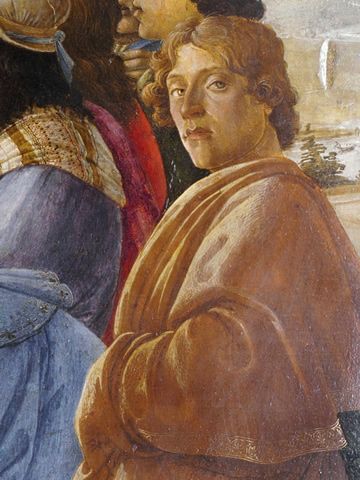

Sandro Botticelli, born as Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, lived at the time when all things intellectual, humanistic, and progressive flourished in the Florentine Republic. The city was truly the cradle of the new era dawning. The artist belonged to the Florentine School under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici Il Magnifico or the Magnificent. His connections with the Medici family helped Sandro’s future successful career as an artist. There is only one probable self-portrait of the great artist, which is part of his ‘Adoration of the Magi’ dated 1475.

Born in Florence, Sandro was the youngest of his father’s four boys to reach adulthood. The year of his birth is believed to be c. 1445. His father was a tanner, and according to Giorgio Vasari, Botticelli was initially trained and worked as a goldsmith with his elder brother, Antonio. The nickname ‘Botticelli’, derived from the Italian ‘botticello’ that means ‘small wine cask’, was obtained from his brother Giovanni, explained by the man’s resemblance to a wine cask. Sandro would be known under this nickname during his whole life and in centuries to come.

At the age of 14, Lady Fortune smiled at Sandro: the teenager became a young apprentice under the guidance of Fra Filippo Lippi. One of the most talented Florentine painters of the time, Lippi enjoyed the patronage of the powerful Medici family – Cosimo de’ Medici the Elder. Thanks to Lippi, Sandro received a full artistic education: a rigorous training in fresco, panel painting, and drawing. Starting from 1462, Sandro created many gorgeous works, most of which were however credited to his master and friend. In the mid-1460s, Sandro worked with Lippi at Prato Cathedral on biblical frescoes. During his entire life, Botticelli’s artistic style and compositions would be somewhat reminiscent of Lippi.

Thanks to Lippi, Sandro became close to the art-loving Medici family. After his teacher’s death in 1469, Sandro’s new independent life as an artist started, and the Medici seem to have aided him to organize his own workshop by 1470. It is interesting that in 1472, the late Lippi’s son, young Filippino Lippi, joined Sadro’s workshop. Fillipino’s work ‘The Adoration of the Kings’ was completed by Sandro. Sandro and his apprentices created many religious paintings, including the popular Madonnas. His pupils tried to imitate Sandro’s style, so it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the works of Botticelli, both Lippies, and his other pupils, in particular in smaller works for private worship.

Sandro was exhilarated when in 1472, he was commissioned to paint two panels from a set of the Seven Virtues to adorn the Tribunal Hall of Piazza della Signoria, one of them being the famous Fortitude that is now on display in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Sandro worked on other panel together with Piero del Pollaiuolo, who unsuccessfully attempted to outshine his fellow artist by using fanciful and whimsical enrichments in the painting. Due to his established contacts with the cultural community of Florence and his friendship with the Medici, Sandro obtained outstanding commissions, one of them the celebrated ‘Primavera’ either for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, or for Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici Il Magnifico, the ruler of Florence.

One of Sandro’s most remarkable works is his painting ‘The Adoration of the Magi’ for Santa Maria Novella, created in 1475-76. This painting showcases the magnificent and pious members of the Medici dynasty. In the scene, Cosimo de’ Medici the Elder is portrayed as the Magus kneeling in front of the Virgin. Cosimo’s son, Piero, is depicted as the second Magus kneeling in the centre with the red mantle, while his second son, Giovanni, is presented as the third Magus. There are also the famed Medici brothers – Cosimo’s grandsons Giuliano and Lorenzo.

At the time of this work’s creation, the three Medici were already dead, and only Cosimo’s grandchildren – Giuliano and Lorenzo – were alive. Young Lorenzo’s bonny face has little resemblance to his later portraits and sculptures, so the painter appears to purposefully have made him more handsome than he was in real life. Now this work can be found in the Uffizi.

In his great encyclopedia ‘Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects’, Vasari describes ‘the Adoration’ in the following way:

“The beauty of the heads in this scene is indescribable, their attitudes all different, some full-face, some in profile, some three-quarters, some bent down, and in various other ways, while the expressions of the attendants, both young and old, are greatly varied, displaying the artist’s perfect mastery of his profession. Sandro further clearly shows the distinction between the suites of each of the kings. It is a marvelous work in color, design and composition.”

In addition to the Medici, the artist had a close relationship with the rich Vespucci family, for example Amerigo Vespucci. In later years, between 1497 and 1504, Amerigo would participate in important voyages during the Age of Discovery, on behalf of Spain and then of Portugal. The Americas were named after this explorer and voyager. There is a legend that Sandro and some other Florentine painters used Amerigo’s superbly attractive cousin-in-law Simonetta, the wife of Marco Vespucci, as the model for their many paintings. Simonetta was viewed as the greatest beauty of her age in Florence, but she died young in 1476 at the age of 22, most likely of consumption.

On the 6th of April 1478, the diabolical Pazzi conspiracy during Mass at the Duomo di Firenze (Florence Cathedral) resulted in the violent death of Giuliano de’ Medici, who was stabbed many times. Nevertheless, the coup d’état failed because Lorenzo Il Magnifico narrowly escaped the assassination. In the aftermath of these horrors, Sandro was tasked by Lorenzo to create a fresco portraying the executions of the leaders of the Pazzi conspiracy by their hanging. According to an old Florentine custom, traitors could not only be killed and/or expelled, their estates and funds confiscated, but they could also be humiliated through the so-called ‘pittura infamante’ – a genre of defamatory painting and relief. Even if Sandro hadn’t wanted to paint the dead bodies, he complied with Lorenzo’s strict orders.

Sandro also worked as a portraitist, although there are few portraits, even of notable people, attributable to him. He painted some, but their number is probably exaggerated by art enthusiasts, for it was not a typical genre for the artist. Most of his portraits are idealized versions of women, which might not represent a specific person because the female sitters on them bear a striking resemblance to the Venus and some of his other works. Perhaps Simonetta Vespucci had indeed been his model for some time before her death. One of Sandro’s portraits is the painting of Giuliano de’ Medici, which might have been created posthumously.

Thanks to his unparalleled talent, Sandro was invited to the papal court in 1481. Although Pope Sixtus IV was an enemy of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Sandro and several other Florentine artists journeyed to Rome. The Botticelli team was tasked to fresco the walls of the newly completed Sistine Chapel. Their contribution in the decoration of the Chapel seems to be Lorenzo’s attempt to establish peace with the Pope, who excommunicated him and who was implicated in the Pazzi villainies. Botticelli’s main frescoes included: ‘the Temptations of Christ’, ‘Youth of Moses’, and ‘Punishment of the Sons of Corah’. Nowadays, the beauty of Sandro’s frescoes is overshadowed by Michelangelo’s later works, especially his stunning ceiling.

Sandro Botticelli returned from Rome in 1482 as a more famous painter. Now he received more handsome commissions for both religious and secular paintings. By the mid-1480s, many illustrious Florentine artists left the city. Together with Domenico Ghirlandaio and Filipino Lippi, Sandro produced a series of marvelous frescoes for Lorenzo’s villa near Volterra. Botticelli also painted many Madonnas and created altarpieces in numerous Florentine churches.

In the 1480s, a spark of Sandro’s interest in mythological subjects led to the creation of two masterpieces. His ‘Primavera’, dated c 1482, appears to have been commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici. This work, which is an icon of Botticelli’s Renaissance genius, depicts a group of figures from classical mythology in a garden – an allegory symbolizing the coming of lush Spring, as well as the springtime renewal of the Florentine Renaissance. From left to right, these figures include Mercury, the Three Graces, Venus, Flora, Chloris, and Zephyrus. Agnolo Ambrogini, known as Poliziano, who was Lorenzo’s close friend, a classical scholar and poet, may have helped Sandro invent the composition.

Botticelli’s another work with emphasis on classical mythology is his majestic ‘The Birth of Venus’, dated c. 1485. The newly born Goddess Venus, completely nude contrary to the traditions of the time, stands in the center of the painting in an enormous scallop shell. The wind God Zephyr is in the air, blowing at Venus from the left. Zephyr carries a young female, who is also blowing. From the right, there is one of the three Hours, Greek minor goddesses of the seasons, who brings for Venus a sumptuous cloak or dress to cover her when she reaches the shore.

Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’ and ‘The Birth of Venus’ are his two most illustrious works, each of them the true icon of the Florentine Renaissance. ‘The Birth’ is better known than ‘The Primavera’ because of the artist’s use of mythology on an unprecedented scale for the first time since classical antiquity. Being both widely admired by art historians, art enthusiasts and collectors , they are both now on display in the Uffizi.

Sandro was not entirely centered on mythology. One of the religious masterpieces he created was the Bardi Altarpiece for the Bardi family in 1485. The frame was manufactured by Giuliano da Sangallo, Lorenzo’s favored architect at the time. On the altarpiece, an enthroned Madonna and the Child sit on an elaborately carved, raised stone bench in a garden, and there is lovely foliage behind them, covering almost the whole sky. This was done to create the illusion of a closed garden, which was a traditional setting for the Virgin Mary.

The untimely death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in 1492 altered the political landscape of Florence. The artist lost his patron and mourned for him, but perhaps not for a long time. Sandro became a devout follower of the moralistic and rather fanatical Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, who preached in Florence from 1490 until his execution in 1498. The friar’s detrimental influence was so profound that Sandro seems to have destroyed some of his paintings on secular themes in the notorious ‘Bonfire of the Vanities’ of 1497, when Savonarola and his supporters gathered thousands of works of art and books, and burned them all.

Vasari wrote about Sandro Botticelli’s life during the 1490s:

“Botticelli was a follower of Savonarola’s, and this was why he gave up painting and then fell into considerable distress as he had no other source of income. None the less, he remained an obstinate member of the sect, becoming one of the piagnoni, the snivellers, as they were called then, and abandoning his work; so finally, as an old man, he found himself so poor that if Lorenzo de’ Medici … and then his friends had not come to his assistance, he would have died of hunger.”

Vasari’s claim that Botticelli’s artistic soul was dead is incorrect. The work ‘The Mystical Nativity’ is dated c. 1500–1501 – Sandro’s only signed work. The Virgin Mary is kneeling before the infant Christ, while shepherds and wise men visit him. It is a scene of celestial happiness, stemming from the presence of the Virgin and Christ, with angels dancing at the top of the painting, and with three angels embracing three men at its bottom. Amusingly, this work remained hidden for another three centuries until it was discovered at the Villa Aldobrandini and was eventually taken to England, where at present it is only display in the National Gallery in London.

Sandro Botticelli never married because he did not desire to have a wife, detesting the entire marriage concept. There has been speculation among art historians, connoisseurs, and writers that the artist could have been homosexual. Some of them observe excessive homoeroticism in his works. According to the Florentine Archives dated 1502, Botticelli kept a boy, which could be interpreted as almost an accusation of sodomy, but there was no prosecution. I think something is wrong with this: as of 1502, Sandro was fifty-eight, and he was not in perfect health.

The Renaissance art historian James Saslow wrote of Botticelli:

“His [Botticelli’s] homoerotic sensibility surfaces mainly in religious works where he imbued such nude young saints as Sebastian with the same androgynous grace and implicit physicality as Donatello’s David.”

According to Vasari, Sandro earned huge commissions during his career, but he squandered them due to his carelessness and money mismanagement. The artist died in 1510 and was interred in the Chapel of the Vespucci family in the Church of Ognissanti in Florence, located close to where he grew up and lived for most of his life. Sandro’s grave is marked by a simple circle of marble, just a few feet away from Simonetta Vespucci. However, the tale that the artist could have suffered from an unrequited love for Simonetta cannot be proved.

All images are in the public domain.

Text © 2020 Olivia Longueville