand people were murdered only in Paris, which is impossible just because there could be no more than at most 15 thousand of the Huguenots who had gathered there to attend the wedding between Henri and Marguerite.

The news of the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was welcomed with jubilation in Rome and in Italian duchies and city-states, and in the Catholic Spain. King Philip II of Spain, whose third wife was Elisabeth de Valois (died in 1568), was very vocal about his approval of the policies of the Queen Mother and King Charles IX. In France, the massacre resulted in the Fourth War of Religion, which included Catholic sieges of the cities of Sommières, Sancerre, and La Rochelle. The violence against the Huguenots became increasingly popular, but the French Protestants also attacked the Catholics in the most brutal way. The whole of France was drowning in a crimson ocean, and even the death of King Charles in 1574 did not stop the conflicts.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville