Today is a tragic day: another anniversary of the brutal assassination of Louis I d’Orléans, the second surviving son of King Charles V of France known as the Wise (le Sage) and his consort, Jeanne de Bourbon. Louis was a younger brother to King Charles VI called the Mad (le Fou), who suffered from recurring bouts of insanity throughout most of his adult life. Louis was one of the most powerful and wealthy French peers: he was Duke d’Orléans from 1392 until his death, and he was also Count de Valois, Duke de Touraine, Count de Blois, Count d’Angoulême, as well as Count de Périgord and de Soissons. How could a prince of the blood be assassinated?

History proves that when there is a conflict for power between members of the same royal dynasty or family, everyone might fall prey to a deadly web of intrigues. At the beginning of the 15th century, men close to the House of Valois were fighting for the control of the realm that could not be ruled by the insane Charles VI. The leaders of the House of Orléans (Armagnac faction) and the House of Burgundy (Burgundian faction) had much influence over state affairs in France. The Orléans branch of the family stemmed from Louis I, Duke d’Orléans. The Valois-Burgundy branch originated from Charles V’s younger brother and Louis’ cousin – Philippe the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (he gained his sobriquet after his capture at the Battle of Poitiers of 1356).

The country was controlled by the king’s uncles during his minority, including Philippe the Bold, and later by the monarch’s grown brother, Louis. As long as Philippe was alive, his son and heir – Jean – did not dare pry into politics of France, so despite the friction between Louis and his uncles, no one ever thought of resorting to violence. The Armagnacs and the Burgundians were in conflict over the economic model of France. Louis d’Orléans advocated the traditional French model based on the country’s well-established feudal and religious system with strong agriculture. On the other hand, Philippe the Bold saw advantages of the English model, which made the gentry, cities, and middle classes important for England’s prosperity.

Philippe’s views were highly influenced by his experience of ruling the Duchy of Burgundy. After he had received Burgundy in apanage from his father, he also ruled the prosperous County of Flanders, whose wealth stemmed from trade and was dependent on its economic relations with England. Flanders was the main market for English wool. English cloth merchants determined prices for the wool they sold in Flanders, where local traders and early manufactures (including weavers of famous Flemish tapestries) purchased it to produce end wool products. Thus, Philippe had a different view on the economic model of France, but he of course did not support the English during the Hundred Years’ War.

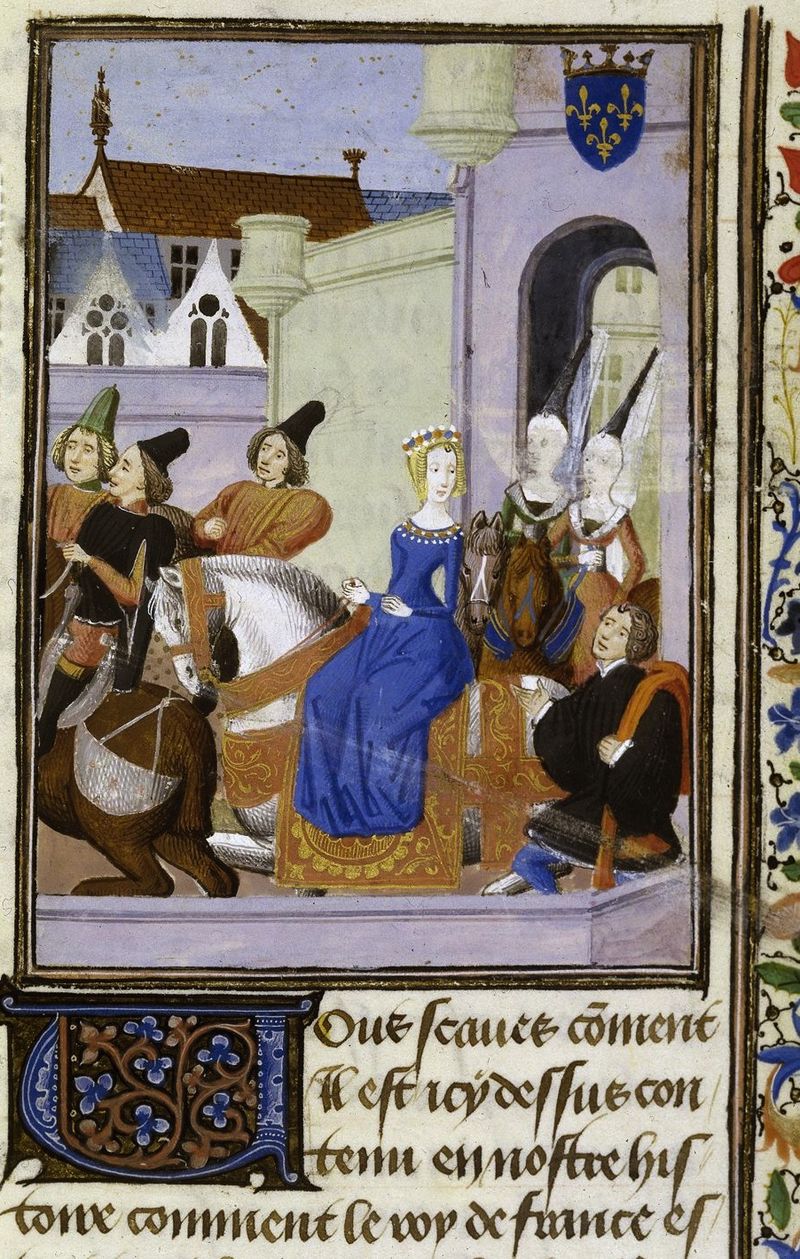

Since 1393, when Charles VI displayed the first signs of insanity, his controversial wife, Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, presided over a regency counsel, but she did not rule France. Isabeau was far more interested in other things: luxurious outfits and jewelry, entertainments, and at times, her brood of children, out of whom her least favorite son was Charles, Count de Ponthieu (later Charles VII of France). At first, Isabeau was highly influenced by Philippe the Bold. Nonetheless, in adulthood Louis d’Orléans obtained influence over Isabeau and was even rumored to be her lover, largely thanks to Louis’ easy-going, licentious lifestyle – he had mistresses despite having the lovely and loyal Valentina Visconti (his first cousin) as his wife. Philippe disliked it, and when Louis acquired Luxembourg in 1402, which the Burgundians considered their private hunting territory, the aging Duke of Burgundy was outraged, but he did not resort to extreme measures.

Philippe the Bold died of natural causes in April 1404. His successor was Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, who had earned the moniker ‘Fearless’ during a crusade he had attempted to lead against the Turks in Nikopol in 1396. Jean was far less refined and more intemperate than his father. The cynical Jean was a practical man, one who disliked that his Orléans cousin received the huge income of 200,000 livres per year, while he got only 37,000 livres. Later, according to the Burgundian propaganda spread by Jean and his descendants, as well as the English, Louis d’Orléans would be named his own grave digger, one who compelled the French people to pay unbearable taxes, who had legions of mistresses and even was the real father of Charles de Ponthieu (Charles VII), and who earned the enmity of his people due to his own faults. In other words, Louis would be publicized as a bad guy, while Jean would be presented as a savior of the nation from the lewd and avaricious Duke d’Orléans. The truth is that Jean was even greedier and more ambitious than Louis was, and definitely far more ruthless than Louis.

According to the Burgundian propaganda, Louis d’Orléans tried to seduce Jean’s wife – Margaret of Bavaria. This might seem true, but to me and many French historians, it looks more like an attempt to blacken the image of Louis already after his demise. The Burgundian faction invented the reason for escalation of the conflict between Jean and Louis. In fact, it was Jean the Fearless who worked hard to foment flames of hatred towards Louis in France by publicly promising the tax cuts and state reforms that would limit the influence of aristocracy and increase that of the Estates General, which represented 3 French classes (estates) – clergy, nobility, and commoners. Indeed, Isabeau increased taxes, much to the populace’s displeasure and at Louis’ behest. But would the greedy and brutal Jean, as history proved it, decrease taxes and give the Estates of General more authority and voice? Of course not, but Jean was a good propagandist.

In 1405, Jean threatened Paris with military occupation, but Louis had his own supporters and the royal army at his disposal. Louis did not take Jean’s threats seriously, and it was his fatal mistake. At one point in the same year, Jean kidnapped Isabeau’s eldest surviving son – at the time Louis, Dauphin de Viennois and Duke de Guyenne. The Duke d’Orléans and his partisans successfully recovered the Dauphin and returned him to Paris to his parents. When you are not capable of committing evil deeds despite your weaknesses like womanizing and avarice which were the faults of most nobles, you cannot imagine what your rival might kill you. As a result, a bitter struggle between Jean and Louis culminated in the murder of Louis. Jean planned his crime in advance: in June 1407, the first enquires were made among property agents in Paris for a house, where the recruited assassins could live until they received a signal from their master.

Jean the Fearless recruited a gang led by the Norman knight Raoul d’Anquetonville. They installed themselves in this house and waited. Between 6 and 7 o’clock in the evening on the 23rd of November 1407, Louis d’Orléans visited Queen Isabeau, his ally at the time, who had birthed her last child about 2 weeks ago – Prince Philippe, who would die at the end of November. It was rumored that the youngest offspring of Isabeau were fathered by Louis, including Charles de Ponthieu and the infant Philippe, but it cannot be proved. The relationship between Louis and Isabeau was affable, and they could have been lovers. Between 7 and 8 o’clock in the evening on the same day, a jovial Louis was ridingon on the rue Vieille du Temple back from the queen’s house with a guard of 10 men, lighting their way with torches. Before he left Isabeau, Louis had been apprised by Jean’s conspirator, Thomas de Courteheuse, that Charles VI urgently awaited him at Hôtel Saint-Paul. Louis was on the way to his brother, not suspecting that his Burgundian cousin had already sent his another conspirator to the assassins’ house. Jean’s plot worked very well.

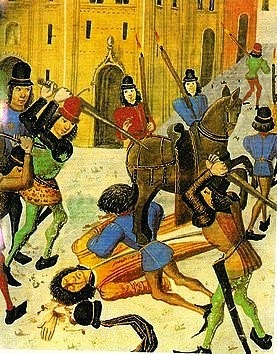

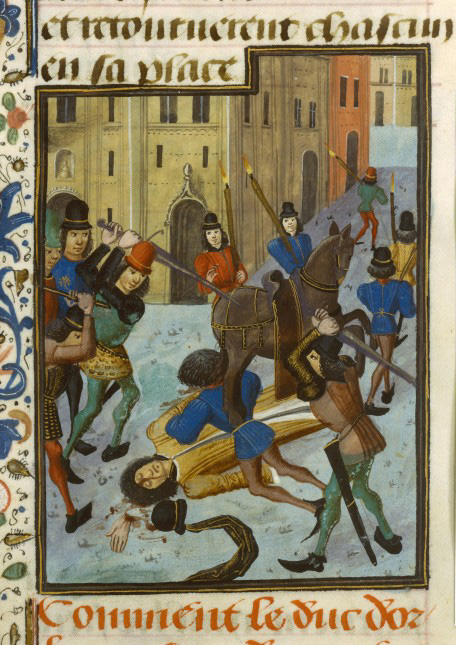

In one of the streets, Louis and his entourage were attacked by 20 masked men. The only witness of this event thought that the merry duke was signing, for she could not distinguish a lot in the darkness from a distance. The woman thought so until she heard the screams:

“Kill him! Kill him!”

Raoul d’Anquetonville and his bandits caught Louis and his men off guard and surrounded them. They lunged with daggers and axes at a shocked Louis, who extended his hand to fend off a blow, but in vain – they literally amputated his arms, leaving him defenseless and unable to unsheathe his sword. His head was cleaved in twain, and Louis’ body was mutilated. Some of the duke’s defendants were butchered, while those who survived were so shaken and frightened that they either could do nothing or feared for their own lives. Perhaps Louis’ surviving guards were petrified by horror as they watched the dreadful slaughter of their master.

According to the woman, the duke’s brains spurted over the road. The men were beating his corpse. Afterwards, a big man, his face concealed by a hood, barked to other thugs:

“Let’s go! He’s dead! Take heart!”

The scattered brains and severed hand of Louis d’Orléans were gathered and put in his coffin with his other remains. In several days after this horrible event, Louis was buried at the Church des Célestins in Paris in the presence of his distraught uncle – Jean, Duke de Berry, and his grief-stricken cousin, Duke Louis II d’Anjou. Louis’ murderer, Jean of Burgundy, was present and was ostentatiously mourning. Later, Louis d’Anjou and his wife, Yolande of Aragon, would become the key Armagnac partisans and supporters of Dauphin Charles (former Charles de Ponthieu). Louis d’Orléans was succeeded by his eldest son – Charles, who would soon watch his mother, Duchess Valentina, succumb to melancholy and some lethal illness, and on whose deathbed he would swear to avenge his father’s murder. Charles’ capture at the Battle of Agincourt of 1415 would result in more than 30 years of his imprisonment in England.

The heinous crime stunned and paralyzed France, and although Louis’ taxes were unpopular, the people of Paris did not wish him dead. Indeed, the speeches and promises of Jean were liked, but nobody could wrap their heads around the fact that a prince of the blood could be so brutally murdered. Not simply assassinated, but butchered in the French capital! As panic seized Paris, an investigation was started by Guillaume de Tignonville, the Provost of Paris. It was not long before suspicion fell upon Jean the Fearless, who soon admitted his crime, much to the horror of his Armagnac relatives and even Queen Isabeau. It is interesting that later, when Jean would dominate the realm’s politics, he would also be suspected of being Isabeau’s lover. The Duke of Burgundy paid to Raoul d’Anquetonville a handsome sum for his “notable services.”

One would expect that the murderer of a king’s brother must always be arrested, prosecuted, and executed. However, Charles VI had rare moments of lucidity, so he was incapable of judging the situation. At last, Jean the Fearless made another Machiavellian move that would make even the Dukes de Guise, who would be responsible for massacres of the Protestants during the Wars of Religion in France in the next century, to blush. Jean declared that the “vile” Louis endeavored to kill the monarch by black magic. Despite the pleas of a disconsolate Valentina Visconti, Louis’ widow, and those of Louis d’Anjou and Jean de Berry, Jean the Fearless’ full pardon was issued. Madness! That would not have been possible if France had not been ruled by the insane king.

Jean’s modern biographer, Richard Vaughan, characterized Jean’s actions:

“One of the most insolent pieces of political chicanery in history.”

The Duke of Burgundy declared the murder of his cousin to be a justifiable act of tyrannicide. It was proclaimed by the theologian Jean Petit, a French theologian and professor in the University of Paris. Even academic minds were bribed by Jean! In contrast to the Burgundian and English propaganda against Louis d’Orléans, the people of France did not approve of Jean’s crime, but they feared the murderer. So, who was a tyrant? Louis d’Orléans, who raised taxes, wanted more lands and ruled France, and to whom women flocked due to his charm and handsomeness? Or Jean the Fearless who killed his cousin, the ruling monarch’s brother, with such indescribable atrocity, and whose promises to the people remained unfulfilled? The answer is obvious.

Jean had Louis assassinated in 1407 to clear the way for his own rise to power. The murder of Louis d’Orléans sparked a bloody civil feud between the Duchy of Burgundy and the Armagnac faction. It would divide France for years until the Treaty of Arras of 1435 between King Charles VII of France and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, would be signed. In the next decade, the unscrupulous and cruel Jean would resort to violence many times, once slaughtering thousands of the Armagnacs in Paris. However, 12 years later, Charles VI’s son and his companions would kill Jean on the bridge at Montereau in September 1419 (read my article about Jean’s assassination: the link is here). Charles VII would always deny that he ordered to dispose of his cousin, but there is little doubt that it was his doing. The Burgundian-Armagnac war was the circle of life and death in the game of thrones; I consider the murder of Jean the Fearless justified.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville